In Focus: The 160-year-old ‘Photoshopped’ picture which shocked Victorian England

An exhibition looking at four of the giants of Victorian photography has at its centre a remarkable work by the great Oscar Rejlander. Michael Murray-Fennell explains all.

We tend to think of photographic manipulation as a modern phenomenon, made possible by digital technology and Photoshop software. Yet the practice is almost as old as photography itself – nearly a century and a half old.

Take Oscar Rejlander’s groundbreaking Two Ways of Life (1856–7), a picture made up of more than 30 seamlessly combined negatives. It places Rejlander in the centre, with the choice between a virtuous and sinful life on his left and right, respectively.

The photograph shocked the public, not just for the nude women, but also for the fact that, in its scale, ambition and references to Renaissance art such as Raphael’s The School of Athens, it was a direct challenge to the supremacy of history painting.

Today, it's the mainstay of Rejlander’s reputation, and one of the central images on display at a new exhibition, ‘Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography’, which runs at the National Portrait Gallery in London until May 20.

The exhibition’s curator Phillip Prodger is at pains to point out that the Swede quickly abandoned such composite prints. Instead he concentrated on photographs that were ‘designed emphatically to stand on their own without deference to another medium.’ And with good reason.

By the middle of the 19th century, photography was hammering at the door of the pantheon of the Arts. Many sought to bar its entrance, at best patronisingly relegating it to a subordinate role as a handmaid to fine art.

The pioneering Rejlander was not adverse to painters using photography as a helpful tool for their own work, but for him, this emerging art form was no lowly servant. Instead, the Swede insisted, it was ‘high-born… nursed by a most respectable Mrs Chemistry.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

That chemical nurse was the wet-plate collodion process, a dramatic improvement on the earlier daguerreotype and calotype methods, which allowed not only for greater detail, but for greater speed in the capturing of that detail.

Those glass negatives coated with collodion and sensitised with silver nitrate would finally deliver on an earlier claim that photography was ‘the art of fixing a shadow’.

For Rejlander, the shadow was more psychological than literal. ‘I regard art as a means of making thought visible,’ he wrote in 1867, ‘and the skill with which the photographer could do that betokened the true artist.’

The National Portrait Gallery has brought together the works of four photographers who together were at the forefront of testing and expanding photography’s ability to convey a person’s personality, whether it was in the hint of a smile or the light behind the eyes. As well as Rejlander, these Victorian giants – as the gallery describes them – were Lewis Carroll, Julia Margaret Cameron and the all-but-forgotten Clementina Hawarden.

The four did not form a school as such, but they knew each other. Rejlander and Carroll visited Cameron on the Isle of Wight. All three shot Tennyson; Carroll and Cameron both photographed Alice Liddell, the inspiration for Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland books.

Hawarden sought advice from Rejlander, the most senior of the group, and Carroll greatly admired Hawarden’s portraits, preferring them to Cameron’s, which he found ‘all purposely taken out of focus’.

Of the four, Hawarden’s photographs are the most mysterious, not only because she is the least well-known, but also on account of her expert use of light and shadow to create a melancholic and intimate atmosphere. The portraits of her adolescent daughters – seen more often than not by an open window – show them either lost in thought or gazing into mirrors, their reflections staring past the viewer.

The exhibition is full of portraits of children. The curator argues in the superb accompanying catalogue that they ‘represented the blank slate of humanity – the potential to experience pure thought and feeling before the corruptions of modern life intervened’.

Carroll’s photographs of the young Liddell girls are well-known and his shot of Alice from 1858, with her bobbed hair, ragged dress, bare feet and her hand on her hip, is as cute and impish as anything by Cecil Beaton. A side profile photograph from that same summer shows her looking more forlorn.

Cameron’s portraits of her, made over a decade later, depict a woman who frankly appears fed-up with being an artists’ muse, be that of a photographer or writer.

Despite the misgivings by Carroll about Cameron’s photographs (a sentiment echoed by Charles Darwin, who complained about the ‘muzziness and indistinctness’ of her portrait of him), it is Cameron who, of the four, emerges as the star of the show.

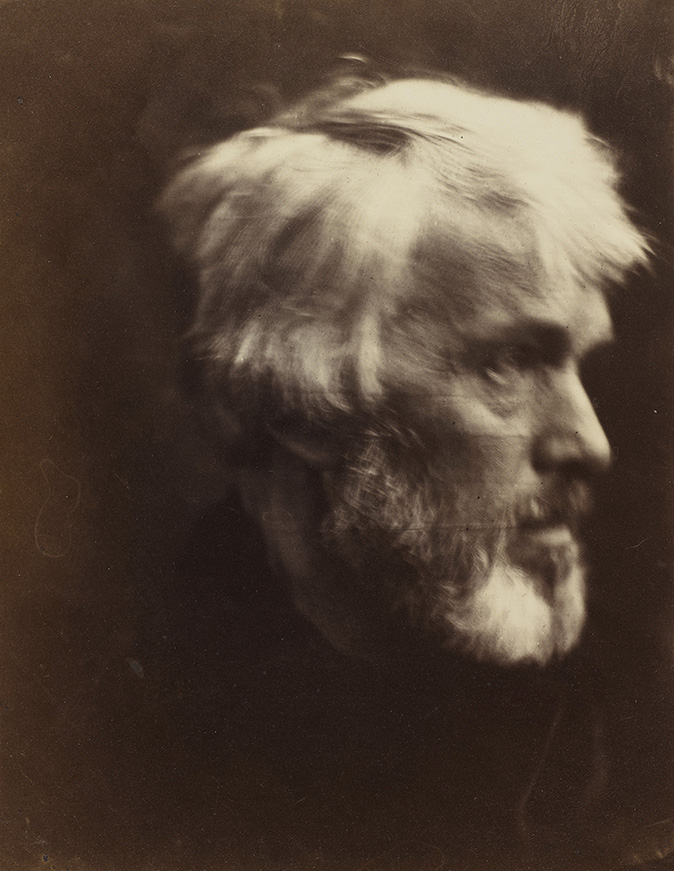

She shows Darwin with fretful eyes, as if worried about the impact of his great work, and her portrait of Thomas Carlyle – a disembodied head, ethereally lit up – portrays him as the very definition of the ‘great men’ of history he espoused. Elsewhere, the model, Mrs Keene, stares out at us with an immediacy that even after all those years is undimmed.

To borrow the different categories of photography as defined by one of Cameron’s early teachers, if Rejlander’s portrait of Tennyson is mechanical and Carroll’s artistic, then Cameron’s – dark, bold and brooding – is ‘High Art’.

If the other three hinted at photography’s status as an independent art in its own right, Cameron’s body of work was a decisive argument that photography had its own language, its own aesthetic and its own capacity for greatness.

‘Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography’ is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, WC2, until May 20. www.npg.org.uk

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.