My favourite painting: James Naughtie

'The word that comes to my mind is always humanity, even when there isn’t a person to be seen in the picture.'

Catterline in Winter, 1963, by Joan Eardley (1921–63), 47½in by 51½in, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

James Naughtie says: This painting takes me home. I didn’t grow up in sight of the sea, but Joan Eardley’s picture of the place where she lived and worked for the last years of her (short) life is an evocation of north-east Scotland that moves me with its spirit. The light, the power that the landscape seems to hold, the tumult of a coming storm: all this reminds me of the fields and the skies that I knew as a boy. She could paint a sunny day and find violence just under the surface or cover her canvas with a wild sea and reveal a strange stillness at the heart of it. The word that comes to my mind is always humanity, even when there isn’t a person to be seen in the picture. She could conjure up all the threat of a lowering sky, or the bitter chill of the east wind on a winter’s day, and make it seem utterly natural: the way things are. She became celebrated first for her street portraits of children in Glasgow, but, for me, she’s a poet of the landscape. I look at this picture, and I know where I come from.

James Naughtie is Special Correspondent and Books Editor for BBC News. His new novel, Paris Spring, was published last month

John McEwen comments on Catterline in Winter: By the time Joan Eardley died tragi- cally young from cancer, Douglas Hall—who, as founding Keeper, established the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art as Britain’s first world-class contemporary art museum—had already proclaimed her right to international stature by buying this and others of her paintings to hang alongside her favourite Soutine and in the sympathetic company of de Staël, Vuillard, Bonnard and Jackson Pollock. ‘I suppose I am essentially a romantic,’ she said, the year of this painting and of her death.

Eardley drew inspiration from two outdoor subjects, wild in their different ways. In Glasgow, her mother’s home town, where the family moved from London to avoid the bombs and she attended Glasgow School of Art, she liked to paint the urchins in the city’s slums. In Catterline, a small fishing village south of Aberdeen, where she had a house from 1954, she painted the landscape, especially stormy seas, identifying with the harsh con- ditions so intensely that description verged on abstraction.

A close friend, Audrey Walker, wrote ‘there were two Joans’, gentle and strong, approximating to the summer and winter sea. It was the rarely revealed ‘winter-sea’ Joan she most admired: ‘the tough, cussing, swearing, bull-dozing indomitable creator of what may be masterpieces... This Joan was to me godlike, and her courage and triumph over the appalling conditions in which she painted... when so often she was suffering physical pain, is something to make an ordinary creature very humble.’ The bleak Catterline in Winter speaks of that empathy and heroic commitment.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passions

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passionsVincent Zanardi reveals the present from his grandfather that he'd never sell and his most memorable meal.

By Rosie Paterson

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

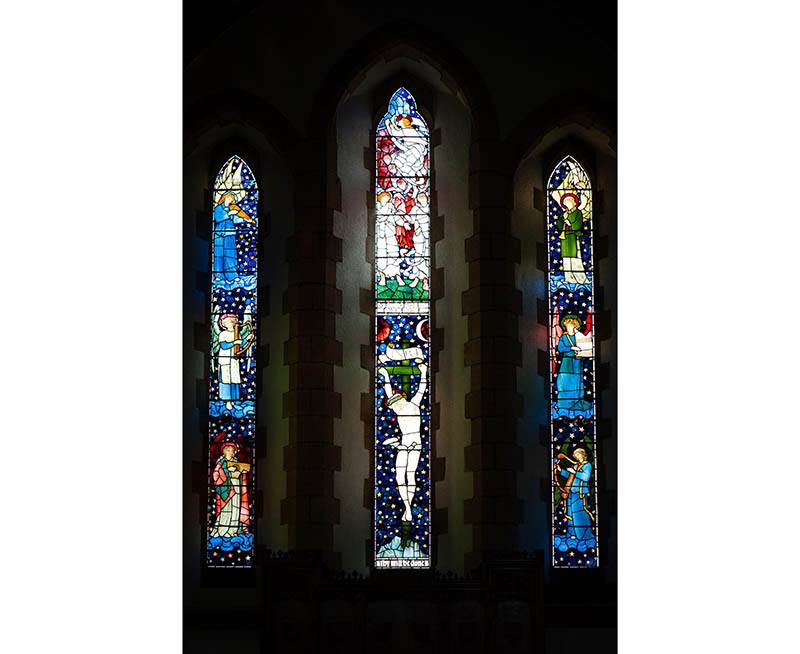

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

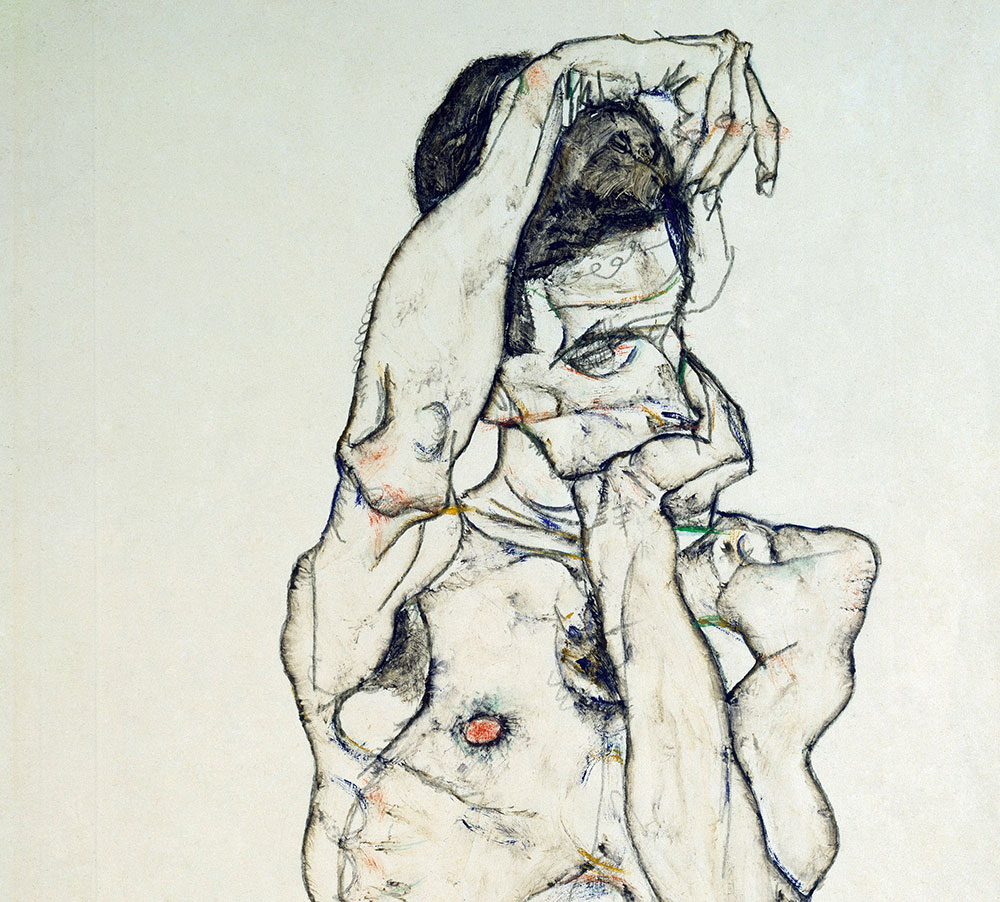

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life