In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of his homeland. Lilias Wigan takes a look at this key work from that time, simultaneously impressionistic and brutally honest.

The Dulwich Picture Gallery recently opened the first major UK showing of the work of Canadian artist David Milne (1882-1953). Arranged chronologically, it begins with Milne’s arrival in the bustling streets of New York, where, aged 21, he intended to pursue a career in commercial illustration.

Enthralled by the city’s museums and galleries, he soon turned his aspirations to fine art. With Impressionist-inspired, pixelated brushstrokes, he painted billboards and street signs, horses and carts — all with radiating energy. This is New York on the brink of modernity.

Moving through the exhibition, the style shifts dramatically as Milne leaves his urban environment. His principal subject is now the natural world; we move from a village in upstate New York to a battered post-war northern France, on to rural north-east America and ultimately back to his native Canada.

Milne’s parents were Scottish immigrants in a rural farming community in Ontario and he was raised to be close to Nature. In 1929, he built a solo camp outside Temagami, a remote mining town north of Toronto. In his tent, he built a wooden floor, installed a stovepipe and lived as a hermit, never venturing further than 5 kilometres away.

He canoed on the nearby lake and nurtured plants, bringing them into his home to work on still-life compositions, and studied the abandoned, flooded mineshafts dotted around the surrounding woodland. Tent in Temagami (1929) does little to romanticise the daily life of this isolated outpost. The reflective pools of the mineshafts offer a dystopian alternative to Monet’s water-garden ponds.

Milne was taken by the effect of minerals that leaked from the rock beds into the swampy water and simplifies these colours so that they make an impact against a mainly black landscape. The swirling forms of subdued colour almost look like camouflage.

Although he had neither financial reward nor artistic recognition during his lifetime, Milne is now celebrated in Canada. This exhibition shows why. It reveals clearly the shifts in his style and his profound connection to the natural world, which he found through a self-imposed solitude.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'David Milne: Modern Painting' is on at the Dulwich Picture Gallery until May 7 – adults £15.50, Concs £7, children and members free – www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk.

If you're interested in finding out more about David Milne, a new book has been published to coincide with the exhibition. David Milne: Modern Painting is edited by Sarah Milroy and Ian A.C. Dejardin (Philip Wilson Publishers; £25).

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

Credit: Michael Armitage, The Flaying of Marsyas, 2017. © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby). Courtesy of the Artist and White Cube.

In Focus: Michael Armitage's image of African violence that points the finger back at the western world

Michael Armitage's The Flaying of Marsyas is the centrepiece of his exhibition in South London. Lilias Wigan examines it in

In Focus: Cézanne's brutally honest portrait of his wife, 'weary and dissatisfied', as their relationship was on the rocks

The National Portrait Gallery's exhibition of portraits by Paul Cézanne comes to an end this weekend. Lilias Wigan takes an

Credit: Bridgeman

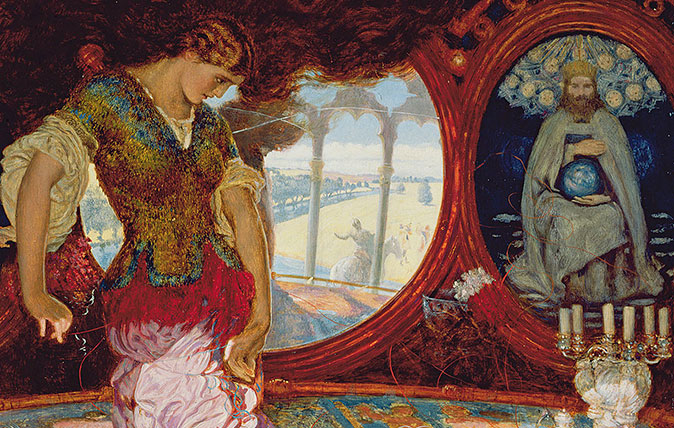

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an