In Focus: The ancient roman temple which lay under London, undiscovered for over 17 centuries.

The temple of Mithras has been beautifully restored by Bloomburg SPACE and now sits under their Headquarters by Bank tube station.

In November 2017, Bloomberg SPACE opened its new European headquarters in the heart of the City of London. Grandly but discreetly, it tucks in between two stations, Cannon St and Bank. This busy pedestrian thoroughfare is where recorded London began and the earliest major settlement in London was established by the Romans in the first century AD.

Starting out at the confluence of the River Thames and Walbrook River and extending north, clinging to the banks of the Walbrook, a lively centre of industry and commerce developed. Glass furnaces, tanneries, potteries and bone workshops bustled.

Over the centuries, the river valley has relinquished many remains of Roman tools, clothing and debris, providing evidence of the ancient past and an impressive collection of these artefacts is on display at Bloomberg SPACE.

Norman Foster’s design of the new headquarters was greatly led by the rich history of its location. It is the biggest stone project in the City of London for a century, featuring 9,600 tonnes of Derbyshire sandstone and combining locally sourced natural materials.

The entirely new building straddles the original course of the Walbrook, London’s most mysterious ‘lost river’, now completely subterranean. It also stands over one of the UK’s most significant archaeological sites - the ancient Roman place of worship and ritual, the Temple of Mithras.

The temple now lies 7 metres below street level in its original location but to the Romans it was more or less ground level. Since Londinium was founded around AD 43, centuries of redevelopment have added to the land, increasing it to the level it is today. The Walbrook River, then en plein air, was crucial to the Roman settlement as a source of water and means of transport and sluicing away of waste.

London Mithraeum, built by the Romans in c 240 - 250 AD, is central to Bloomberg’s design. The project took 10 years to complete. Archaeological work, carried out by Museum of London Archaeology under Bloomberg, reinstated the temple almost exactly to its original position under what is now Bloomberg’s headquarters, where it was first discovered in the aftermath of the London Blitz in 1954.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Assiduous deconstruction of the botched relocation 100 metres away to allow for post-war development in 1962 and the reconstruction back on site, using mostly original materials, are a far cry from the incorporated crazy paving of the 1960s!

Mithras was a Roman deity typically depicted slaying a bull in a cave. The 1954 excavations unearthed the sculpted head of Mithras now in the Museum of London but his body was never discovered. Another key sculpture from the temple depicts the tauroctony or bull slaying scene with an inscription stating that an army veteran named Ulpius Silvanus 'fulfilled his vow’.

It is thought that it is he who may have built the temple. Mithraism was a men only club and its rituals and activities remain a ‘mystery religion’ but it is known that it was often associated with the military and many of its members were merchants and civil servants from across the Empire, so it was well placed in industrious Londinium.

A visit to the London Mithraeum, now open to the public, is an immersive experience. A black stairway leads to the underworld. The room is dark and hazy. Light installations, in formation adhering to the positions of the missing seven columns on either side of the temple’s nave, are subtle and effective 3-dimensional devices suggesting the structure’s lost verticals.

A contemporary sound installation collages imagined sounds of the time. Voices chant in Latin and sandaled feet shuffle on the temple floor, bringing to mind the Roman sandal in the vitrine display at ground level above.

The contemporary theatrical effects, designed by New York based creatives, Local Projects, are atmospheric and striking and show a new approach to how we present archaeology. Bloomberg said ‘we wanted to use innovation to create less of a museum and more of an experience.’

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

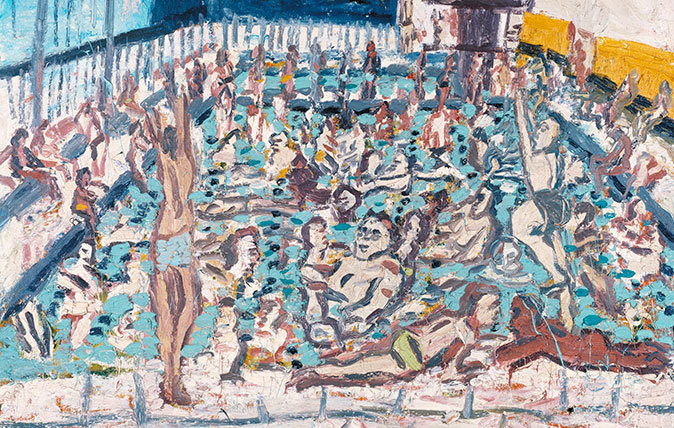

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

Credit: The Harley Gallery – Clare Twomey's lithophanes, part of The Grand Tour

In Focus: An ethereal exhibition pushing the boundaries of photography, porcelain and the display space itself

Clare Twomey's new exhibition at the Harley Gallery in Nottinghamshire blurs the lines in a fascinating manner: where do the

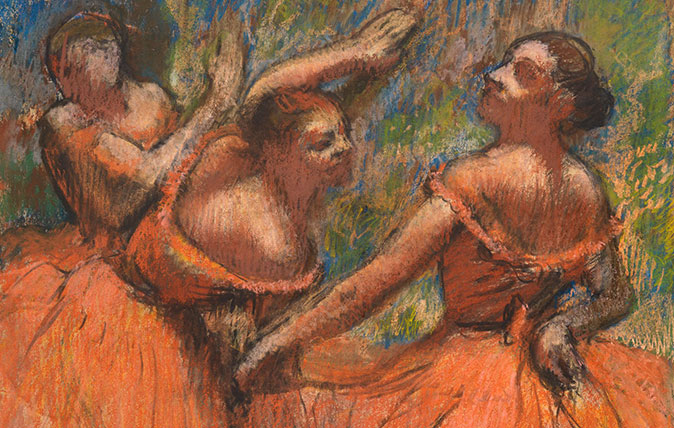

Credit: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - The Burrell Collection, Glasgow © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

In Focus: The Degas painting full of life, movement and 'orgies of colour'

Lilias Wigan takes a closer look at one of the key work's at the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery

In Focus: Bomberg, the trailblazer who led the way for modern British art but died an impoverished war veteran

Coinciding with the sixtieth anniversary of the artist’s death, the touring exhibition of David Bomberg’s work is entering its final