In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at the painting, which is part of a new exhibition at the National Gallery.

Sometimes, a single artist can inspire an entirely new movement. And sometimes it only takes one picture.

Such was the case with Jan Van Eyck’s painstakingly detailed The Arnolfini Portrait (1434), acquired by The National Gallery in 1842, and the inspiration behind the gallery's new exhibition, Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites.

The artist’s use of the reflective convex mirror in this picture drew particular fascination among the Pre-Raphaelites, affirming his unprecedented skill as a painter and offering many possibilities for interpretation. All this coincided with the invention of photography and a new appreciation of realism and sharp focus.

By 1848, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, three aspiring students at the Royal Academy Schools (which then shared a building with the National Gallery), had become disenchanted with the sterile teachings of High Renaissance art. They wanted to express ‘genuine ideas’ and to ‘sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art’, and so they founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and developed what at the time was considered a radical artistic movement.

Favouring the work of Italian and Netherlandish artists ‘pre-Raphael’, they found that The Arnolfini Portrait upheld many of their artistic ambitions. This exhibition explores the influence of Van Eyck’s portrait on their work, and how they used reflection as a device to develop their objectives.

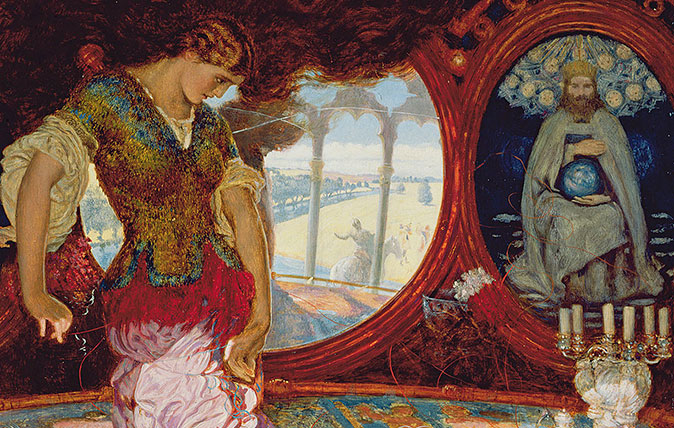

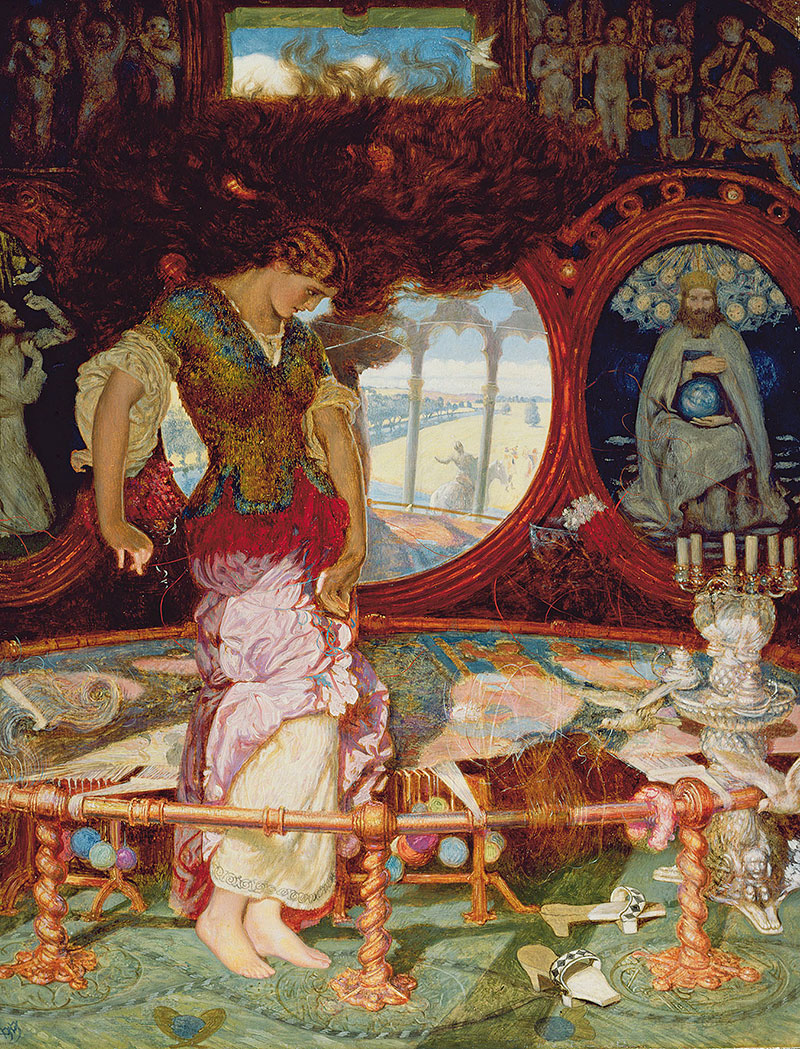

Drawn to themes from religion, literature and medieval legend, the Pre-Raphaelites were particularly taken by The Lady of Shallot. Holman Hunt was the most deeply inspired by the tale's psychological drama. In his painting of c.1886–1905 (below), lent by Manchester Art Gallery, he captures the very moment the Lady catches sight of Lancelot’s reflection, which ultimately leads to her demise.

The convex mirror — the key motif borrowed by the Pre-Raphaelites from Van Eyck — plays a pivotal role. It cracks suddenly and the weaving threads wrap round her twisted body.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The detailing of the discarded candelabra and slippers — objects also borrowed directly from The Arnolfini Portrait — parallels the popular interest that was evolving in photographic observation. A series of small daguerreotypes on display, dating from the 1840s-50s, shows the extent to which extraordinary precision, then becoming so fashionable, could be achieved.

The legacy of Van Eyck’s highly sophisticated painting went beyond the Pre-Raphaelites to inspire artists well into the twentieth century, examples of which are hung in the final room. This exhibition offers a refreshing opportunity to see a familiar painting in new surroundings and in the wider context of its significance to Western art.

Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites is on at the National Gallery in London until April 2, 2018

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

Credit: Michael Armitage, The Flaying of Marsyas, 2017. © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby). Courtesy of the Artist and White Cube.

In Focus: Michael Armitage's image of African violence that points the finger back at the western world

Michael Armitage's The Flaying of Marsyas is the centrepiece of his exhibition in South London. Lilias Wigan examines it in

In Focus: Cézanne's brutally honest portrait of his wife, 'weary and dissatisfied', as their relationship was on the rocks

The National Portrait Gallery's exhibition of portraits by Paul Cézanne comes to an end this weekend. Lilias Wigan takes an