In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack Bar shows just how pervasive the conflict's consequences were in art and life. Lilias Wigan takes a look.

At the end of the First World War, art was used as a powerful vehicle for rebuilding society and memory in a period of widespread grief and trauma. A new kind of imagery evolved in response to the atrocities and devastation, and Tate Britain’s current exhibition, ‘Aftermath’, explores the different ways art developed in the post-war years. Timed to coincide with the centenary of the end of the war and running until September 24, the exhibition looks at the war’s impact on England, France and Germany and how it was articulated through art.

‘Aftermath’ brings together over 150 works made between 1916 and 1932 by artists including Edward Burra – one of whose pieces we’ll focus on here – George Grosz, Fernand Léger and C.R.W. Nevinson. Although many of the works included are politically charged and often specifically commissioned for war remembrance, there is huge variety in approach, ranging from portrayals of mangled veterans by Otto Dix and Henry Tonks to works inspired by a fascination with technology, such as Léger’s Discs in the City of 1920.

British artist Edward Burra (1905–1976) was too young to have served in the war, but he endured his own suffering throughout his life in the form of terrible arthritis. Painting and drawing consequently became an escape from the physical limitations of his body. Though he never experienced active service, he was an acute observer of the effects of war on society and, through this awareness, combined with the influence of German art and the Dada and Surrealist movements that were then developing in Switzerland and France, he evolved a distinct, if enigmatic, style.

Of the British artists exhibited in the Tate’s exhibition, it is Burra who has most in common with his German contemporaries, particularly Grosz, whose satirical Ecce Homo series of brothels dating from 1922 is reflected in Burra’s The Snack Bar (1930).

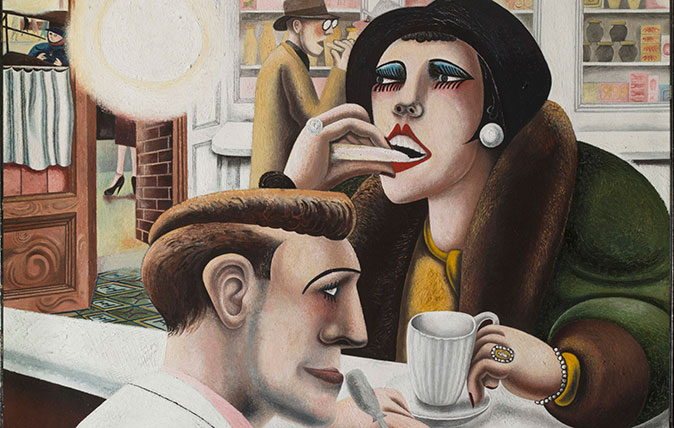

Burra’s scenes often have dark and menacing undercurrents, featuring marginalised characters on the fringes of society. The Snack Bar, though less overtly political than other works, is typical of this: a city bar at night with stark, artificial lighting illuminating a barman opposite his female customer. The man slices a fleshy pink ham while venturing a sideways glance at his client, whose fur coat, jewellery and gaudy make-up suggest she is a prostitute.

The composition is divided by the exaggerated diagonal of the bar. Behind them, two hatted figures converse, while another woman – we glimpse only her legs, one of which is adorned with an anklet – stands on the street beside a car. Burra’s friend Barbara Ker-Seymer described them as ‘only a background to the two main figures’.

Whatever its intended purpose, this background heightens the tension between the man and the woman in the foreground, whose relationship is unclear. The scene is tantalizing and provocative; violence and sexual tension hang in the air. Hands are stretched out towards each other, but don’t touch; the figures lean into one another, but their eyes don’t meet.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Boldly outlined, with inflated hands, they are almost caricatures. The slices of pork resemble the folds of their clothing; the colour of the meat echoes that of the barman’s lips and shirt and the shelving behind. His lip protrudes centrally on the canvas, as though in anticipation.

This is one of the few oils Burra ever painted and there’s a strange dryness to the paintwork, which appears more akin to his usual media of gouache and watercolour. There’s also a certain sensuousness, however, in the juxtaposition of textures and surface detail: the cross-hatched treatment of the bar, the lined-out courses of brickwork, the patterns of tiling and woodgrained window shutter. The harsh overhead lighting catches on the woman’s jewellery as the billboards and streetlights outside amplify the sense of pleasurable possibility in this meeting of the commercial and the erotic.

The artists represented in this exhibition played an important role in helping to rebuild and reshape society after the catastrophic conflict of the First World War. Burra was at his most successful when exploring the complex social consequences of this trauma on modern metropolitan life. For all it’s apparent pleasure, underlying the scene depicted in The Snack Bar are a number of disturbing implications of social anxiety and political instability.

‘Aftermath’ runs at Tate Britain until September 24. Tickets £16 (£15 concs); free for Tate members.

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin Published

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson Published