In Focus: An exhibition that reveals the versatility of art made with scissors

Caroline Bugler is enthralled by ‘Cut and Paste: 400 years of Collage’, an exhibition which celebrates collage from well-known Modern and contemporary artists and unknown or obscure makers alike.

Who knew that Charles Dickens was so handy with scissors and paste? In the years he was busy penning A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations, he found the time to help a friend, the artist William Mulready, assemble a giant folding screen neatly decorated with about 400 engravings of actors, scenes from plays and portraits (including one of himself).

Confronting the visitor at the start of the exhibition, this sets the tone of the show, which adds complexity to the over-simple notion that collage – literally cutting out images and sticking them on paper – was an essentially female pursuit carried out by amateurs until the male Modernists Picasso and Braque came along at the beginning of the 20th century and turned it into high art.

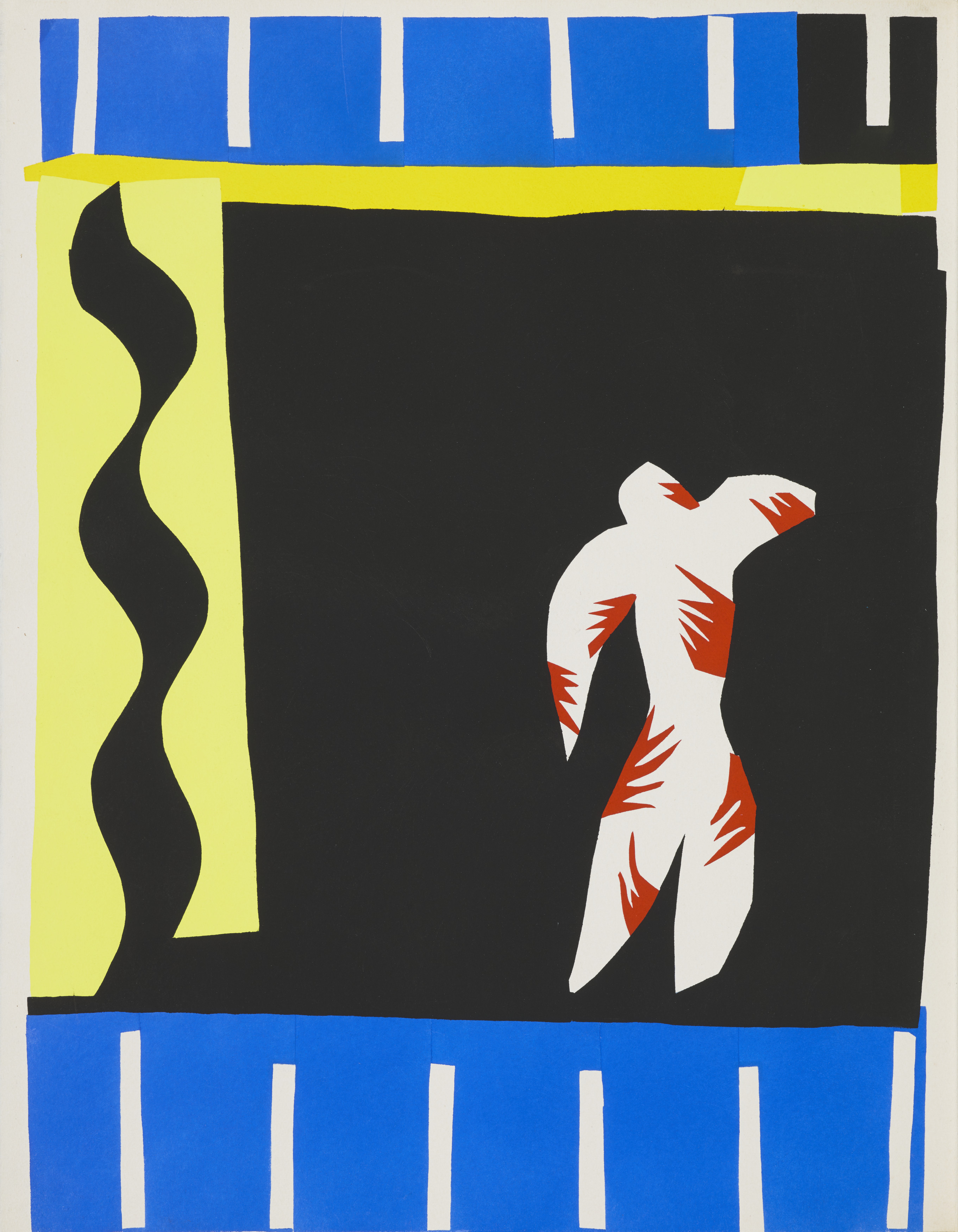

Cutting a vertical slice through 400 years of history, the exhibition feels a bit like a scrapbook filled with a plethora of bizarre, instructive, comical, satirical, polemical, beautiful and ugly images. Some are collage in the strict paper sense of the term; others feature scraps of material, plants, photographs, tinsel, cake decorations or other objects, stuck down, stapled or stitched and sometimes bursting out into three dimensions. Works by many well-known Modern and contemporary artists are represented – Matisse’s dazzling ‘Jazz’ series among them – but some of the most surprising objects are those by unknown or obscure makers.

The earliest examples are ‘flap prints’, showing anatomical figures with paper tabs that can be lifted up to reveal the internal organs. More saucy versions feature fully dressed women, with flaps that can be raised to reveal their underwear.

Some early practitioners of the art, such as Mary Delany (1700–88), were enormously skilled (Books, page 136). Her ‘paper mosaiks’ of plants are so astonishingly lifelike that the few leaves and stems of a real plant cunningly hidden in one of her works are indistinguishable from the paper elements. At its most basic, however, collage is a democratic technique that allows anyone, even the most inept with pencil or paintbrush, to have a go.

The enterprising Victorian publisher John Redington was quick to turn this to advantage. He produced templates for do-it-yourself ‘tinsel prints’, with pre-painted landscape backgrounds onto which buyers could stick engraved figures and adorn them with ready-made accessories cut out from foil.

By the late 19th century, it was even possible to buy chromolithographed scraps purpose-made to stick on packaging, furniture, screens and in albums. Template valentine cards could be customised, too, with lacy and ribbon additions bought from ‘fancy stationers’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Photography added further possibilities for the creators of scrapbooks. When Kate Gough was compiling her photograph album, she cut out portrait heads of family members and inserted them into watercolours to surreal effect. One witty example shows her relatives stuck onto a delicate paintingof apes in a tree, allegedly in response to Darwin’s theories about the descent of Man.

'For the Russian Constructivists, who saw easel painting as a bourgeois conceit, it would ruthlessly eliminate the hand of the individual artist'

The exhibition shifts a gear in Room 2, which catapults the visitor into the early decades of the 20th century. In the hands of Picasso, sticking fragments of newspaper onto paper introduced words into an artistic image, to elegant and amusing effect.

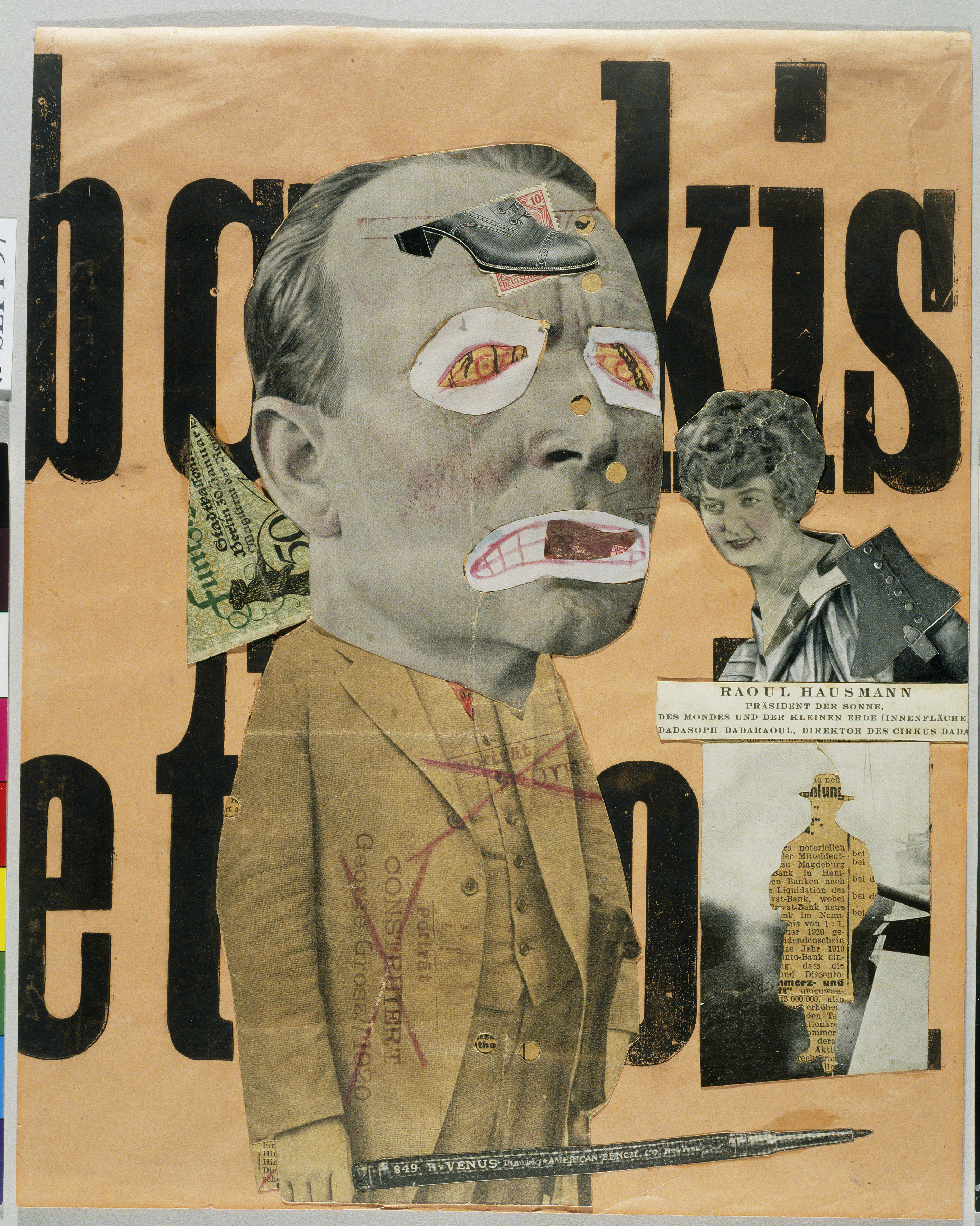

For Futurists such as Carrà, it was the perfect way of conveying the hectic pace of modern life in which everything is chaotic and confusing, defying laws of order, composition and gravity. For the Dadaists George Grosz and Raoul Hausmann, it was a means of venting their disgust with a society that had created the cataclysm of the First World War and allowed them to produce an ‘anti-art’ that flew in the face of traditional painting.

For the Russian Constructivists, who saw easel painting as a bourgeois conceit, it would ruthlessly eliminate the hand of the individual artist and could be harnessed for Revolutionary propagandist purposes.

Because collage enables the maker to juxtapose images that are completely unrelated, it was a perfect vehicle for the Surrealists. The master of these was Max Ernst, who cut up Victorian engravings from popular novels and sales catalogues and reassembled them to produce nonsensical and charming collage novels that are the ancestors of Terry Gilliam’s ‘Monty Python’ animations.

Other 20th-century artists saw it as an opportunity to introduce the ‘real’ world into their work. In the 1930s, John Piper travelled around England with a suitcase full of marbled and textured papers, music scores and tickets, and assembled them into collages in front of the landscape he wanted to depict as he balanced a board on his knee.

As cheap printing resulted in the proliferation of colourful printed images, so collages got bigger and bolder. Pop artists gaily jumbled together images culled from advertisements or magazines, product labels and photographs. Peter Blake used it to create the most famous album cover ever – the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Collage even spread beyond the picture frame and into three dimensions.

The exhibition cleverly weaves in Eduardo Paolozzi’s re-created London studios – part of its permanent display—itself a kind of immersive 3D collage of the sculpture, magazines and flotsam among which he worked.

Contemporary collages are more likely to be done with a computer keyboard, but there is still something seductive about the idea of crafting funny, anarchic and disruptive images by hand with scissors and glue.

In Focus: The Spanish painter whose visceral depictions of martyrdom still have the power to shock

The unflinching representations of brutality in Jusepe de Ribera's images of martyrdom is the focus of a new exhibition, the

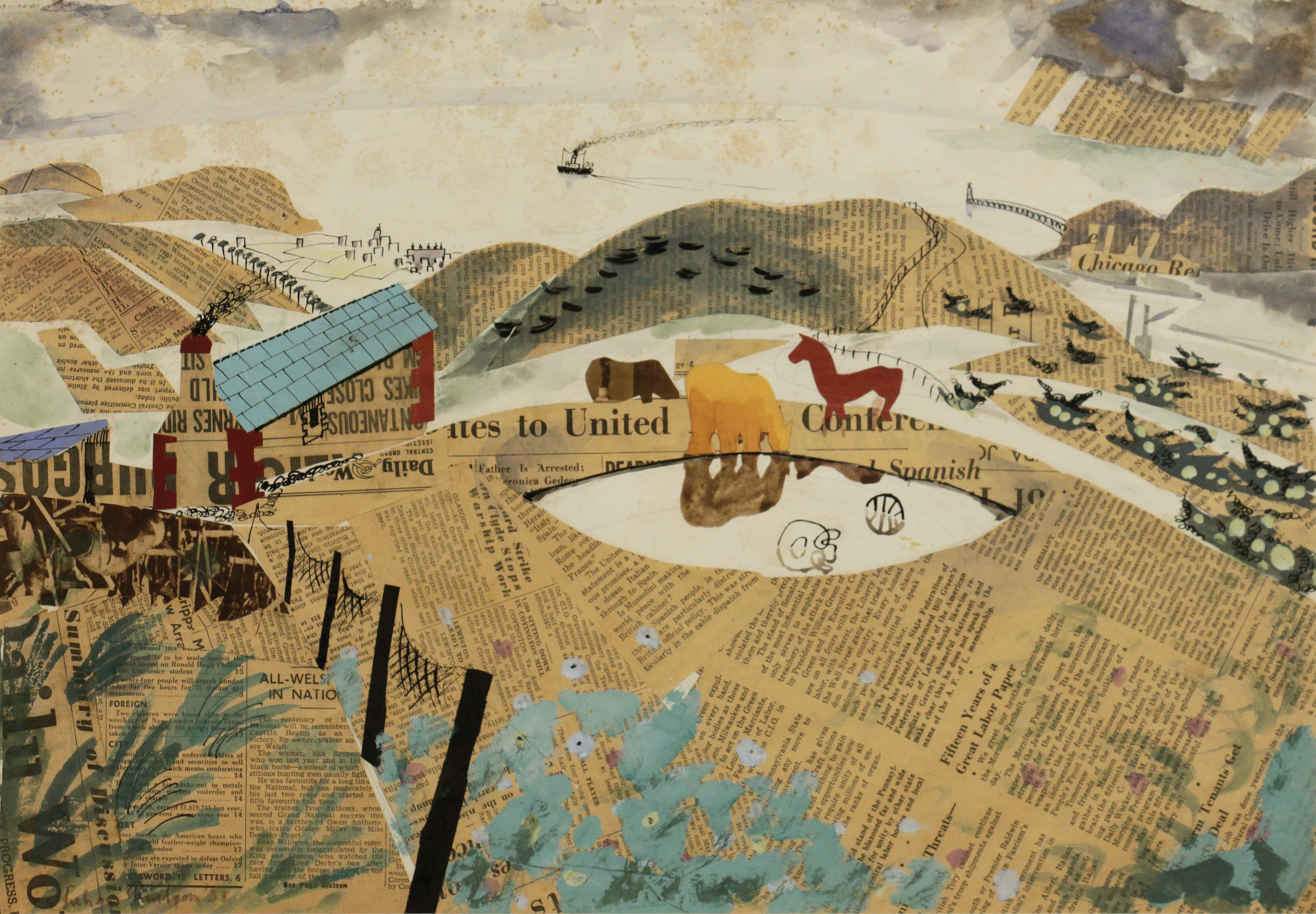

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

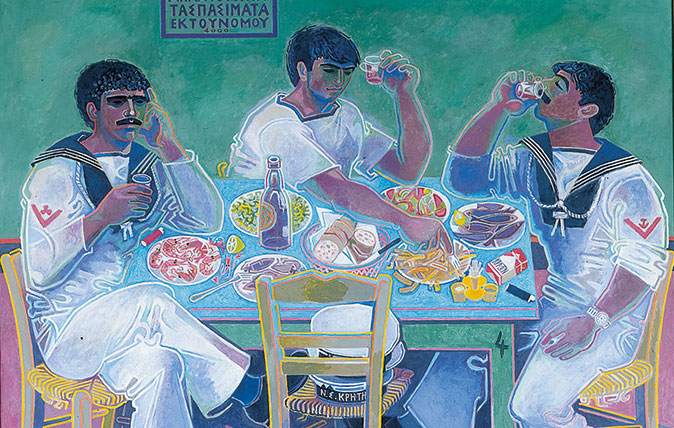

In Focus: The charmed life of Paddy Leigh Fermor and friends in Greece

The iconic writer Paddy Leigh Fermor and two of his friends in Greece – both artists, one a local man and

In Focus: The Mansions of Cornwall, as they existed in 1846

A rare survey of over 80 Cornish country houses has been found and reprinted – Adrian Tinniswood takes a look.

Credit: The Harley Gallery – Clare Twomey's lithophanes, part of The Grand Tour

In Focus: An ethereal exhibition pushing the boundaries of photography, porcelain and the display space itself

Clare Twomey's new exhibition at the Harley Gallery in Nottinghamshire blurs the lines in a fascinating manner: where do the

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.