In Focus: A grim masterpiece of the French painter who became the ultimate storyteller in paint

Laura Freeman examines the brilliance and bravado of Eugène Delacroix’s paintings – including an extraordinary recreation of one of the most appalling episodes in human history.

The French word désarroi has no exact equivalent in English. It describes a deep moral turmoil, despair and disorder of the senses. It’s the feeling summoned by the great paintings of Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), who is celebrated in a spectacular retrospective at the Louvre.

His heroes were Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Lord Byron and Goethe’s sorrowful young Werther. ‘He waxes desperate with imagination,’ says Horatio of Hamlet in his wild, ungovernable madness – so, too, does Delacroix as he conjures hells and massacres, Golgothas and fatal last stands.

From the moment Delacroix made his debut, exhibiting The Barque of Dante at the Salon in 1822, he was a showman. He is pyrotechnic and panoramic. More is always more. More soldiers, more slave girls, more souls of the damned, clinging to the bows of Dante’s boat, threatening to overturn it. He paints with rapid, smouldering, bonfire brushwork. Flicks, arabesques and darts convey urgency of expression. His art is an exhilarating, mount-the-barricades, all-muskets-blazing display of brilliance and bravado.

His first wish had been to be a writer. Instead, Eugène, son of Charles Delacroix, Minister Plenipotentiary to the Hague, entered the studio of Pierre Guérin and, when he was 18, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

Théodore Géricault was a fellow student and it was Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819) that would give Delacroix the theme for his Barque of Dante. Although not a poet or a playwright, Delacroix became a storyteller in paint: ‘I could a tale unfold whose lightest word/Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood.’ For lightest word, read his deftest touch with a brush.

One of the most harrowing, most freezing tales Delacroix tells is The Massacre at Chios (1824): the killing and abduction of the entire Greek population of the island of Chios by the Turks. Only 900 of 90,000 inhabitants escaped death or slavery.

What may seem to the viewer excessive or luridly sensational, such as the infant vainly suckling at the breast of his murdered mother – fake news, perhaps, playing on our sense of pathos – was based on eyewitness accounts.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The events of the Greek War of Independence (1821–32) seemed to Delacroix like passages from Dante’s Inferno. He returned to the Divine Comedy as he painted and wrote in his journal: ‘O smile of the dying… embraces of despair.’

The spectacle of his paintings is extraordinary, not least in his most famous work: the 1830 Liberty Leading the People. He looked to the massiness of Rubens. The brooding shadows of Caravaggio. The terribilità – awe-inspiring strength – of Michelangelo. To these, Delacroix brings his own high, flushing, rush-of-blood-to-the-head colours.

Delacroix was uneasy about the label ‘Romantic’. ‘If by romanticism,’ he said, ‘they mean the free manifestation of my personal impressions, my effort to get away from the types eternally copied in the schools, my dislike of academic recipes, then I admit that not only am I romantic, but also that I have been one since I was 15.’

‘Delacroix (1798–1863)’ is at the Louvre, Rue de Rivoli, 75001, Paris, until July 23 – www.louvre.fr/en

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

In Focus: The Norman Ackroyd landscape etchings that have sparked comparisons with Turner

This week marks the last chance to see Norman Ackroyd's sublime exhibition in Richmond. Lilias Wigan urges you to take

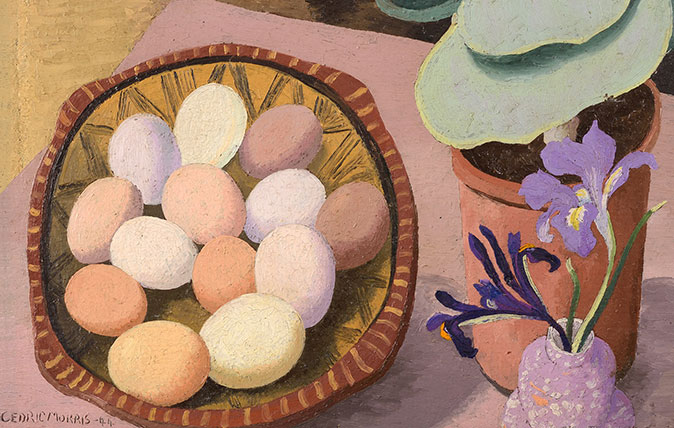

In Focus: The plantsman-turned-artist who found art in flowers, and painted from corner to corner

Cedric Morris's striking still life images have been largely forgotten for three decades, but three new shows are ending that

Credit: Water, by Charles Wheeler ©Estate of Charles Wheeler, via the Ashmoleon

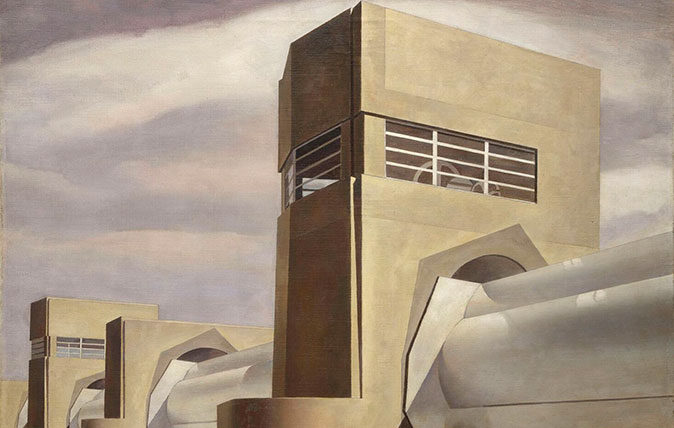

In Focus: Charles Sheeler's cool take on 'America without that damned French flavor'

An exhibition at the Ashmoleon brings together some a wonderful collection of American avant-garde works rarely seen on this side

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

A day walking up and down the UK's most expensive street

A day walking up and down the UK's most expensive streetWinnington Road in Hampstead has an average house price of £11.9 million. But what's it really like?

By Lotte Brundle

-

Life in miniature: the enduring charm of the model village

Life in miniature: the enduring charm of the model villageWhat is it about these small slices of arcadia that keep us so fascinated?

By Kirsten Tambling