The Englishman who made Canaletto famous, and the paintings he kept for himself

Canaletto is the focus of a new exhibition at Buckingham Palace that is based on the collection of one of the artist's most important patrons. Huon Mallalieu delights at the artist's imaginative reality.

Royal Collection Trust/(c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

For single use only in connection with the exhibition 'Canaletto & the Art of Venice' at The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, 19 May - 12 November 2017. Not to be archived or sold on.

Joseph Smith was an ideal consul: both the country he represented and that to which he was accredited benefited greatly by his activities. Having arrived in Venice at the very start of the 18th century, aged 19, he rose to be senior partner of a trading and merchant-banking house and, from 1743/4 to 1760, British Consul.

Horace Walpole sneeringly referred to him as ‘the merchant of Venice’, who knew only the title pages of the lavish limited-edition books he had printed, but the sneer was unjustified. His beautiful and accurate edition of Palladio’s Quattro Libri so pleased Goethe that he visited the Lido to pay tribute at Smith’s grave, and his patronage of the painters Canaletto (aka Giovanni Antonio Canal) and Zuccarelli can be said to have created the 18th-century British country-house interior.

As well as building up his own collection of paintings, drawings and prints and amassing a formidable library, Smith acted as agent for his favoured artists – particularly Canaletto – introducing Grand Tourists to them and arranging commissions.

Canaletto (1697–1768) was the son of a scene painter and the training shows in his work. He was also taught by Luca Carlevarijs, the principal vedute (or view painter) of the day, whom he soon surpassed.

"This show delivers a heart-raising burst of Venetian sun without the need to go on a Grand Tour"

Already, in 1725, another agent urged a client to consider Canaletto’s work, as ‘it is like Carlevarijs, but you can see the sun shining in it’. Smith discovered him soon after and all who called on business, especially after he became Consul, would find themselves in a showroom of his art.

It was also Smith who encouraged Canaletto to go to England when the Seven Years’ War cut off the supply of Grand Tourists, providing him with introductions and suggesting profitable subjects such as capriccio paintings of British Palladian houses.

George III bought Smith’s collections en bloc in 1762. The books are now the essence of the King’s Library in the British Museum, but the wealth of paintings and drawings remain in the Royal Collection – and the new exhibition of Canalettos at The Queen’s Gallery in London puts those paintings in the spotlight.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Coming directly from Smith, the Canalettos on show in this dazzling exhibition are of particularly high quality. They are hung in pairs or groups as they would probably have been seen on the Grand Canal in the Palazzo Balbi (now Palazzo Mangilli-Valmarana), with its Palladian façade added for Smith by the architect-painter Visentini.

Six large Venetian canvases are grouped in pairs on one wall, another has a run of 12 smaller views constituting a conducted tour of the Grand Canal and a third is hung with large Roman views for variety. There are also capricci, in which the artist plays with disparate, but actual, buildings, combining them to artistic effect.

The next gallery is hung with Canaletto’s Venetian contemporaries, including Carlevarijs, Sebastiano and Marco Ricci, Piazzetta, Longhi, Visentini and Zuccarelli, and Rosalba Carriera’s lovely, if very sweet, pastels of the Four Seasons.

Thanks to Smith, Canaletto remains one of Britain’s favourite artists. We hardly notice that, when in England, he gives the Thames an Italian light, nor that his precise views of La Serenissima are not quite the exact portraits of his native city that they seem.

His training in theatrical painting lofts should not be forgotten, as it is not just in capricci that he readjusts views and details to suit his composition. That, however, is perhaps why he is much less highly regarded in Venice itself. It surprises many first-time visitors to find that, for much of its length, the Grand Canal is much narrower than he portrayed it.

The city was in irreversible decline by the time his career was at its zenith, especially after the Seven Years’ War, but Canaletto uses all his scene-painter’s skills to convey wealth and busyness. Bustle and urgency are suggested by the way that so many gondole, sandole and bragozze are cut off on the canvas edge as they dart into and out of shot, as it were. Figures are staffage, posed in repetitive, but effective groups and, especially in later works for which his studio was often partly responsible, rippled water is rendered by formulaic white squiggles.

None of these quibbles matters a jot. No matter what the summer holds for us, this show delivers a heart-raising burst of Venetian sun without the need to go on a Grand Tour.

- ‘Canaletto and the Art of Venice’ is at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London SW1, until November 12 – see www.royalcollection.org.uk for more details

Credit: Alamy

Two middle-aged ladies, one beautiful Fiat, and a magical week in Umbria

Mary Miers teamed up with an old friend as she visited one of Italy's most enchanting regions.

Eight perfect stop-offs for a wine tour of Italy

The experts from Decanter give their best ideas if you're considering a wine tour of Italy.

Credit: www.italianluxuryasset.com/

The perfect Tuscan villa? 6 beds, pool, and just over £300,000

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

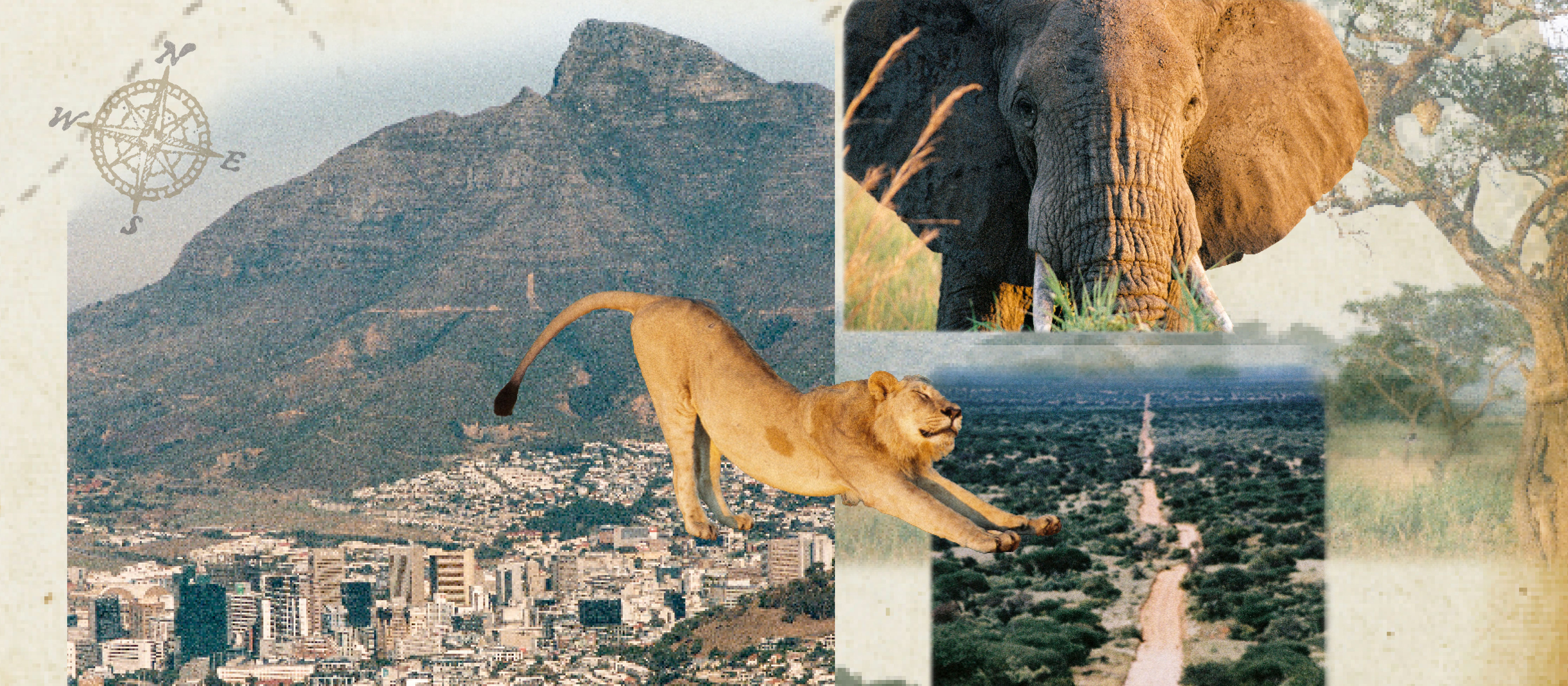

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to Cairo

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to CairoWhy do we travel and who inspires us to do so? Chris Wallace went in search of answers on his own epic journey the length of Africa.

By Christopher Wallace

-

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River Tay

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River TayCarnliath on the edge of Strathtay is a delightful family home set in sensational scenery.

By James Fisher

-

The best regional art galleries in Britain, from Cornwall to Orkney

The best regional art galleries in Britain, from Cornwall to OrkneyWherever you are in Britain, you’re never far from an interesting gallery. Here we present an eclectic round-up of 45 places to see art outside the big cities.

By Country Life

-

Cerne Abbas: Was the giant naked man an artistic act of defiance aimed at monks?

Cerne Abbas: Was the giant naked man an artistic act of defiance aimed at monks?New evidence suggests that the Cerne Abbas giant is much older than previously thought — and that its creation might have been 'a big two fingers' aimed at the Benedictine monks who had recently established an abbey.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Nine of the most astonishing objects you can see at National Trust properties, from priceless paintings to a wooden leg to a simple tunic with a heartbreaking tale to tell

Nine of the most astonishing objects you can see at National Trust properties, from priceless paintings to a wooden leg to a simple tunic with a heartbreaking tale to tellWe're taking a look at nine of the greatest objects on display in the National Trust's properties across Britain.

By Country Life

-

The Ickworth Velazquez that's one of the very greatest treasures of the National Trust

The Ickworth Velazquez that's one of the very greatest treasures of the National TrustIn the final part of our series looking at the National Trust's finest treasures, we look at one of the very finest paintings in the Trust's ownership.

By Country Life

-

A 15th-century altar cloth that survives in almost miraculous condition, one of the National Trust's greatest treaures

A 15th-century altar cloth that survives in almost miraculous condition, one of the National Trust's greatest treauresOur series looking at the National Trust's finest treasures looks at a pre-Reformation altar front from Cotehele which has survived to the present day.

By Country Life

-

A Chippendale table that's 'the epitome of light-hearted Chinoiserie design', one of the National Trust's greatest treasures

A Chippendale table that's 'the epitome of light-hearted Chinoiserie design', one of the National Trust's greatest treasuresOur series looking at the National Trust's finest treasures takes aim at the Thomas Chippendale dressing table of Anglesey Abbey in Cambridgeshire.

By Country Life

-

A pair of tureens that are a Rococo tour de force in silver, and among the finest treasures of the National Trust

A pair of tureens that are a Rococo tour de force in silver, and among the finest treasures of the National TrustWe're taking a look at nine of the greatest objects on display in the National Trust's properties across Britain — this time around we look at the incredibly intricate soup tureens of Ickworth.

By Country Life

-

A great Italian masterpiece brought to life as a woodcut by an English genius, one of the National Trust's finest treasures

A great Italian masterpiece brought to life as a woodcut by an English genius, one of the National Trust's finest treasuresWe're taking a look at nine of the greatest objects on display in the National Trust's properties across Britain — today it's the astonishing carving at Dunham Massey.

By Country Life