In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show at the Tate's latest exhibition of post-war British art.

All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life at Tate Britain celebrates post-war British figurative painting. Almost 100 works are gathered here, including two rarely exhibited portraits by Francis Bacon, a little-known portrait of Lucian Freud (with whom he had a turbulent relationship) and a 1962 portrait of Bacon’s lover Peter Lacy, who grimaces from a chair with his internal organs revealed in lurid detail.

The essence of the exhibition is the so-called ‘School of London’, the group of artists who, in the mid-1970s, pursued various forms of figurative painting at a time when artistic trends favoured abstraction. A key example is the Michael Andrews’s tender picture Melanie and Me Swimming (1971), in which he explores the father-daughter relationship.

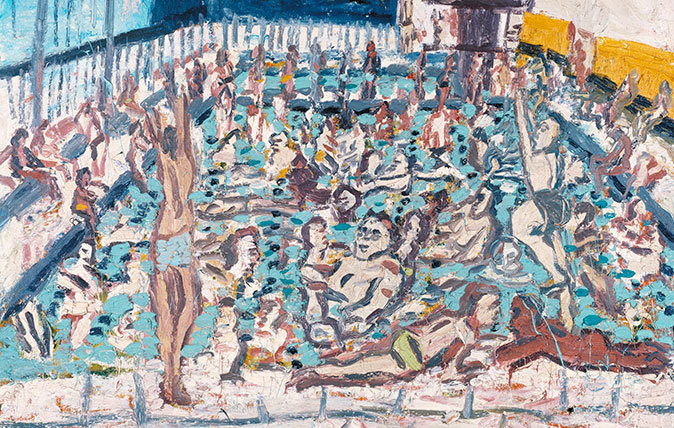

The image on this page is on a similar theme. Leon Kossoff’s Children’s Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon (1971) recalls trips made with his children to a pool near his studio in Willesden Green in London. Sitting watching them from the cafeteria, Kossoff drew numerous sketches, from which he created five large-scale oil paintings. The figures in the drawings tend to be anonymous, but when he painted them they acquired characteristics of people close to him.

"His use of a Titanium White ground colour gives the light a glow, carrying with it a sense of his determination to preserve childhood memory."

Unusually for Kossoff, the paint is applied relatively thinly and evenly distributed across the crowded canvas. Equal importance is given to the architecture — he even picks out the lane divisions with bold dabs of colour — as to the figures and their patterns of behaviour. ‘I was very interested in how the pool changed during the summer months and how at different times of day the changing of the light and rise and fall of the changing of the volume of sound seemed to correspond with changes in myself,’ he later wrote.

The result of this prolonged observation is one of brilliant energy and movement. An atmospheric buzz emanates from the brushstrokes, evoking the clamour of children playing. His use of a Titanium White ground colour gives the light a glow, carrying with it a sense of his determination to preserve childhood memory. Kossoff reminisced about this period as one of the happiest in his life.

By incorporating influences from the turn of the 20th century as well as developments in current figurative painting, the exhibition covers a vast period and variation of approaches. It exposes the differences and contradictions between these figurative artists as much as it argues their similarities.

- All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life is at Tate Britain in London until 27th August, 2018. Find out more at the Tate website.

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

In Focus: Cézanne's brutally honest portrait of his wife, 'weary and dissatisfied', as their relationship was on the rocks

The National Portrait Gallery's exhibition of portraits by Paul Cézanne comes to an end this weekend. Lilias Wigan takes an

Credit: Bridgeman

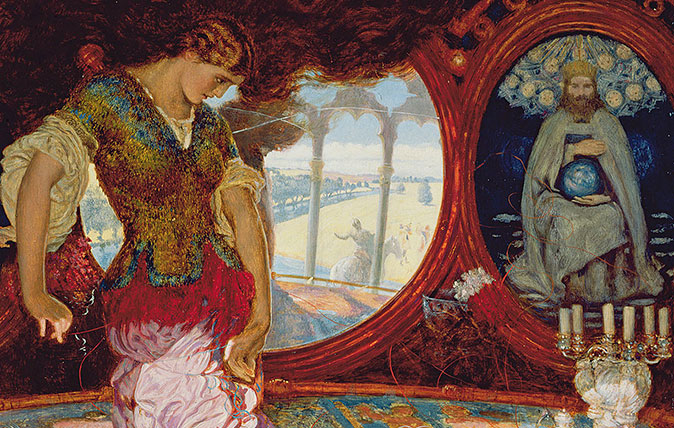

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

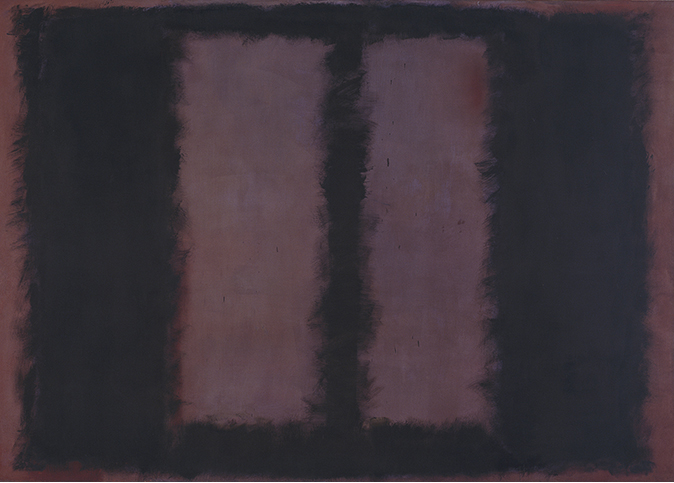

My favourite painting: Ann Christopher

'I do remember being moved to tears—not in a depressive way, but with powerful emotion'

My favourite painting: Robert Macfarlane

Robert Macfarlane chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

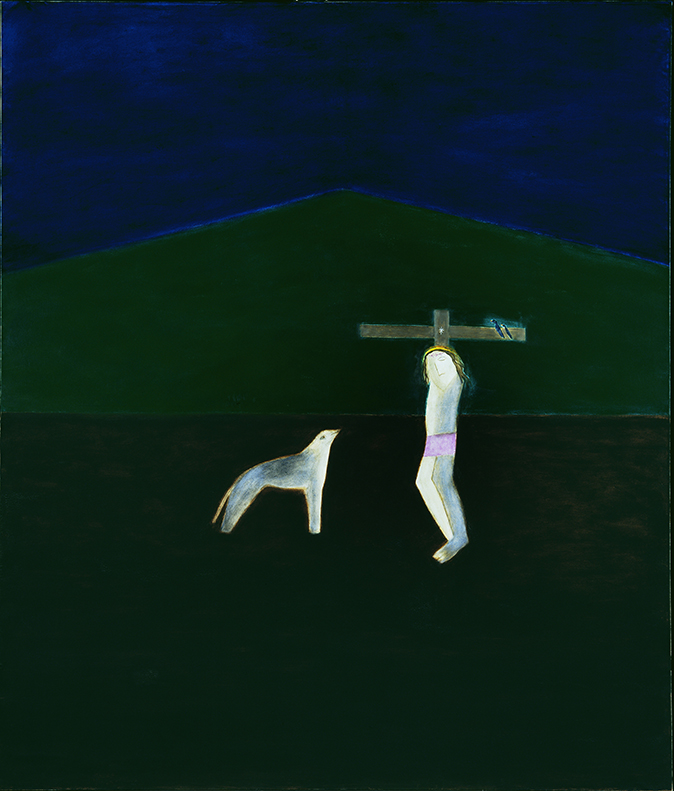

My favourite painting: The Bishop of Gloucester

'The simplicity and mystery resonates with my faith'

My favourite painting: Grey Gowrie

'The result was this balletic joy, as if Matisse had gone to work on a lavatory wall.'