In Focus: Henry and John Crealock, the Victorian military brothers who turned their hands to art

Huon Mallalieu considers the careers of Henry Hope Crealock and John North Crealock, the Victorian army officers and sometime-artists whose careers saw them come into contact with one of Britain's most famous military figures of the 19th century: Field Marshal Wolseley.

Field Marshal Sir Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount and Commander-in-Chief of the army, was one of the most famous British military commanders of the 19th century. He was famously efficient — the military expression ‘all Sir Garnet’ means ‘all in order — but he was also a snob. Or, more accurately, a double snob.

Although from a distinguished Anglo-Irish family, his beginnings were impoverished, as his widowed mother and six siblings had only a major’s pension to support them. He had to leave school at 14 and could not afford to go to Sandhurst or to buy a commission, but he did eventually gain an ensignship and flourished in the army. This may have coloured his attitude to some of his colleagues.

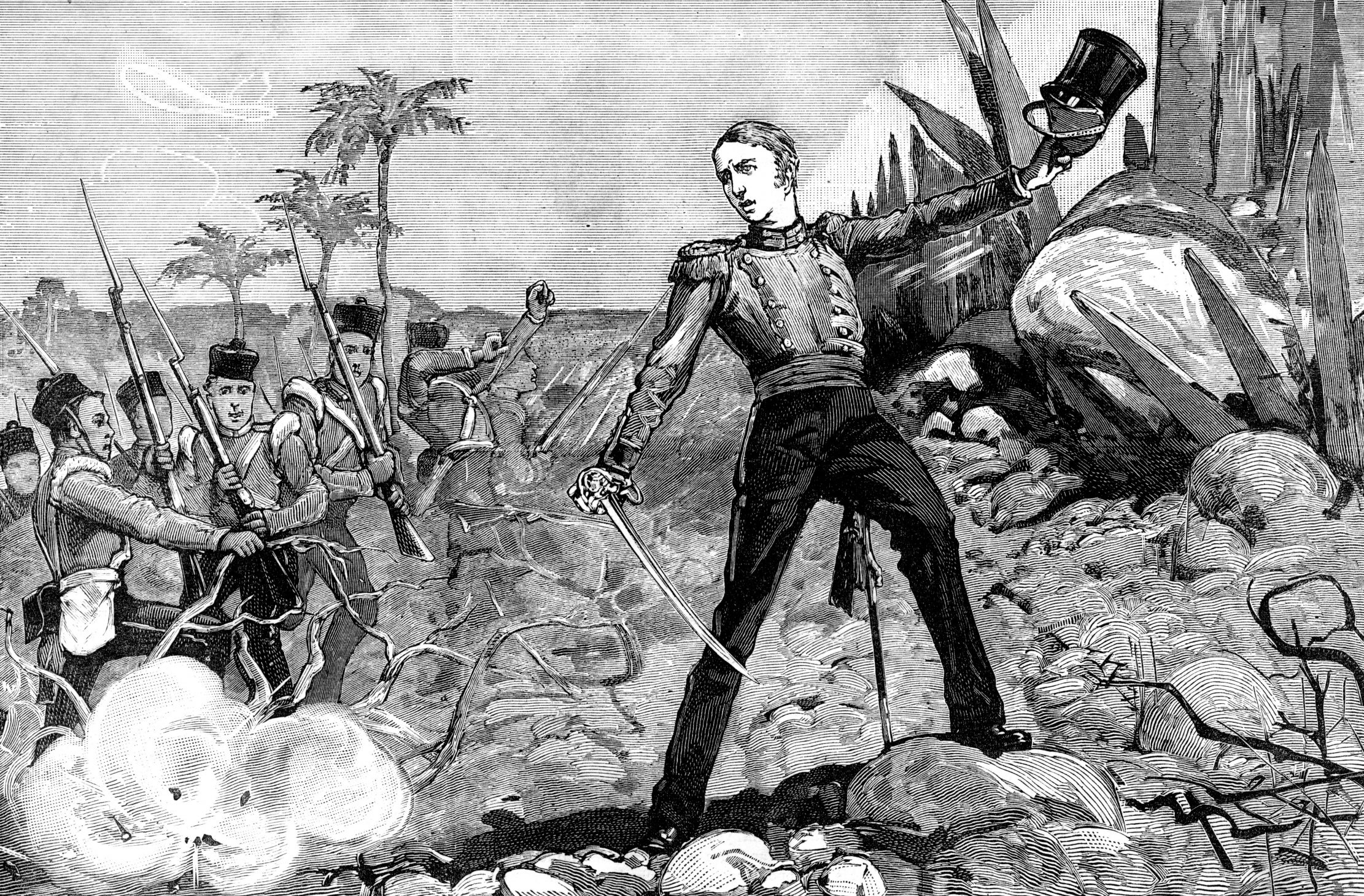

During the final operations of the Indian Mutiny, he served alongside the future Lt-Gen Henry Hope Crealock (1831–91) and, later, during the Zulu War, he also crossed paths with Crealock’s younger brother, Military Assistant to Lord Chelmsford. Chelmsford was the commander responsible for the disastrous slaughter at Isandlwana.

John North Crealock was first on the scene the day after that battle and his illustrated account appeared in the London press. Later, he lied in court, trying to shift the blame from his chief. Wolseley regarded him as ‘Chelmsford’s evil genius’ and, in a private letter, wrote that the brothers ‘are both snobs, and as they were not born gentlemen they cannot help it’. Surely a case of it takes one to know one.

The brothers were both competent amateur artists and, at one point, Henry Hope left the army in an attempt to earn a living as a painter in Rome. In fact, he was more draughtsman than painter and albums of his hunting and shooting sketches turn up in country houses from time to time. One large group, including a couple of atmospheric pastels, was sold for £37,500 by Bonhams in Edinburgh in 2016.

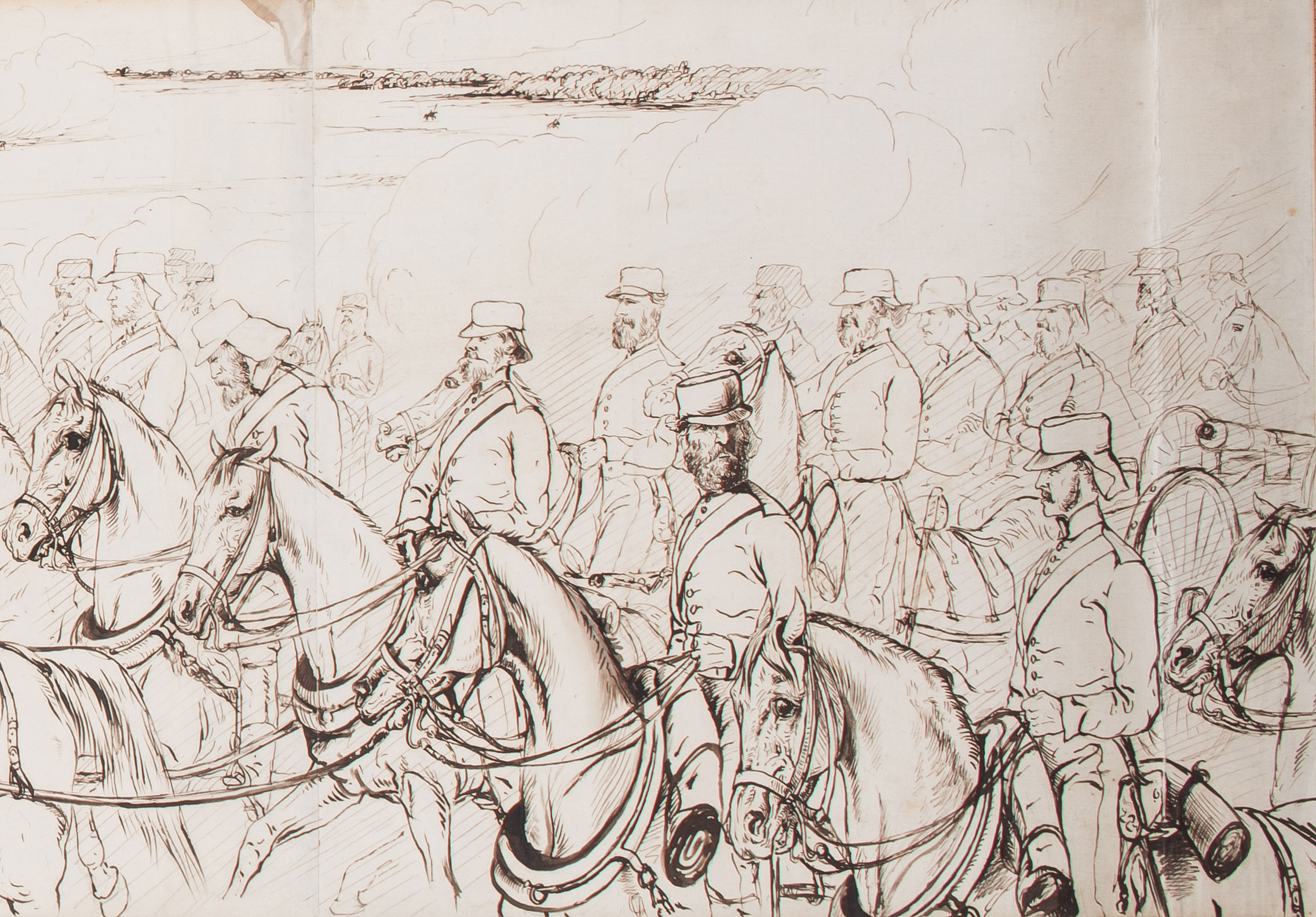

Last month, in a picture sale at the re-designated Olympia Auctions in west London, a 13in by 80in pen-and-ink panorama by him sold for £11,700 to South Lanarkshire Leisure and Culture, The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) Collection-Low Parks Museum, South Lanarkshire, with the support of the Army Museums Ogilby Trust.

It showed the situation of the British force under Sir Colin Campbell on May 5, 1858, as it advanced on Bareilly in what is now Uttar Pradesh, stronghold of Khan Bahadur Khan Rohilla, one of the last rebel leaders, who had declared himself Nawab and was later captured and hanged.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In the extensive inscription, Crealock noted that he had represented himself going ahead ‘taking the order from General Mansfield, who is pointing out the direction of the spot to be fired on’. He has named officers, but not Wolseley.

In Focus: The war artist who taught Hockney, and whose reputation is only going to grow

In Focus: The story behind the London Mastaba, the 7,506 barrels currently floating on The Serpentine in central London

The artistic husband-and-wife team of Christo and Jeanne-Claude have been making headlines across the world for decades. Since Jeanne-Claude's death

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.