In Focus: Leonora Carrington's extraordinary portrayal of Max Ernst, the surrealist pioneer who inspired Dalí

A stunning portrait of Max Ernst, one of the key figures in 20th century art, is at the heart of an exhibition of creative couples at the Barbican's exhibition – but be quick if you want to see it, warns Lilias Wigan.

When Joan Miró gave Leonora Carrington some money one day, asking her to buy him some cigarettes, she ‘gave it back and said if he wanted cigarettes, he could bloody well get them himself.’ Such was the fierce independence of the 20-year-old artist, who had met Miró through her lover, the pioneer of Surrealism and the Dada Movement, Max Ernst.

Carrington (1917–2001) and Ernst (1891–1976) had met at a dinner to celebrate his London exhibition opening in 1937, and, despite Ernst being 28 years her senior, they instantly fell for one another. In 1938, on the brink of the Second World War, Carrington followed her lover back to Paris, where she was introduced to his intimate Surrealist circle, including André Breton, Salvador Dalí and Marcel Duchamp. She and Ernst are among the many creative duos who are singled out for the importance of often overlooked influences between two collaborating artists in the Barbican’s exhibition Modern Couples, which closes on January 27.

Carrington continued to defy the Surrealist habit of casting the female as muse to her male counterpart. She maintained comparative success in both her literary and artistic work and was included in the hugely significant, male-dominated International Exhibition of Surrealism (1938) at the Galérie Beaux-Arts in Paris. Her short story, La Debutante, was one of only two female contributions included in Breton’s Anthology of Black Humour (1940).

After escaping with Ernst from his bitter wife in Paris, the pair moved south to Saint-Martin d’Ardèche in 1938. Ernst supported Carrington’s work. For her first published writings, La Maison de la Peur (1938), he provided illustrations and an introduction, in which he imagines the joining of the couple’s alter egos: he, the ‘Bird Superior,’ she, the equine ‘Bride of the Wind’.

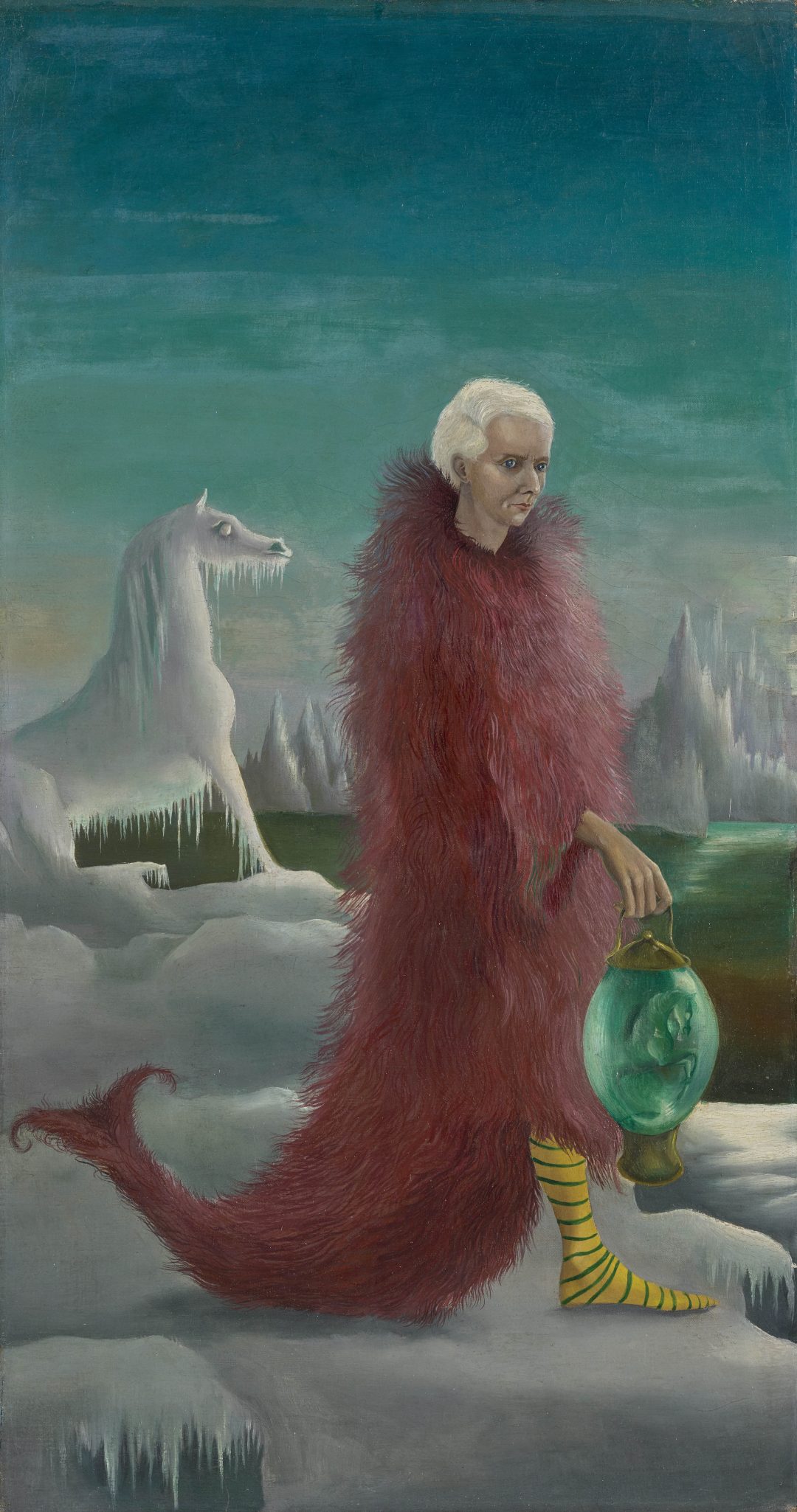

The summer of 1938 spurred an intensely creative period of work, in which they indulged in myths and fantasies around one other. The celestial scene in Bird Superior: Portrait of Max Ernst, c.1939, envisages their relationship at this time. Carrington was inspired by folk tales told by her Irish mother, as well as stories absorbed from the Surrealists in Paris; mythological subjects became a common theme of her work.

In Bird Superior, the white stallion – a surrogate for herself – is twice present, both trapped in the ice and encased in the lantern held by Ernst. He, a shamanic figure dressed in a shaggy feather robe complete with a merman tail and garish striped stockings, looks despondent in the desolate, glacial landscape. The painting conveys a strong sense of the emotional and physical captivity that Carrington felt and from which she was desperate to be freed.

Just two days after the outbreak of war, Ernst was exiled from France because he was considered to be an enemy. Traumatised by this, Carrington descended into mental breakdown and was placed in a psychiatric institution in Santander in Spain. She recorded her brutal experiences, which included sexual assault and fierce forms of therapy, in her harrowing memoir Down Below (1941), blending fact and fiction.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Having escaped the asylum, she later gave the extraordinary bird painting to Ernst in New York in 1942, before moving to Mexico with her new husband, who had facilitated her escape. They never saw one another again.

‘Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde’ is at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, until 27th January. Tickets are available here.

In Focus: The breathtaking sculpture at the V&A with unexplained, frenzied figures writhing in pleasure and pain

Rachel Kneebone's towering sculpture at the centre of some of the V&A's oldest treasures demands your attention in a way

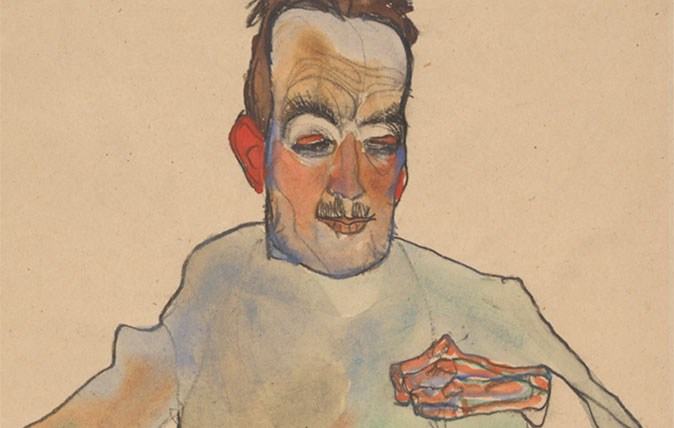

In Focus: A silent cellist, blazing with pleasure, by Klimt's great young protégé Schiele

When he first came on to the Vienna art scene, Egon Schiele hero-worshipped Gustav Klimt. Once they met the two

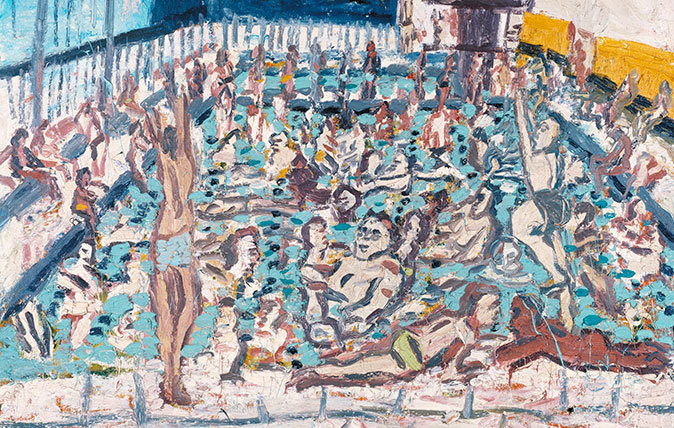

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

In Focus: The unforgettable art of the British WW1 soldier who might have been the Kaiser's son

Karl Hagedorn's contribution to Post-Impressionist art in Britain has been neglected for too long – a new exhibition in Chichester seeks