In Focus: Osterley's lost treasures, brought together more than 70 years after the blaze that split them up

The story of the family that created one of the National Trust’s best-known houses is revealed to Clive Aslet through its collection of art and furniture.

Visitors to Osterley Park cannot usually see the stupendous works of art that, until the Second World War, used to hang there. Stored after Lord Jersey had given the property to the National Trust, many of them were destroyed in a fire in September, 1949. Among the casualties were Rubens’s magnificent equestrian portrait of the Stuart favourite, the 1st Duke of Buckingham, and his ceiling showing his apotheosis.

Speaking to The Times, Lord Jersey thought the losses, which also included a van Dyck, might have cost more than £100,000 — a fraction of what such masterpieces would be worth today. Gone were some of the most glamorous images of a courtier ever produced; gone, too, was the chance of reuniting them with the house from which they came.

In a brilliantly conceived exhibition, the Trust has reassembled what it can of the collection, looking both at the Child family that built the house and the story of its fortune as expressed in the furniture and paintings.

The Childs, like the Hoares of Stourhead, formed one of the great 18th-century banking dynasties. Indeed, they had acquired the Elizabethan house at Osterley as the result of a mortgage default. By the time Francis and Robert Child remodelled it in the early 1760s, employing Robert Adam, who decorated the interior in the neo-Classical style he had brought back from Rome, their tastes were aristocratic. However, as the exhibition shows, earlier generations had lived and collected in a manner more akin to City merchants: rich, even opulent, but reflecting — and not straying far from — the source of their wealth.

In the late 17th century, Francis Child the Elder was a goldsmith. Goldsmiths had begun to realise that they could use the gold that customers left with them for safekeeping to lend money — indeed, more money than the actual value of the gold in their heavy iron strongboxes, in the belief that customers would not want all of it back at once. It was a period of Financial Revolution — of boom and bust.

Unlike earlier financiers, Child managed to navigate the rapids and remain solvent. Having married the daughter of a fellow goldsmith called Wheeler, he eventually inherited the business, which was pursued at the sign of the Marygold at Temple Bar. An early cheque was written by a son of the Duke and Duchess of Beau-fort: ‘Pray do me the favour to pay this bird-man four guineas for a paire of parckeets [sic] that I had of him. Pray dont let any body either my Ld. or Lady know that you did it and I will be sure my self to pay you honestly againe.’ There was money for Child to make from noble extravagance.

With William II and Queen Mary on his books, as well as Sir Isaac Newton and Nell Gwynne, Child — soon to become Sir Francis — was elected Lord Mayor of London in 1698. We can see the silver dish given to him by the Jews of the City’s Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue to mark the occasion. Osterley still has some of the porcelain and lacquer, emblazoned with the coat-of-arms Sir Francis was granted in 1700, which the family acquired through their prominent role in the East India Company. Both he and his son, Sir Robert, invested heavily in the South Sea Company, but came out on the right side of the Bubble.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Sir Robert was the Maecenas of the family. By 1702, he had bought a house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where he displayed his many treasures, including the paintings destroyed in the fire of 1949. Although, according to the art critic Bainbrigg Buckeridge in 1707, the ‘English Nobility and Gentry’ kept their collections behind closed doors, Sir Robert created his ‘as much for the publick Instruction, as for private Satisfaction’.

An alderman like his father, he remained a London figure. A flavour of his collection is given by Carlo Dolci’s Saint Agatha — a superb technical achievement, if not wholly to modern taste — and the self-portrait by William Dobson, artist of the Cavalier court: an answer to the van Dyck newly acquired by the National Portrait Gallery.

This thoughtful show, which celebrates 70 years of the Trust at Osterley, should be encouraging to members who fear the Trust has given up on the serious study of country houses. A particularly welcome development is that much of it has been made available on its collections site www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk.

'Treasures of Osterley — Rise of a Banking Family' is at Osterley Park and House, Isle-worth, Middlesex, until February 23 call 020–8232 5050 or see www.nationaltrust.org.uk/osterley

In Focus: The masterpiece painted in Cornwall by an iconic Finnish artist

Helen Schjerfbeck is a national icon in Finland but hasn't had a solo exhibition in Britain since the 19th century.

Credit: Alamy

In Focus: A grim masterpiece of the French painter who became the ultimate storyteller in paint

Laura Freeman examines the brilliance and bravado of Eugène Delacroix’s paintings – including an extraordinary recreation of one of the most

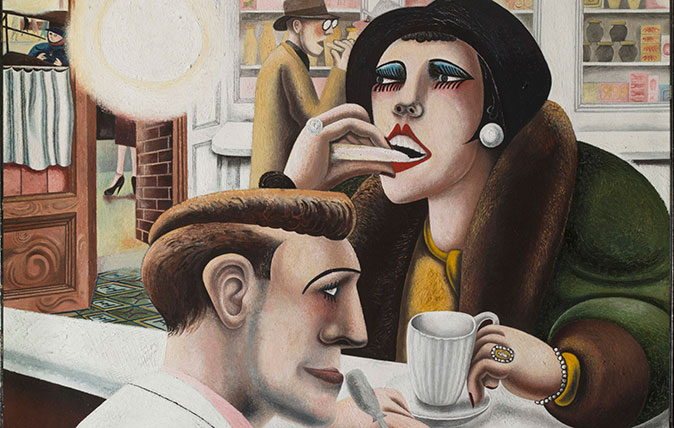

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

Credit: © Musée Rodin

In Focus: Rodin's quirky take on one of the treasures of the Elgin Marbles

-

Athena: We need to get serious about saving our museums

Athena: We need to get serious about saving our museumsThe government announced that museums ‘can now apply for £20 million of funding to invest in their future’ last week. But will this be enough?

By Country Life

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel