In Focus: The 'jobbing artist' who pioneered new technology and defined countryside painting as we know it

The landscape artist Paul Sandby divided critics even within his own lifetime, but what he left behind is an honest and lively portrayal of rural life in 19th century Britain. Huon Mallalieu takes a look at this unusual artist after visiting a new exhibition at Newstead Abbey.

In his Royal Academy lecture on ‘Invention’, which was published in 1810, Henry Fuseli damned many landscapes as being no more than the ‘tame delineation of a given spot; an enumeration of hill and dale, clumps of trees, shrubs, water, meadow, cottages and houses’, amounting to ‘little more than topography… [a] kind of map-work’.

Even if this was not intended as an attack on Paul Sandby – the watercolour painter and senior academician who had died the previous year, and who is celebrated in a new exhibition at Newstead Abbey – it might as well have been.

Sandby was, indeed, a superb topographer; at the outset of his career, he had been a map-maker and, throughout much of it, he taught military officers and the families of his patrons to record what they saw. However, other than officers working in the line of duty, they were also taught to view the prospects before them in terms of poetry and harmony.

More admiring critics in about 1800 had praised Sandby as the artist ‘who, by his works, familiarised us with our own scenery’ and noted: ‘From the frequent contemplation of this variety of scenery, a variety with which Great Britain abounds, he has formed a style peculiarly English, and, among the artists and amateurs of this country, deservedly holds a high character for taste and talent.’

Gainsborough, himself a master of ‘invention’, acknowledged that if ‘real Views from Nature in this Country’ was what you required, then Sandby was your man.

Sandby was born in Nottingham in 1731. On the death of his father, a framework knitter, in 1742, he went to London with his elder brother Thomas, who was appointed a draughtsman to the Board of Ordnance at the Tower of London. Paul followed the same path and was sent to Scotland as a draughtsman on the post-Jacobite survey of the Highlands, remaining there from 1747 to 1751. This vital training enabled him to attract patrons on his return to the South, as portraits of houses and estates, together with their antiquities and picturesque scenery, were very much in demand.

Unlike Thomas’s watercolours, which exemplify his principal concerns as an architect and landscape designer, Paul’s work is full of animation. He often added figures to enliven Thomas’s scenes.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Paul was very much a jobbing artist, painting murals and theatre sets, publishing satirical political prints and taking a great interest both in painting materials and methods and in print-making, especially technological innovations that could help him popularise and sell his work.

He has sometimes been credited with the invention of aquatint, a method that gives great depth and texture, although, in fact, it had been pioneered by J. B. Le Prince in France and was passed to Sandby by his patrons, the Greville family. However, he named it, managed to maintain a near monopoly in Britain and used the method most effectively.

From 1768, Paul was the drawing master at the Woolwich Military Academy and, in the summers, he would generally tour the country with patrons or pupils. He made three Welsh tours in the early 1770s, working for Sir Watkin Williams Wynn in the north and Sir Joseph Banks in the south, and Welsh scenery became a major component of his exhibited and published work. Eventually, there were four sets of Welsh aquatints, which had a strong influence on both amateur and professional artists for the remainder of the century.

The Sandby brothers were closely connected to Windsor, where Thomas was Deputy Ranger of the Great Park, and Paul frequently painted the Castle and its environs. George III never bought one, but, thanks to George IV and the present Queen, the Royal Collection is now rich in Sandby watercolours, drawings and occasional paintings.

So, too, is the Nottingham City Museums Collection, which inspired the current exhibition at Newstead Abbey, ‘Harmonising Landscapes; the work of Paul Sandby RA’. The works selected provide an excellent introduction to his career, including topographical work and capriccios and giving due prominence to the prints. Sometimes, the original drawings are shown with the prints; surprisingly, the process does not seem to have required them to be reversed.

Among the exhibits are views of Nottingham Castle and Lord Byron’s Newstead Abbey itself; particular pleasures include two enchanting gouaches of the Sandby family at Englefield Green and a view of the studio at the end of Sandby’s London garden.

‘Harmonising Landscapes; the work of Paul Sandby RA’ is at Newstead Abbey, Ravenshead, Nottinghamshire, until January 6, 2019 – see www.newsteadabbey.org.uk for more details.

Credit: John Spencer-Churchill's <i>Dunkirk from the Bray Dunes, May 29, 1940</i>. Image courtesy of Andrew Sim / www.simfineart.com

In Focus: The painting by Churchill's nephew that gives a unique view of the evacuation of Dunkirk

A unique painting of the evacuation of Dunkirk by Winston Churchill's nephew was recently unearthed. Huon Mallalieu takes a look

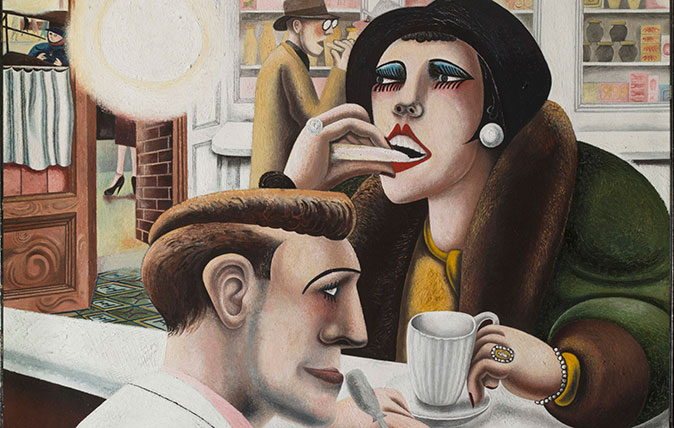

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

Credit: Getty

In Focus: The hand-drawn maps from which JRR Tolkien launched Middle-earth

'I wisely started with a map and made the story fit,' JRR Tolkien once wrote. A new exhibition in Oxford

The Mary Rose museum review: Prepare to be moved and impressed

Huon Mallalieu re-visits the Mary Rose museum in Portsmouth for the first time since its refurbishment – and suggests we all

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to Cairo

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to CairoWhy do we travel and who inspires us to do so? Chris Wallace went in search of answers on his own epic journey the length of Africa.

By Christopher Wallace

-

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River Tay

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River TayCarnliath on the edge of Strathtay is a delightful family home set in sensational scenery.

By James Fisher