Exhibition review: Yves Saint Laurent in Co Durham

A cut above the rest.

Yves Saint Laurent once declared that, if he could have been born anyone else, it would have been Marcel Proust. Yet, unlike his hero, the fashion designer (1936–2008) produced an astounding and varied output. The Fondation Pierre Bergé, which he founded with his business and civil partner Pierre Bergé when he retired in 2002, holds 5,000 different outfits and 15,000 accessories, produced over a 40-year career.

Born in Oran, Algeria, the young Yves Mathieu-Saint-Laurent went to Paris to learn fashion design, encouraged by the editor of French Vogue, to whom he’d sent designs. Enigmatic, intelligent, and shy, he began work for Christian Dior at 17. At Dior’s unexpected death in 1957, aged just 52, Saint Laurent (his triple-barrelled surname now shortened) was declared Dior’s successor, despite being only 21.

In 1958, his second collection, in aid of the Red Cross, was shown at Blenheim Palace in front of Princess Margaret. It was a huge test for a very young designer now running the most important couture house in the world. Although there was a distinct Dior flavour in terms of formality and overall line, the seeds of individuality that would lead to his being fired two years later were already there.

The skirt of the shocking-pink Zéphirine dress, the star of that show, was experimentally cut, a cross between a 1750s Court dress, an 1850s crinoline and Dior’s New Look shape. Remark-ably, during research for the exhibition, this slightly sub-versive dress was discovered in the Palais Galliera museum in Paris, and goes on display for the first time ever, along with archive film of that glamorous 1958 occasion.

Perhaps the Blenheim setting influenced the decision to put Saint Laurent’s first major UK exhibition in a romantic Second-Empire French-designed château on a hilltop in Co Durham, rather than in the V&A in London. This bold move, given that the mus-eum’s local town, Barnard Castle, has only 5,000 inhabitants, brings an important exhibition to the North and to a museum whose star holding is its collection of historic clothing.

The magical Bowes museum was built by John Bowes, illegi-timate son of the 10th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, for his French wife, Joséphine.

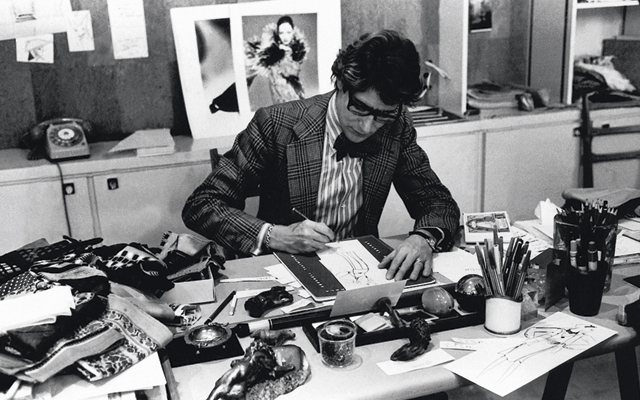

Saint Laurent’s oeuvre is well documented in this intelligent exhibition of 54 immaculate outfits, plus detailed working drawings, sample boards, accessories and films. A fascinating side room re-creates the designer’s atelier, with tailored cream canvas toiles, boxes of hundreds of buttons and embroidery samples, conveying the minute attention to detail in haute couture.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

One film shows the maestro retie a sash until it’s exactly right. He missed nothing; it set him apart. Two things made Saint Laurent exceptional: cut and insistence on femininity. His cutters had to be able to do tailoring, which informed his precision of line whatever style and shape, from spectacular to simple. During four decades, until he retired six years before his death, he presented a succession of hits that had a definite effect on European fashion as a whole.

Among those, one could pick out the 1965 Mondrian collect-ion that flashed around the world on magazine fronts or the 1988 Braques collection. The androgynous 1968 safari suit and 1962 pea coat also came to epitomise ‘YSL’ style and shape fashion even today.

His other strength was conferring unfailing femininity perhaps his greatest quality of all. Whatever he designed always enhanced the female body. From a sheer black-chiffon dress trimmed with lush ostrich in a sort of sensual parody of Josephine Baker’s notorious banana outfit to his now famous tuxedo jacket (called Le Smoking), women were always chic, not cheap.

His 18th-century-style yellow domino cloak would make anyone feel romantic as it billowed and sashayed behind as it did on the catwalk in 1983, later modelled by Carla Bruni-Sarkozy. Such is not always the case with modern design, but Saint Laurent never forgot that he designed for women and that he must always enhance their beauty.

As he famously said: ‘The most beautiful clothes that can dress a woman are the arms of the man she loves. But for those who haven’t had the fortune of finding this happiness, I am there.’

‘Yves Saint Laurent: Style is Eternal’ is at the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, Teesdale, Co Durham, until October 25 (01833 690606; www.thebowesmuseum.org.uk)

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day blows smoke, tells the time and more.

By Toby Keel

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon