Exhibition review: Homage to Manet at Norwich Castle

Matthew Sturgis explores how Manet influenced a band of British artists.

Virginia Woolf considered that the year 1910 marked a climacteric in British life. In her memorable formulation: ‘On or about December 1910, human character changed… The change was not sudden and definite… But a change there was, nevertheless; and, since one must be arbitrary, let us date it about the year 1910.’

One of the key factors contributing to this shift towards a distinctly modern sensibility was, she suggested, an exhibition of paintings held that year in London and curated by her friend Roger Fry. It was called ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’. And it created a sensation. Crowds came to be shocked, alarmed, amazed and sometimes even impressed. The exhibition included works by Matisse, Picasso and Vlaminck and also by Édouard Manet.

Manet might seem an unlikely addition to the list. He had, after all, died way back in 1883, after a short, bright, but always controversial career. He was essentially a ‘pre’ Impressionist and yet, still, in 1910, the freshness of his vision had the power to arrest attention and confound conventional expectations. This, of course, says much about conventional British expectations at the beginning of the 20th century and also about the slow acceptance of ‘modern’ French art in this country.

But an excellent new exhibition at the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, ‘Homage to Manet’, fills out this picture in new and interesting ways. It makes clear that, although the great British public may have been largely unaware of Manet even in 1910, a select handful of innovative British artists had long been conscious of his work and his genius and had in various different ways been adapting his lessons to their own practice. During the last years of the 19th century and the first of the 20th, these artists represented a daring, and often disparaged, avantgarde.

Two of these ‘British’ pioneers were, in fact, Americans. James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent had both come to know Manet personally and well during time spent studying in Paris and they brought their insights with them when they later settled in London. Walter Sickert never quite met Manet, although, as a young man, he heard his voice through a half-opened door when he called on the artist shortly before his death.

He did, however, know Manet’s art and helped relay that knowledge to London confrères such as Philip Wilson Steer and Henry Tonks at the recently formed New English Art Club. (Photo-graphs of Manet’s work were shown at the club’s early exhibitions.) What, however, were the elements of Manet’s art that so excited and inspired this younger generation of artists? We are in the happy position of being able to get a good sense of these.

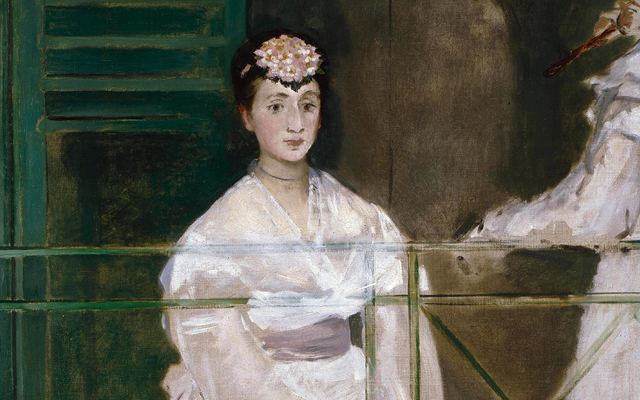

The exhibition at Norwich has, as its star attraction, Manet’s wonderful Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus, done in 1868 (and recently acquired by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, from whence it has been borrowed for this show). The white-clad, dark-haired young woman sitting on her green balcony distills many of Manet’s distinctive traits in a single, shimmering, work.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There is the technical bravura of his freely worked, almost sketchy, painting style. There is his delight in pure colour. There is his sense of engagement with the modern world of contemporary people in contemporary urban settings. There is the paradoxical blend of the intimate and the objective, the personal and the aloof. And there is his fascination with depicting the female figure.

The exhibition takes its title from Sir William Orpen’s self-consciously historical painting, Homage to Manet (included in the show), which depicts an informal gathering of forward-thinking British art-worthies Sickert, Tonks, Steer, D. S. MacColl, the critic George Moore and the collector Sir Hugh Lane beneath Manet’s portrait of the artist Eva Gonzalès, and suggests the lines of connection and influence that flow from the painting (then recently acquired by Lane for his gallery of modern art in Dublin) to the figures below. The actual presence of Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus in this exhibition plays the same role as the virtual presence of Gonzalès in Orpen’s painting.

Each and all of the elements in Manet’s picture find an echo in the work of his younger British admirers exhibited here transferred to British settings, filtered through personal styles and particular preferences. It is there in Sargent’s boldly slashing brushwork and in the intense objectivity of Sickert’s gaze.

It can also be felt in the intimate informality of Steer’s Two Girls Resting on the Grass. This delightful loosely worked painting, from about 1900, is one of the happy revelations of the exhibition. Only recently presented to the Norwich museum from a private collection, via the Art Fund, it was hitherto unknown and unseen. It provides another very good reason for heading east.

‘Homage to Manet’ is at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Castle Hill, Norwich, until April 19 (01603 495897; www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk)

Manet saved for the nation

The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has saved Edouard Manet's Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus for the nation after a fundraising campaign

Exhibition review: 'Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends' in London

Matthew Dennison is dazzled by an array of paintings by John Singer Sargent depicting his friends.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Athena: We need to get serious about saving our museums

Athena: We need to get serious about saving our museumsThe government announced that museums ‘can now apply for £20 million of funding to invest in their future’ last week. But will this be enough?

By Country Life

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel