In Focus: The mesmerising work of Anni Albers, the Bauhaus graduate who turned weaving into fine art

Anni Albers' extraordinary talent for weaving elevated her craft to the very highest levels. Chloe-Jane Good takes a look at one of her most famous pieces, 'Black, White, Yellow', which is part of a new exhibition of her work at the Tate Modern.

Tate Modern’s exhibition dedicated to the work of Anni Albers (1899–1994) is a refreshing look at weaving as an art form equal and intrinsic to drawing, painting and sculpture. It is the first major retrospective of the work of Albers in the UK and it coincides with 2019's centenary of the Bauhaus art school, where the artist as student first came to weaving.

The exhibition chronicles a life’s work rich in colour, form, pattern and material. There are early small-scale studies on paper – some realised as woven textiles, some not – wall hangings and floor coverings. There are hangings with two sides to be walked around, jewellery constructed of everyday functional objects and prints. And then there is a selection of pre-Columbian artefacts that she and her husband, Josef Albers (1888–1976), collected on their frequent travels to Mexico, Peru and Chile.

In 1922 Albers – then Annelise Fleischmann – entered the Bauhaus art school in Weimar, Germany, and enrolled in the weaving department, as did many of her female peers. Despite the egalitarian principles on which the institution had been founded three years previously, women were encouraged to join the weaving workshop and discouraged from other disciplines like painting and drawing. That pressure worked in her favour, for it was in weaving that Albers unexpectedly found her mode of expression in a context of modernism and modernist architecture. She would continue to weave for most of her career.

She stayed at the Bauhaus and became a teacher there with her husband until 1933 when they emigrated to the U.S.A to escape the rise of Nazism. She and Josef went on to teach at the experimental Black Mountain College in rural North Carolina where they stayed until 1949.

It was in the aftermath of the First World War that the radical Bauhaus emerged to synthesise art and design – fine art, craft, architecture, graphic design – with industry, mass production and function. The founder, Walter Gropius, was inspired by 19th century English designer William Morris, who believed in marrying form and function and smashing established hierarchies in artistic practice where fine art was seen as superior to craft.

The architecture of the Bauhaus style, also known as The International Style, includes the Bauhaus school building in Dessau, designed by Gropius himself, where Albers studied. The design is characterised by simplicity of form and rejection of ornamentation; by flat planes, neutral tones, spaciousness, lightweight materials which are mass produced and uniform, repetition, straight lines and large areas of factory-like windows (some of which mechanically open and close) with slim black frames contrasting to white walls.

It was in this context that Albers learned about standardisation, reduction of form, structure and colour. In her woven textile Black, White, Yellow (made in 1926, but re-woven in 1965), now on show at Tate, three colours produce surprising variations of tone within a restricted palette by alternating yarn combinations in weft and warp.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The pattern comprised only of rectangles, horizontal and vertical, is repetitive and structured but light and with movement as the pattern system is not clearly locked down. The horizontal black lines, vertical yellow and white rectangles, lightweight yarns and the flatness of the object, though textural, mimic the walls and windows of the Dessau building.

In Black, White, Yellow the rhythms of the geometric lights and darks are like openings and closings, pushing and pulling. They evoke sounds and activity of the Bauhaus years and industry of the time - pressing and releasing of typewriter keys, mechanical opening and closing of windows at Dessau and an action repeated on a factory production line.

In her book On Weaving (1965) Albers illustrates undated studies she made on a typewriter by repeating in lines up to three different characters to make ‘tactile-textile illusions’. The results are beautiful woven compositions, which are mechanical but abstract and delicate. Subtle fluctuations in thickness of ink caused by the varying pressure applied to the keys by the human hand show us that this is a collaboration of craft, machine and function with textual language as the tool.

Black White Yellow is an early experiment in abstract language, typography and graphic design, which Albers produced while studying at the Bauhaus. It is significant that László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) from 1923 co-taught the Bauhaus foundation course with Josef Albers and was a pioneer in subverting conventional 'grey' presentations of textual language by thinking of it in terms of visual form as much as a language of semantics. He organised bodies of text into blocks in relation to illustrations and the page and introduced other typographical elements such as lines and squares like Albers’ typewriter studies and Black White Yellow.

Indeed the word ‘text’ is derived from the Latin word ‘textus’ meaning ‘woven’. Albers was fascinated by ancient language systems and described in On Weaving how in civilisations such as ancient Peru, where there was no written language, woven textiles along with cave paintings were crucial and powerful methods of communication.

Anni Albers at Tate Modern runs until January 27 – see more details here.

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

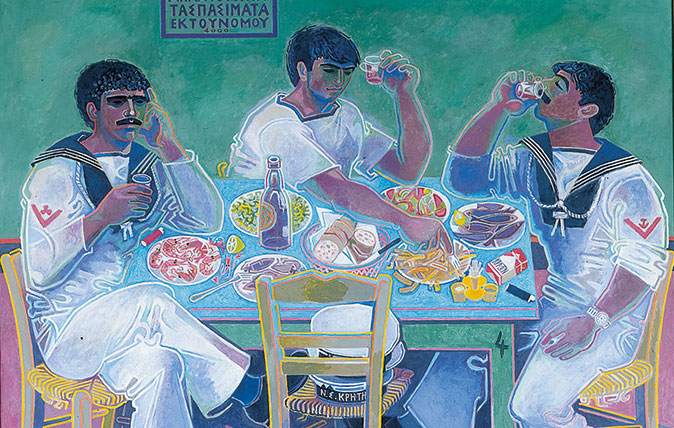

In Focus: The charmed life of Paddy Leigh Fermor and friends in Greece

The iconic writer Paddy Leigh Fermor and two of his friends in Greece – both artists, one a local man and

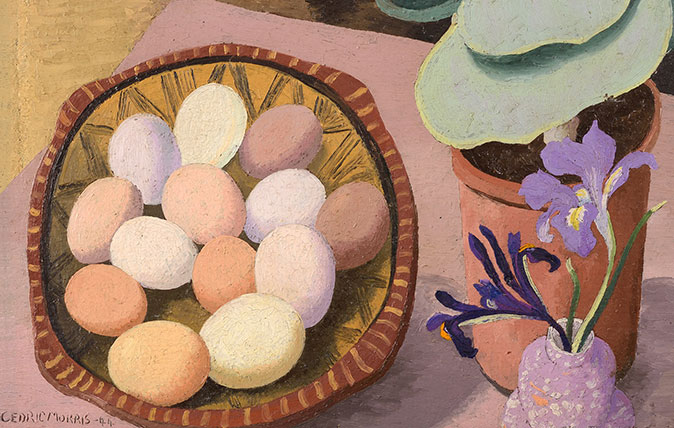

In Focus: The plantsman-turned-artist who found art in flowers, and painted from corner to corner

Cedric Morris's striking still life images have been largely forgotten for three decades, but three new shows are ending that

In Focus: A moment in time capturing the gulf between architects' dreams and residents' realities

Tony Ray-Jones was one of a generation of photographers who chronicled life in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s, demonstrating

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher