My Favourite Painting: Hilary McGrady

Hilary McGrady, director-general of the National Trust, chooses a painting she first encountered in childhood.

Hilary McGrady on Hambletonian

When I was growing up in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, real art was a rare thing. I loved art in all its forms as a child and I studied art history at school. Our teacher took us to the National Trust’s Mount Stewart and what I remember most vividly is Hambletonian, hanging atop the beautiful entrance staircase.

I had seen it in my textbooks, but it was only when it was brought to life that I truly appreciated its depth and power. To this day, it remains one of my favourite paintings.

Hilary McGrady is director-general of the National Trust

John McEwen comments on Hambletonian

The Tate’s 1984 Stubbs exhibition was curated by the late Judy Egerton, a feisty and always lamented scholar, then assistant keeper of the British Collection. She opened her catalogue introduction with Josiah Wedgwood’s complaint ‘I can scarcely make anybody believe that he ever attempted a human figure’ and her chief aim was to show what ‘a perceptive observer of human beings’ Stubbs was.

A ‘master of the art of class distinction’, he was no moralist in Hogarth’s tradition. Servants are portrayed without condescension: they ‘take pride in what they do, but they make no statements either of the Puritan ethic of work or of the Leveller tradition of equality’.

It was an attitude that reflected that horse racing was ‘perhaps the greatest force for democracy in Georgian England’. The catalogue cover was a detail of Hambletonian’s groom and the trainer Thomas Fields.

This life-size masterpiece was painted for the Durham baronet Sir Henry Vane-Tempest when Stubbs was 75. The Newmarket match race over four miles between the North’s Hambletonian, St Leger winner, and the South’s Diamond, Newmarket champion, attracted ‘the greatest concourse ever seen’ at the home of horse racing.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Hambletonian, a grandson of Eclipse, won by half a neck. Another painting, uncompleted due to a dispute over payment for the first commission, would have shown the finish, with jockey Frank Buckle in Vane-Tempest silks.

Egerton disagreed with Basil Taylor, the pioneer Stubbs scholar, that his hero was, with Leonardo, ‘the greatest painter-scientist in the history of art’. She saw Stubbs’s famed study of equine anatomy and his scientific interest in pigments and print methods as a means to achieve greater reality and to help his work’s longevity.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in Kent

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in KentGrade I-listed Holwood House sits in 40 acres of private parkland just 15 miles from central London. It is spectacular.

By Penny Churchill

-

What the cluck? Waitrose announces ‘trailblazing’ pledge to help improve chicken welfare standards

What the cluck? Waitrose announces ‘trailblazing’ pledge to help improve chicken welfare standardsWaitrose has signed up to the Better Chicken Commitment, but does the scheme leave Britain open to inferior imports?

By Jane Wheatley

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

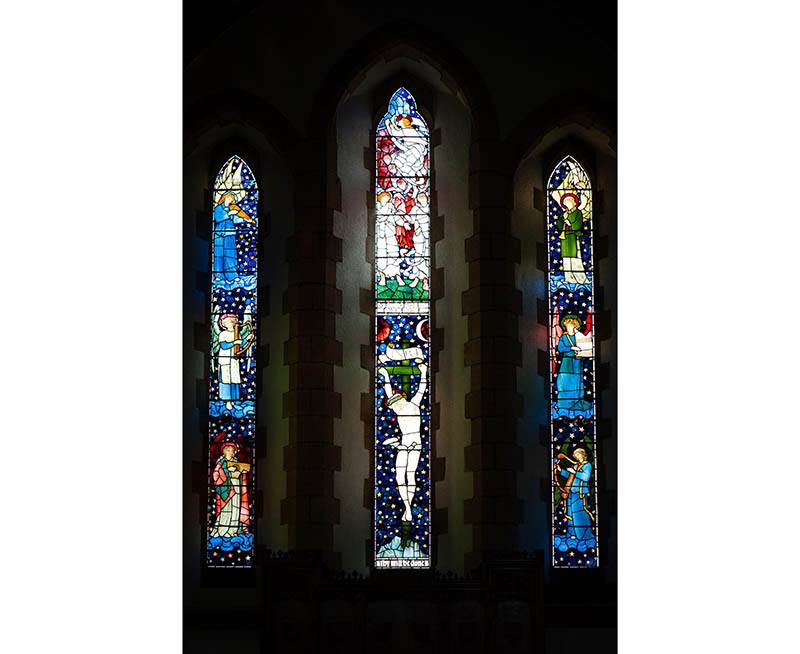

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

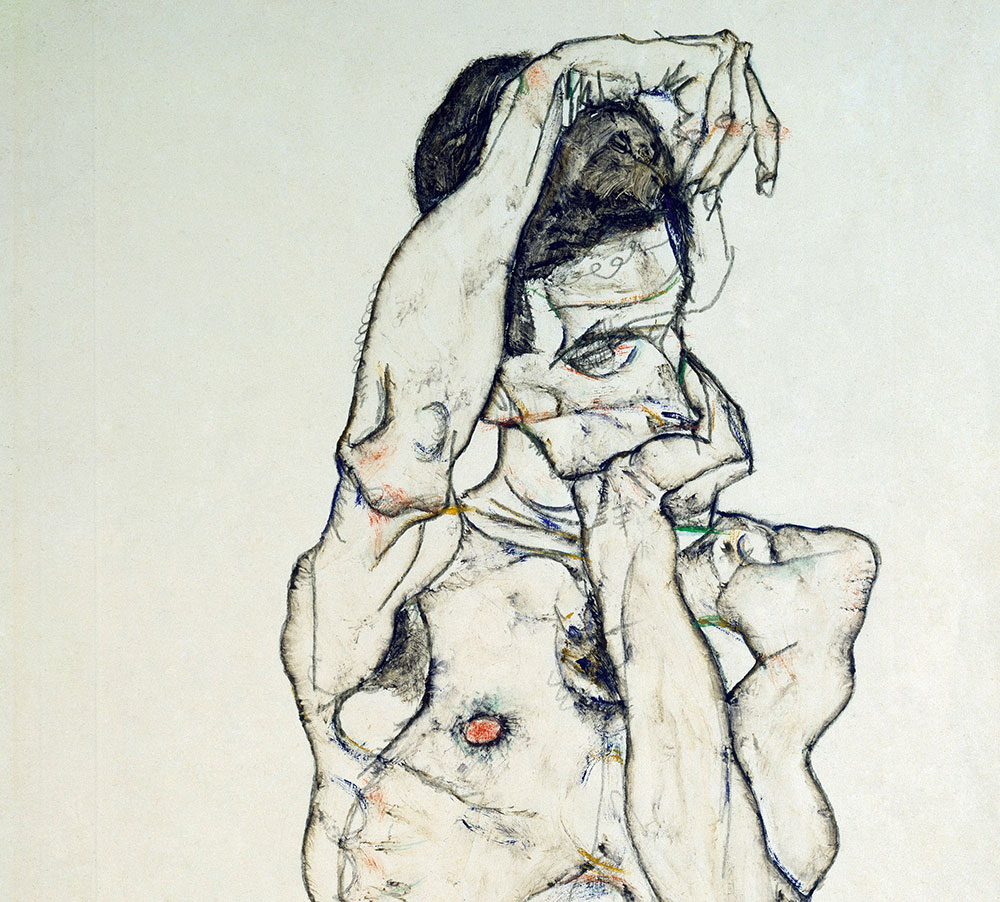

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life