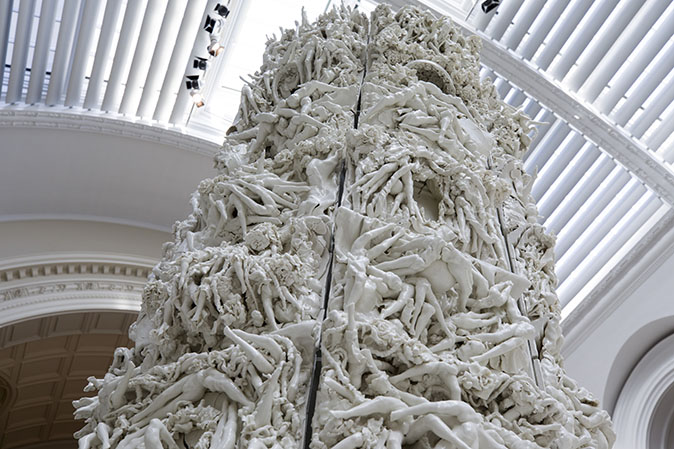

In Focus: The breathtaking sculpture at the V&A with unexplained, frenzied figures writhing in pleasure and pain

Rachel Kneebone's towering sculpture at the centre of some of the V&A's oldest treasures demands your attention in a way few works ever do. Lilias Wigan takes a look.

Standing like an architectural pillar among the V & A’s collection of Renaissance and Medieval art is a monumental porcelain tower by Rachel Kneebone.

At five metres high, it is one of her largest sculptures to date and it commands attention in the room. The principal feature of this multilayered monolith is the legs. Ceramic limbs flail outward from the panels, exploding from the central chamber. It is hard to discern whether they writhe in pleasure or in pain, but they are intricate – detailed down to the toenails.

Sprouting from between them, plants and shrubbery breed unchecked. The structure is built from panels arranged like bricks or storeys of a building. Cornices and architraves are semi-concealed, often buried in foliage. Classical-style columns shoot from the top tier, supporting unexplained, frenzied figures.

But in the chaos of these disparate parts, patterns unfold; the arrangements of self-multiplying legs appear to respond to each other with satisfying, underlying harmony.

The title, 399 Days (2012-13), recognises the time it took from the mould’s arrival at Kneebone’s studio to finishing firing the porcelain. While the name does little to relieve the obscurity of the sculpture, Kneebone intends it this way, stressing she doesn’t ‘have an authority over what the work is’.

Although the piece appears to be unfinished – the panels don’t quite connect and huge fractures have formed at the base, as though it can’t bear its own weight – the sculptor feels every part of it ‘to be complete and as it should be’.

In the physical commotion of the piece, it exists somewhere in between architecture and sculpture, fluidity and solidity, the conscious and the subconscious.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In a constant state of flux, the whirling limbs make the rigidity of the structure seem fragile. They remind us of Hieronymus Bosch’s ashen figures and mystifying scenes in The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Kneebone’s monument exists in a territory that dissolves the scope between the historical collections at the V&A and contemporary art. This is a visual feast on which one cannot help but gorge.

399 Days is on display in room 50a at the V & A until January 2021. Admission free. See www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/rachel-kneebone

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

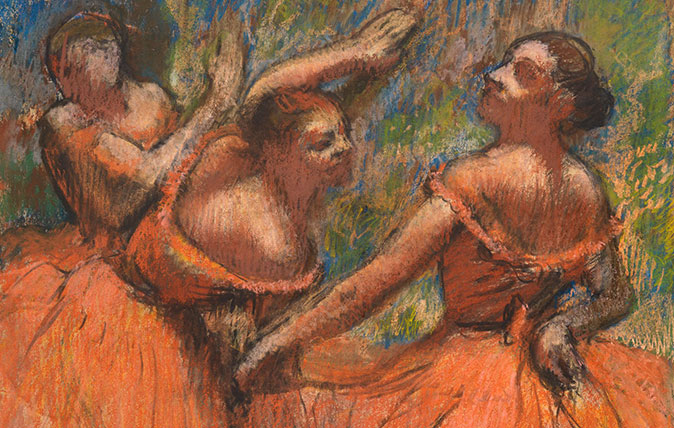

Credit: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - The Burrell Collection, Glasgow © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

In Focus: The Degas painting full of life, movement and 'orgies of colour'

Lilias Wigan takes a closer look at one of the key work's at the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery

In Focus: The Norman Ackroyd landscape etchings that have sparked comparisons with Turner

This week marks the last chance to see Norman Ackroyd's sublime exhibition in Richmond. Lilias Wigan urges you to take

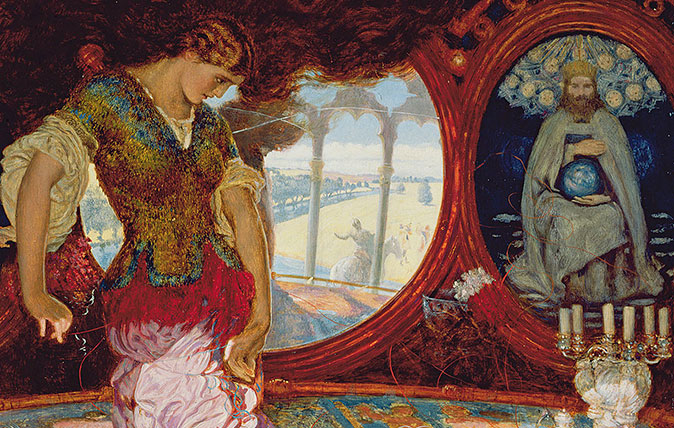

Credit: Bridgeman

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

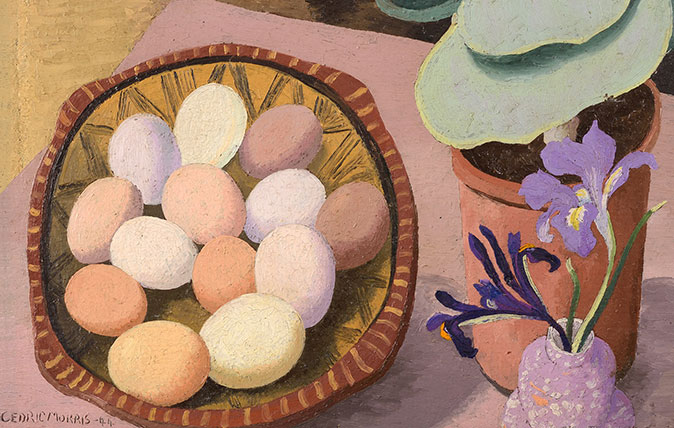

In Focus: The plantsman-turned-artist who found art in flowers, and painted from corner to corner

Cedric Morris's striking still life images have been largely forgotten for three decades, but three new shows are ending that