In Focus: The Norman Ackroyd landscape etchings that have sparked comparisons with Turner

This week marks the last chance to see Norman Ackroyd's sublime exhibition in Richmond. Lilias Wigan urges you to take the chance to enjoy the work of one of our greatest living artists.

Coinciding with the artist’s 80th birthday, Norman Ackroyd’s Travels with Copper and Wax (until May 26th at One Paved Court, Richmond, Surrey) mounts two distinct bodies of monochrome etching work that span almost 30 years. A series of ‘intimate English landscapes’ from the early 1990s is presented next to ‘the edge’ – dramatic views of Scottish and Irish coastlines.

It was expected that Ackroyd – the son of a butcher – would take over the family business in Leeds; making art for a living was not taken seriously by his household. Encouraged by a school teacher who gave him the keys to the art materials cupboard, he pursued his artistic motivations. First attending Leeds College of Art and then the Royal College of Art in London, he completed his studies in 1964, a time when Pop art was the prevailing style.

Ackroyd, though, was always excited by landscape. Unafraid to battle the elements, he journeyed to remote parts of the U.K. and Ireland, often chartering boats from local fishermen to reach the wild and craggy outposts of the Northern Isles and the Celtic archipelago.

Unusually for a landscape artist, Ackroyd's interest in rural areas lies primarily in the human presence, or 'traces of habitation' of a place. Among locations that have most aroused his imagination is the group of islands that make up St Kilda, the remotest part of the British Isles. The last native St. Kildans were evacuated in 1930, and remains of their dwellings and other evidence of their rich history lie scattered across the islands. A group of etchings on show here was made after Ackroyd returned to St Kilda in 2010, derived from sketches done in situ on a fisherman’s boat.

In Boreray and the Stacs (at the top of the page), a monolith of rock obtrudes with sculptural solidity from a swelling sea. It stands ecclesiastical against shadows of mysterious geological forms, veiled by lashings of smoky rain. A squabble of flighty gulls swoops and dives impulsively, scattering the scene.

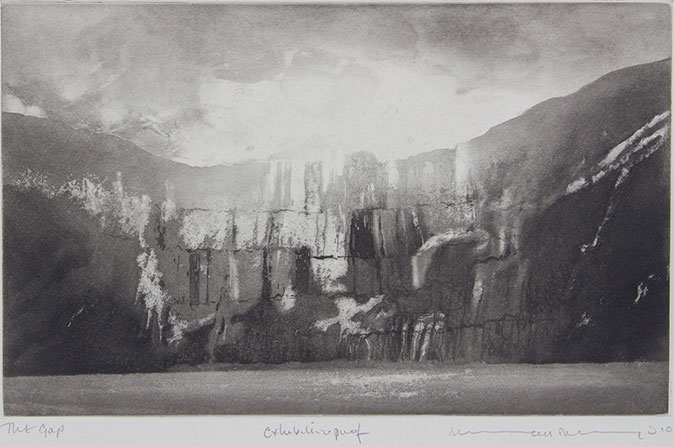

His depiction of a cliff face in The Gap pushes abstraction further; celestial light breathes through rainclouds, highlighting jagged rock formations with lyrical fluidity.

Ackroyd’s subtle abstractions of every scene, combined with his dramatic tonality, heighten our awareness of his sensory experience of each place. His aesthetic vision and spontaneity with his medium have drawn comparisons with Turner, whose works, like Ackroyd’s, capture something of the Sublime.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Norman Ackroyd's etching process

Ackroyd lives above his ‘etching factory’ in a converted leather warehouse in Bermondsey. Here, he has spent most of his artistic career working with aquatint, an 18th century intaglio printmaking technique designed for creating areas of tone. He refers to this medium as ‘engraving with acid’. During the process, a layer of finely powdered (acid-resistant) pine rosin – the same resin that is used to rub into the bows of stringed instruments – is evenly layered onto the copper etching plate. It is then activated using heat and bathed in acid, which dissolves the metal around the rosin particles, enabling ink to leak into the sunken areas.

The black ink Ackroyd uses is derived from burning natural materials, such as bone, vine leaves or peach stones, and sometimes mixed with carmine pigment for elasticity and softness. When printed, the dissolved areas allow for tonal complexities unachievable with other engraving etching techniques. Such gentle gradations of tone are achieved by allowing the acid to eat into the metal for varying lengths of time, making it easy to over-etch and ruin the image.

- Norman Ackroyd’s exhibition ‘Travels with Copper and Wax’, is at One Paved Court, Richmond, until May 26th. Entry is free. See the One Paved Court website for further information.

Credit: Bridgeman

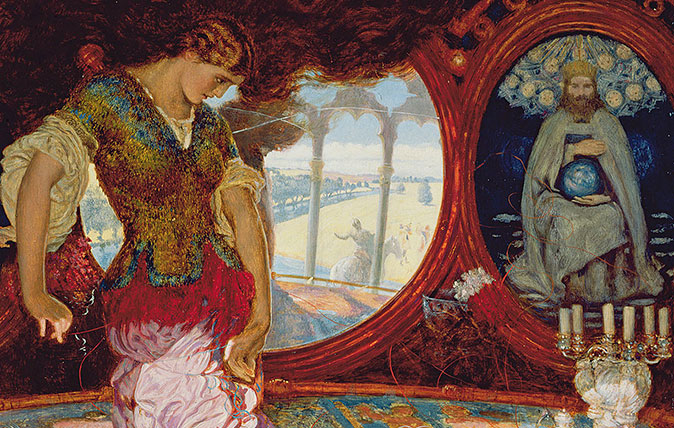

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

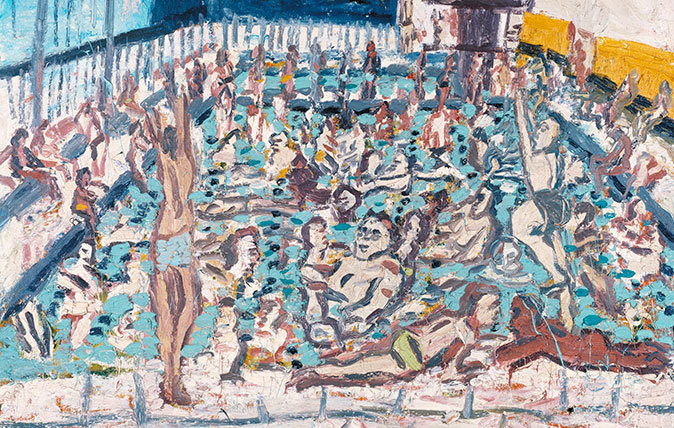

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show