In Focus: Bomberg, the trailblazer who led the way for modern British art but died an impoverished war veteran

Coinciding with the sixtieth anniversary of the artist’s death, the touring exhibition of David Bomberg’s work is entering its final showing at Ben Uri Gallery and Museum in St. John’s Wood. Lilias Wigan paid a visit.

The middle child of eleven siblings, David Bomberg was born in Birmingham in 1890 to Polish-Jewish émigré parents. In 1895, the family moved to east London, where he was brought up among the ‘Whitechapel Boys’. Despite being raised in a poor immigrant household, he was able to attend the Slade School of Art with help from The Jewish Education Aid Society.

He was expelled from the school in 1913, because of his radical approach, but subsequently taught celebrated artists, including Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, and also motivated the formation of ‘The Borough Group’ in 1946. Yet he received little acclaim or commercial success during his lifetime and died in virtual poverty in 1957.

This exhibition is the only major survey of Bomberg’s work since the Tate’s retrospective in 1988 and Spirit in the Mass at Abbott Hall Gallery in 2006. Through portraiture, landscape paintings and graphic art, it explores his engagement with subjects ranging from Jewish and Yiddish culture to war, poetry and dance.

'Bomberg’s art was innovative and stimulating at a time when Britain lagged behind'

The experience that most affected Bomberg’s style was his involvement in both world wars – at the Western Front, from 1916, and subsequently as a commissioned (albeit unsuccessful) war artist. Art historian Richard Cork explains that his ‘prolonged and searing encounter with the armaments of modern war engendered a crisis in his way of seeing’. His harrowing experiences in the trenches and the death of his brother at war brought an overriding sense of disillusionment with the world and marked his work irrevocably.

The idealised notion of the machine world that dominated much of Bomberg’s early work transformed as he realised first-hand how devastating it was. Without much artistic opportunity at the Front, he turned to poetry and verbalised his horror in phrases such as ‘demoniacal banging’ and the ‘very hell about our heads’. He found the violence so unbearable that he deliberately discharged his rifle into his foot in order to be re-posted.

In the first room is a pairing of paintings of the same scene, made seven years apart. Both depict a woman, modelled by his sister Raie, staring from a bedroom window with one foot propped up on a chair. In Woman looking through a window, often known as Bedroom Picture (1911-12, pictured at the top of the page), light pours through the open window onto a domestic scene – one that was no doubt heavily influenced by Bomberg’s evening class tutor, Walter Sickert. The painterly depictions of daylight spreading over the ruffled bedsheets and ornaments give a sense of optimism, while the side-door lies ajar, allowing an intimate glimpse into the artist’s studio.

When Bomberg revisits the subject, his change in style is drastic. In At the Window (1919), he reduces finer details and daily clutter to essential geometric forms, appropriating technical devices used by the English Vorticists. Painted after his war experience, the later work reflects Bomberg’s changed attitude to mechanisation.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The harsh red palette, together with the austere angularity of the woman’s figure, bear the language of violence as well as exaggerating her confinement. The composition is cropped claustrophobically, with no sight of the other room. The window that before yielded light has become a narrow grid resembling prison cell bars.

The woman’s black clothing also takes on new meaning, implying a mourning of the futility of life lost in battle. The optimism of the earlier painting is transformed, through this figure with her head cupped in her hands, to grief and fear.

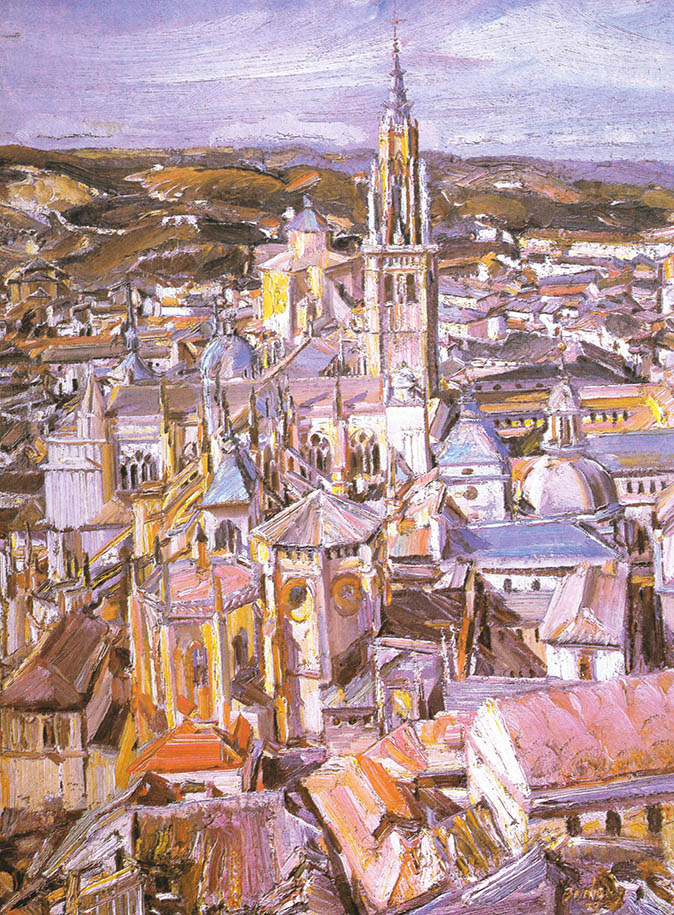

After the war, Bomberg wanted to get away from London – ‘the steel city’, as he referred to it. The following rooms of the exhibition show how much of the rest of his life was spent rediscovering Nature – admiring its ‘pure form’ and making every effort to encapsulate its essence. His style became more figurative, as is most apparent in his landscape paintings of the Middle East and Spain, as well as his portraits of those close to him.

Bomberg’s art was innovative and stimulating at a time when Britain lagged behind other countries in attitudes to Modern art. This exhibition makes us question why his recognition as one of the most radical British artists of the 20th century was so delayed.

Bomberg is on view at Ben Uri Museum, 108A Boundary Rd, London NW8 0RH, until 16 September 2018. Tickets £5/Concessions £4. See benuri.org.uk/exhibitions-new for more details.

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

Credit: Bridgeman

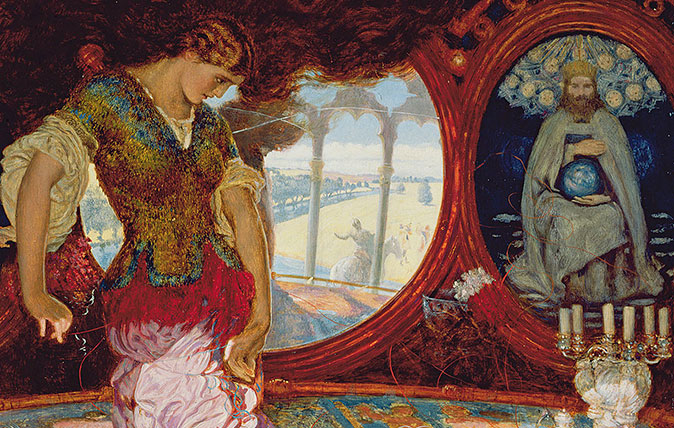

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

In Focus: The Norman Ackroyd landscape etchings that have sparked comparisons with Turner

This week marks the last chance to see Norman Ackroyd's sublime exhibition in Richmond. Lilias Wigan urges you to take