Eyes wide shut: The art of sleeping

Sleep takes many shapes in art, whether sensual or drunken, deathly or full of nightmares, but it is rarely peaceful. Even slumbering babies can convey anxiety, discovers Claudia Pritchard.

With one hand flung above her head, the other in her lap, the sleeping figure in Dod Procter’s Morning has a monumental quality. The painting’s stone-grey tones and simple solidity embody both classicism and bold modernity and, when it was displayed at the Royal Academy (RA) Summer Exhibition nearly 100 years ago, it caused a sensation. Voted picture of the year in the 1927 show, it was bought by the Daily Mail and given to the nation.

There followed a rush of excitement when the painting was trundled around 23 British galleries, viewed by thousands and shipped to New York for more adulation before coming to rest, peacefully, at Tate Modern. But the sleeper is not always such a tranquil presence in art as Morning’s 16-year-old model, Cissie Barnes, a Cornish fisherman’s daughter—indeed, sleep appears as a state almost as varied and complex as the waking hours.

Sleeping and dreaming seem inextricable, a handy device for the artist who sets out to show several things happening at once, but also for religion, signalling a deity’s intentions. Perhaps none is as promising as Jacob’s ladder, his dreamt stairway to Heaven. On the west façade of Bath Abbey, the building’s strong vertical lines lend themselves to sculpted rungs that soar straight to the sky, whereas in William Blake’s depiction of Jacob, the route to eternal life is a whirling spiral, thronging with graceful angels bearing pitchers, dishes and scrolls. The destination is alluring, if your head for heights will let you tackle the steps that rise between the stars, in mid air.

Not all dreams are comforting, however. The Swiss-born artist Henry Fuseli made a speciality of dystopian scenes, conjuring up the sort of nightmare that jolts you awake and leaves a lingering sense of unease. As did Morning, albeit in 1782, his Nightmare created a stir at the RA and made the artist’s name. His female model, too, wears a clinging white gown, but in her room are the dreamed figures of a malevolent and lustful incubus and a horse—literally a ‘night mare’.

Fuseli had hit the jackpot, repeating the idea in further pictures and becoming more widely known through the many prints of Nightmare that circulated and through pastiches of his arresting scene. By 1790, he was elected a full academician, in 1799 he was made professor of painting and, soon after, keeper of the RA. Not such a nightmare after all, then, for an artist who originally fled his native land after a bust-up with a powerful and vengeful family.

A different kind of terror fills Peter Paul Rubens’s Samson and Delilah. Many artists have been drawn to the Old Testament story in which Samson is literally cut off from his superhuman strength when the scissors are taken to the source of his powers—his hair. In Rubens’s sumptuous painting of 1609, this vast muscleman has crashed out in Delilah’s lap, his visible left hand limp, as, above him, busy fingers snip at his curly locks. Thus enfeebled, he will be quickly captured by the Philistine soldiers waiting in the doorway.

Of course, sleep doesn’t only come to Biblical men or maidens in white frocks cut on the bias. Sheer exhaustion after a morning in the fields fells the man and woman who drop their sickles, kick off their clogs and flop down on the straw in Jean-François Millet’s Noonday Rest, from a series entitled ‘Four Times of Day’. As a student, John Singer Sargent took up the theme, echoing Millet in a sketch, and, in 1890, the last year of his short life, Vincent van Gogh also looked back at the French painter, but imbuing his own version of the couple with an almost liquid relaxation and investing in the countryside his distinctive restless movement. Van Gogh’s psychiatrist in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, a pioneer of art therapy, allocated his gifted and prolific patient not one, but three rooms: one for work, one as a store and one for rest. The doctor knew that work and sleep should not happen in the same place. Anyone condemned to work from home in a small flat would know he had a point.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Conversely, the languid subject of Flaming June doesn’t look as if she has ever done a hand’s turn in her comfortable life. She’s curled up cat-like against a sunlit Mediterranean backdrop, opulent oleander cascading over the parapet on which she leans, and her sleep appears to be born out of indolence rather than industry (although Frederic, Lord Leighton said the painting was ‘based on the chance attitude of a weary model at the end of a day’s work’), to be observed with envy, irritation or desire, depending on your point of view. Her diaphanous gown burns the retina; Leighton, who painted it towards the end of his life, admitted to a ‘fanatic preference for colour’. More fabric frames the sleeping beauty: a gauze in old gold and beneath that yet more sumptuous silk, of deepest crimson. This is the life, you may think—but perhaps not for long (the poisonous oleander suggests eternal rest). The picture’s own story is, by contrast, hectic, involving many changes of hands, its loss, rediscovery and final place in the founding collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico.

Flaming June’s luxurious subject may be droopy, but at least she is not drunk. The Dutch Golden Age artist Jan Steen leaves viewers in no doubt about what knocks out the snoozing men and women in his many scenes of low life. Giveaway empty flagons and mocking onlookers signal that drink has been taken, indecorously. To this day, a chaotic domestic life in the Netherlands is referred to as ‘a Jan Steen household’.

Although Steen’s coarse subjects are dead drunk, they are, presumably, still alive, yet parallels between death and sleep are often drawn and the states are ambiguous. In Sir Luke Fildes’s The Doctor (1891), it is unclear whether the sick child has turned the corner or is dying. Most powerfully, the infant Christ is often shown supported by his mother in a pose that prefigures his death.

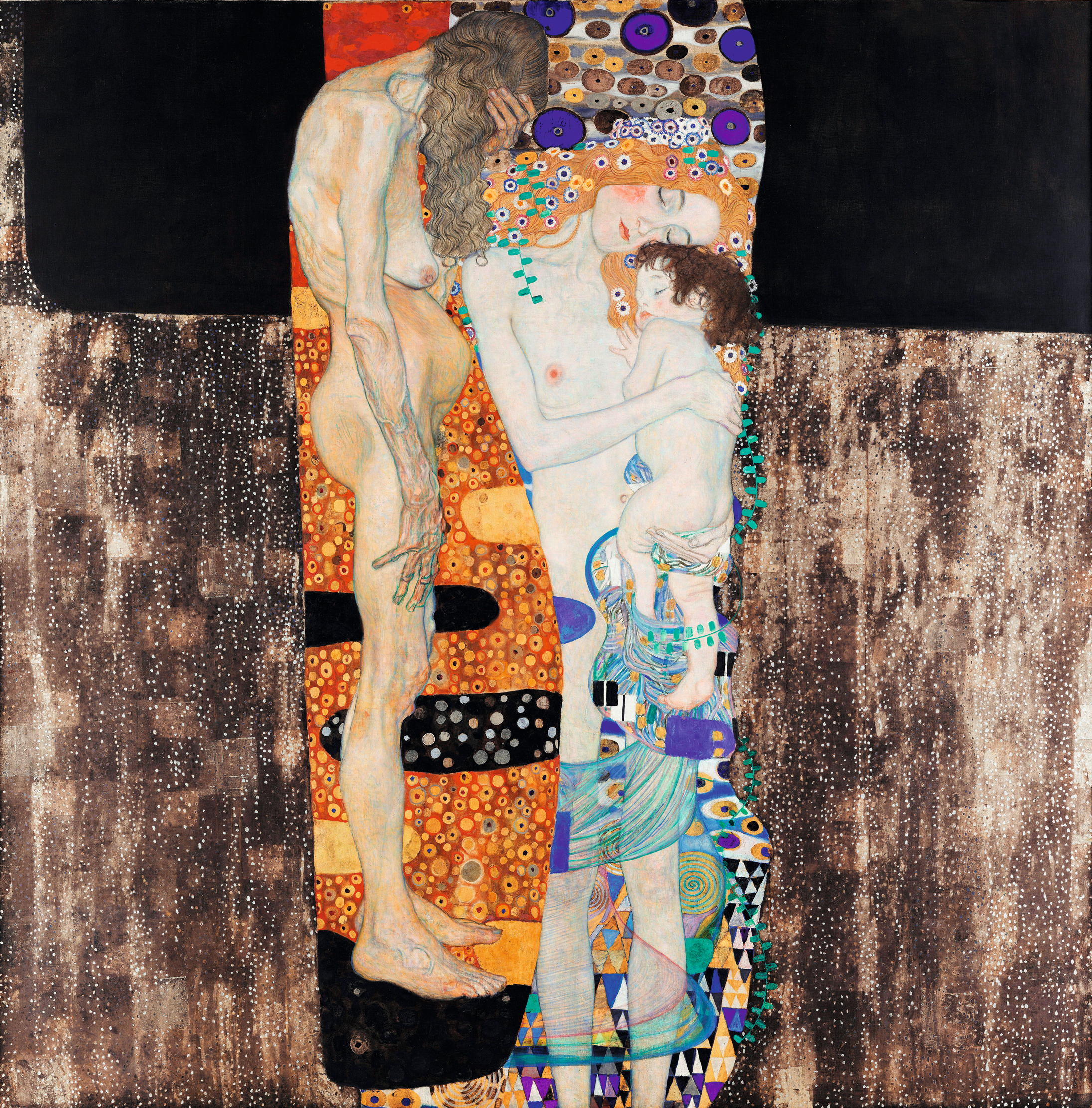

Botticelli and Giovanni Bellini are among the masters whose sleeping babies make us feel both affectionate and anxious. Other newborns are thankfully less complex: the proud parent watches the sleeping infant with contentment in Berthe Morisot’s Cradle (1872) and in Joaquín Sorolla’s Mother (1895), and the tiny girl dozing in Gustav Klimt’s Three Ages of Woman (1905) will, with luck, grow to be first a mother herself and then a grandmother, albeit one that seems to have been dealt a cruel hand.

The young woman in Klimt’s painting looks contented, yet seductive. There is an undertow of sexual longing or satisfaction in many depictions of female sleepers — images of Picasso’s young lover Marie-Thérèse Walter are particularly erotic — but some artists turn the tables. Botticelli’s wide-awake Venus looks distinctly put out by the sated Mars’s snooze.

It took a sculptor, Henry Moore, to celebrate and memorialise ordinary sleep. His real-life Londoners, sheltering from the Blitz, crammed together uncomfortably for a night in the Underground, are neither prophets nor strong men or gods. Yet, in his atmospheric wartime sketches, with their weary heads thrown back and their mouths agape, they are literally unconscious of their bravery, hero sleepers around the clock.

The foundry where Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Nic Fiddian-Green cast their bronzes

One of the oldest foundries in the world, Morris Singer in Hampshire has a long and storied past, creating art

Henry Moore: The sculptor who achieved the impossible

Henry Moore achieved international fame as a sculptor, despite once being denounced for promoting ‘the cult of ugliness'. And he

-

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comeback

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comebackPlum Cottage in Padstow, Cornwall, has been brought to life by Jess Alken and her husband, Ash — and is the latest addition to their holiday cottages on the north Cornish coast.

-

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few others

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few othersIt's the weekend which means it's time to kick back and make yourself an ice cold martini — courtesy of The Connaught Bar.