Evelyn Dunbar: The Lost Works review

An exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester is an opportunity to see some relatively litle-known works relating to WW2 and the English countryside

By Peyton Skipwith

Evelyn Dunbar’s reputation has been gradually growing since the 2006 exhibition of her work at the St Barbe Museum & Art Gallery in Lymington and the publication of Gill Clarke’s monograph, Evelyn Dunbar: War and Country. In the intervening years, her 1933 mural, The Country Girl and the Pail of Milk, in what is now the Prendergast School for Girls at Brockley, has been listed, along with those by her mentor Charles Mahoney, and her large painting A Land Girl and the Bail Bull has had a good airing at Tate Britain.

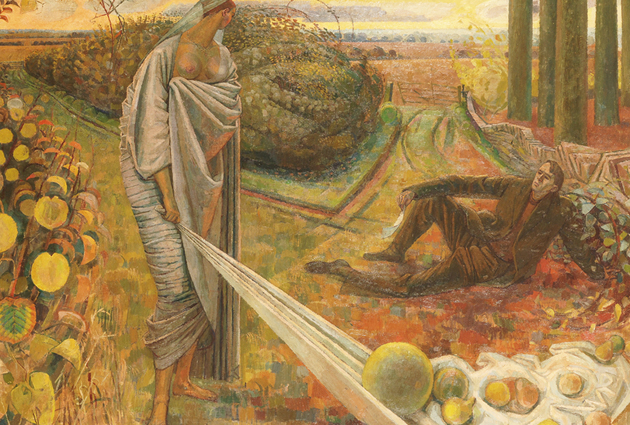

Dunbar (1906–60) was a pastoral painter with a strong poetic streak, as is immediately apparent in the new show, ‘Evelyn Dunbar: The Lost Works’. Upon entering the elegant early- 18th-century hall at Pallant House in Chichester, visitors are greeted by her impressive panel-like painting An English Calendar (1938), which depicts the months in human form with appropriate attributes, flanked by independent studies of February and April. These, along with her postwar Autumn and the Poet (above), which hangs on the opposite wall, immediately set the mood for the exhibition by declaring her passion for gardening and her delight in anthropomorphizing days of the week and seasons of the year.

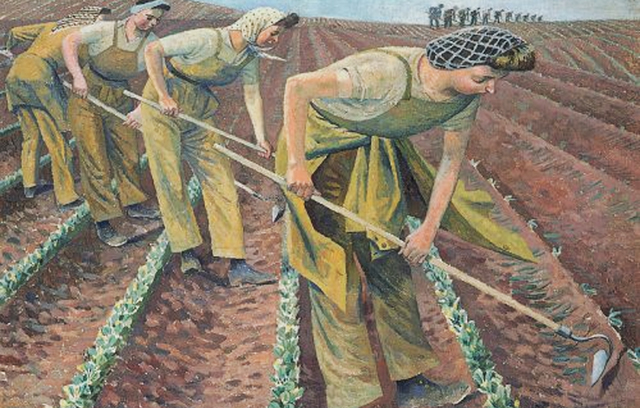

In April 1940, Dunbar was appointed Official War Artist with a brief to record the Women’s Land Army. Sadly, A Land Girl and the Bail Bull is not included in this exhibition, but other excellent smaller oils from this period are. Men Stooking and Girls Learning to Stook, Singling Turnips and a study for Milking Practice with Artificial Udders show her command and understanding of her brief.

Stooking has often been reproduced, but Singling Turnips, with its Spencerian rhythm of girls hoeing, was totally new to me. Dunbar’s admiration for Stanley Spencer’s vision emerges again in a delightful oil study, Flying Applepickers, painted at Long Compton in Warwickshire, the village to which she and her husband, Roger Folley, moved at the end of the war, before Dunbar’s appointment to Kent’s Wye College in 1950 (after her death, Folley gifted An English Calendar to the college). Gardening and plants were a shared obsession of the Dunbar family and a passion Evelyn shared with Mahoney in the 1930s, when their collaboration was at its closest.

Their joint work, Gardeners’ Choice, is a rare book, but, happily, it has now been republished by Persephone Books. So close was their affinity that it’s impossible to differentiate their work, but a good group from among the socalled ‘Lost Works’, presumably by Dunbar, are included in the show.

It seems necessary these days to give exhibitions a punchy—and often meaningless—subtitle. The substantial cache of Dunbar’s work that came to light recently, and which forms the core of this exhibition, was never lost. It was given by Folley to Dunbar’s younger brother after her death and remained in the family undisturbed until her large work, Autumn and the Poet, which now belongs to Maidstone Museum, turned up on Antiques Road Show a few years ago.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The art dealer Andrew Sim, a long-time admirer of Dunbar’s work, has just produced his annual catalogue of Second World War art, Holding the Line. It includes the Folleys’ 1953 Christmas card, which bears an intriguing resemblance to The 34 Gallery, an extended model of a contemporaryart gallery with miniature paintings and sculpture by Vanessa Bell, Frank Dobson et al. Dunbar could easily have seen the model when it was first exhibited, in 1934, at Chesterfield House in London; it now resides in Pallant House Gallery’s permanent collection. Mr Sim has gathered together a wide-ranging group of works for sale, although, bizarrely, he details the mediums, but not the measurements. They range from Mary Eastman’s jolly portrait of Cherry Brown in her Land Army uniform to Felix Topolski’s gruesome Germany Defeated.

The mood of the other works illustrated in his catalogue covers the whole spectrum, from the optimistically patriotic scene of crowds cheering outside Buckingham Palace by Leonard Fuller, presumably painted after Chamberlain’s return from Munich, to the chillingly cold Belsen: Burning the Horror Camp by Edgar Ainsworth, former art editor of Picture Post.

Three spirited drawings by the 94-year-old Colin Scott-Kestin, oneof the few surviving artists from the period, are of considerable interest. His two pen, ink and watercolour studies of Felixstowe Harbour, somewhat in the manner of James McBey, deserve to find a permanent home in the town.

‘Evelyn Dunbar: The Lost Works’ is at Pallant House Gallery, 9, North Pallant, Chichester, until February 14, 2016 (01243 774557; www.pallant.org.uk). For viewing by appointment at Sim Fine Art, email simfineart@btinternet.com.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passions

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passionsVincent Zanardi reveals the present from his grandfather that he'd never sell and his most memorable meal.

By Rosie Paterson

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson