Exhibition review: Eric Ravilious at Dulwich Picture Gallery

Peyton Skipworth assesses the work and vision of one of the most revered artists of the inter-World War years.

The new exhibition of watercolours by Eric Ravilious (1903–42) at the Dulwich Picture Gallery promises to be one of this summer’s most popular attractions. A dozen years ago, when the Imperial War Museum mounted the last show of Ravilious’s work to celebrate his centenary, he was still a little-known figure with people struggling to pronounce his name. Today, he is one of the most revered British artists of the inter-war years. What has changed and what is it about his work that makes it so beguiling and also so modern?

It’s easy to be bewitched by Ravilious’s magical handling of watercolour and his mastery of pattern-making, but hard to put one’s finger on the defining quality that makes his work unique; his use of dry, dragged paint, the dots and flecks, his use of wax-resist and scratching out are all magical, but it’s the sense of ‘otherness’, perhaps, that sets it apart and is its most enduring quality.

Aside from his time as an Official War Artist, represented by works such as HMS Ark Royal In Action and HMS Glorious in the Arctic and his series of lithographs of sub-marine interiors, his subject matter could, on the surface, appear somewhat mundane — beached boats at Aldeburgh, the South Downs in winter, cottage bedrooms in Wales and France, a post van in a bleak Wiltshire lane and pots of carnations and geraniums in a greenhouse — yet, somehow, his vision imbues the ordinary with a touch of the sublime.

Of course, any artist working in the 1930s was aware of Surrealism and Ravilious’s work often has a surreal quality — as in Ship’s Screw on a Railway Truck or the juxtaposition of the Westbury White Horse with a goods train steaming placidly through the valley below — but Surrealism was a self-conscious intellectual exercise, whereas Ravilious, with his eye for the quirky, was looking at Nature and real objects.

His love of the South Downs and downland chalk figures — the Westbury White Horse, the Long Man of Wilmington and the Cerne Abbas Giant among them — gives us some clue to his inner self and it was no accident that Gilbert White and H. J. Massingham were among his favourite authors. In his essay on Maiden Castle, Massingham wrote of being ‘sensitive to the peculiar effluence of places dyed in human associations’, noting elsewhere that: ‘It was man who had scarred the hills and so caused them to be clothed in beauty.’ Ravilious, who was himself a little detached from the world, was in tune with such sentiments.

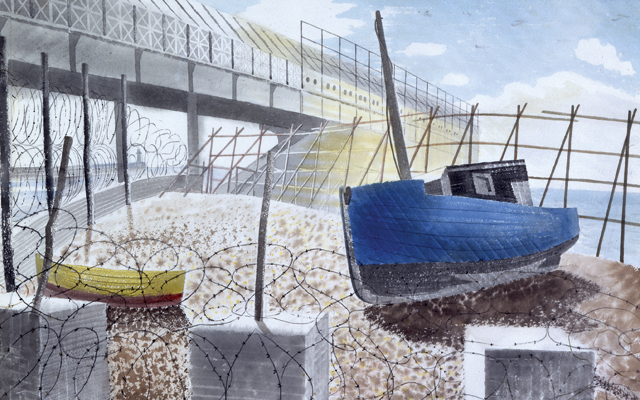

Most artists would have carefully avoided the tangled barbed-wire fences that mar the downland landscape and spoil the beaches, but, to him, they were part of the beauty of their clothing, a quality subtly emphasised early in this exhibition by the juxtaposition of two works: Anchor and Boats, Rye (1938) and the undated wartime South Coast Beach (1939–42).

War-time coastal defences had disfigured the beach in the latter with concrete blocks and barbed wire, but, several years earlier, he had striven to achieve the same effect scarring the beach at Rye with detritus — an old bicycle wheel, an abandoned anchor, chains and a battered tin tub.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As to ‘the effluence of places dyed in human associations’, his world was littered with such emanations: a wrecked Talbot-Darracq in a yard in Great Bardfield, a church army caravan at Castle Hedingham and a rusting roller in a frosty field on the downs are all witnesses of human association — it just needed Ravilious’s eye to spot and define their strange beauty. The genius loci of his world, unlike that of his erstwhile mentor Paul Nash, was fey rather than spiritual.

The excellently illustrated accompanying book by the exhibition’s curator James Russell makes great play of the fact that the groupings in the exhibition — ‘Relics and Curiosities’, ‘Interiors’, ‘Figures and Forms’, ‘Darkness and Light’, ‘Changing Perspectives’ and so on — are thematic rather than chronological. Personally, I found this somewhat contrived, designed more to justify the spaces — Dulwich’s exhibition galleries are small — than to enlighten the visitor.

Why, for instance, are Iron-bridge Interior and Flowers on a Cottage Table in ‘Figures and Forms’ rather than ‘Interiors’? The latter section contains Train Landscape, Room at The Will-iam the Conqueror and Interior at Furlongs, which, like the magical Belle Tout Interior in the final room, ‘Darkness and Light’, are as much concerned with outdoors as in. But these are quibbles. Thematic or not, the hang is sensitive, making for stimulating juxtapositions in which the works really talk to each other, adding to the pleasure of a thoroughly joyful exhibition. ‘Ravilious’ is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Gallery Road, London SE21, until August 31 (020–8693 5254; www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk). ‘Ravilious: The Watercolours’ by James Russell is published by I. B. Tauris (£25)

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

About time: The fastest and slowest moving housing markets revealed

About time: The fastest and slowest moving housing markets revealedNew research by Zoopla has shown where it's easy to sell and where it will take quite a while to find a buyer.

By Annabel Dixon

-

Betty is the first dog to scale all of Scotland’s hundreds of mountains and hills

Betty is the first dog to scale all of Scotland’s hundreds of mountains and hillsFewer than 100 people have ever completed Betty's ‘full house’ of Scottish summits — and she was fuelled by more than 800 hard boiled eggs.

By Annunciata Elwes