In Focus: The work by a Bloomsbury Group stalwart which fuses nature, nostalgia and Impressionism

Britist artists Duncan Grant's wonderful versatility allowed him to mix traditional and modern, natural and man-made, as this picture on show at the William Morris Gallery demonstrates. Lilias Wigan went along to take a look.

Gardening in Britain, still a favourite national pastime, underwent an explosion of popularity in the Victorian era – as witnessed from public parks to communal city squares, cottage gardens to the settings of country houses. Horticultural societies proliferated, accompanied by innovations and discoveries in the field of gardening and botany.

The Victorians favoured elaborately structured plot designs and sowing exotic species from around the world – a trend that continued up until the late nineteenth century, when the influential gardeners Gertrude Jekyll (1843–1932) and William Robinson (1838–1935) rejected the formal style in favour of ‘wilder’ planting. Their fashionable methods included growing creepers and ramblers, shrubs and other native plants that, ironically, demanded careful maintenance to achieve a ‘natural’ look.

The Enchanted Garden, at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, explores the importance of the garden’s role in 19th and 20th century British art, spanning works from the Pre-Raphaelites through to the art of the Bloomsbury Group, and including illustrations by the likes of Cicely Mary Barker and Beatrix Potter.

Among the works exhibited is the one we examine on this page, by Duncan Grant (1885–1978). During the First World War the British artist – one of the central figures of the Bloomsbury Group – moved to a farmhouse at Charleston in East Sussex, along with founding member and close friend Vanessa Bell and her family. Together, they decorated the house. The building and its surroundings became a source of inspiration to him and other members of the group’s literary, intellectual and artistic circle: Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf all congregated here from London. Dora Carrington described it as ‘a romantic house buried deep down in the highest and most wild downs I have ever seen’.

Grant’s talent for interior design – evident throughout the house – spread to the garden. He followed Jekyll’s and Robinson’s planting schemes and made them the focal point of his painting, The Doorway (1929). Through the window springs a lively jungle of wild plants and flowers.

Although the view is from a domestic setting, the fluidity of form and colour gives the impression that it was made ‘en plein air’– the technique of outdoor painting employed by the French Impressionists in order to truly capture the visceral feeling of a place.

From 1910, Grant was heavily influenced by the Impressionists. Both he and Bell were included in the notorious Second Post-Impressionism Exhibition, held at the Grafton Galleries in London (1911–12), which introduced contemporary European artists to England. Their work was shown alongside paintings by artists such as Cézanne, Braque and Bonnard, whose influence on Grant is palpable in the succulent colours and staccato brushwork.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In line with Impressionism, Grant’s concern here is with the overall, enchanted spirit of the place over literal representation. A feeling of nostalgia permeates and one senses the excitement he feels for nature’s vibrant colours and the satisfaction derived from nurturing plants.

His daughter Angelica described Grant as ‘a man of instinct, [which] was what made him so different from the rest of Bloomsbury’ and this instinct is evident in the confident swirls of paint. Patterns of foliage are echoed in the walls and floor as though plants have enveloped the interior space, an effect enhanced by the odd, tilted perspective, while a human presence is implied by the red garment casually draped across a chair.

The subject matter is traditional, and the painting is the perfect vehicle for nostalgic contemplation of the British gardening tradition. Yet at the same time, the style is inherently modern – indeed, Grant was among the first artists in Britain to make purely abstract paintings.

The Enchanted Garden is on view at the William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow, until 27th January 2019. Free entry.

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

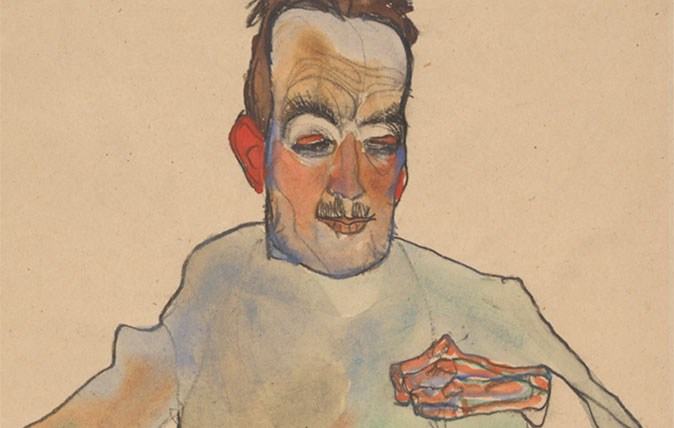

In Focus: A silent cellist, blazing with pleasure, by Klimt's great young protégé Schiele

When he first came on to the Vienna art scene, Egon Schiele hero-worshipped Gustav Klimt. Once they met the two

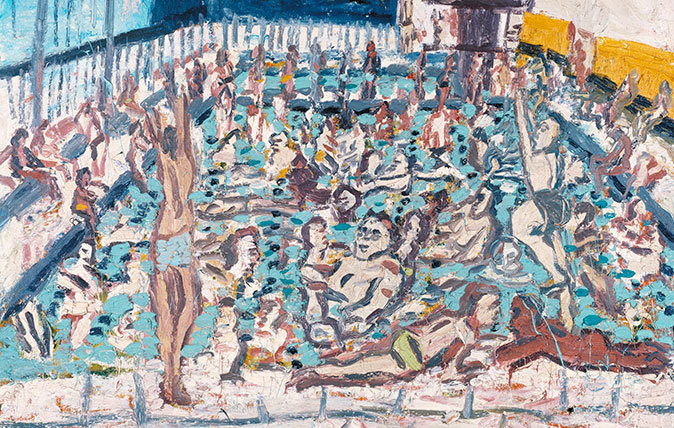

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

In Focus: Bomberg, the trailblazer who led the way for modern British art but died an impoverished war veteran

Coinciding with the sixtieth anniversary of the artist’s death, the touring exhibition of David Bomberg’s work is entering its final