Curious Questions: Who created the 'Your Country Needs YOU' poster?

It's one of the most famous images of the 20th century, copied and parodied countless times. But who created the famous image of Lord Kitchener calling his countrymen to arms? Nicholas Hodge takes a look — and discovers a dog-loving cartoonist who'd 'rather win a medal at golf' than be elected to the Royal Academy.

It has been said that the ‘Your country needs you’ image of Lord Kitchener entreating men to join the British Army and fight in the First World War has entered our DNA. Certainly, if the field marshal’s moustache were to grow like Pinocchio’s nose every time a cartoonist parodied the 1914 poster, we would already be contending with a marvel the length of Hadrian’s Wall.

Harold Macmillan, David Cameron and Boris Johnson are only a few of the prime ministers to have fallen victim to the Kitchener treatment. Even sci-fi crusaders have got in on the game, with a gleaming Darth Vader stepping into Kitchener’s shoes in a Star Wars ‘Your empire needs you’ billboard.

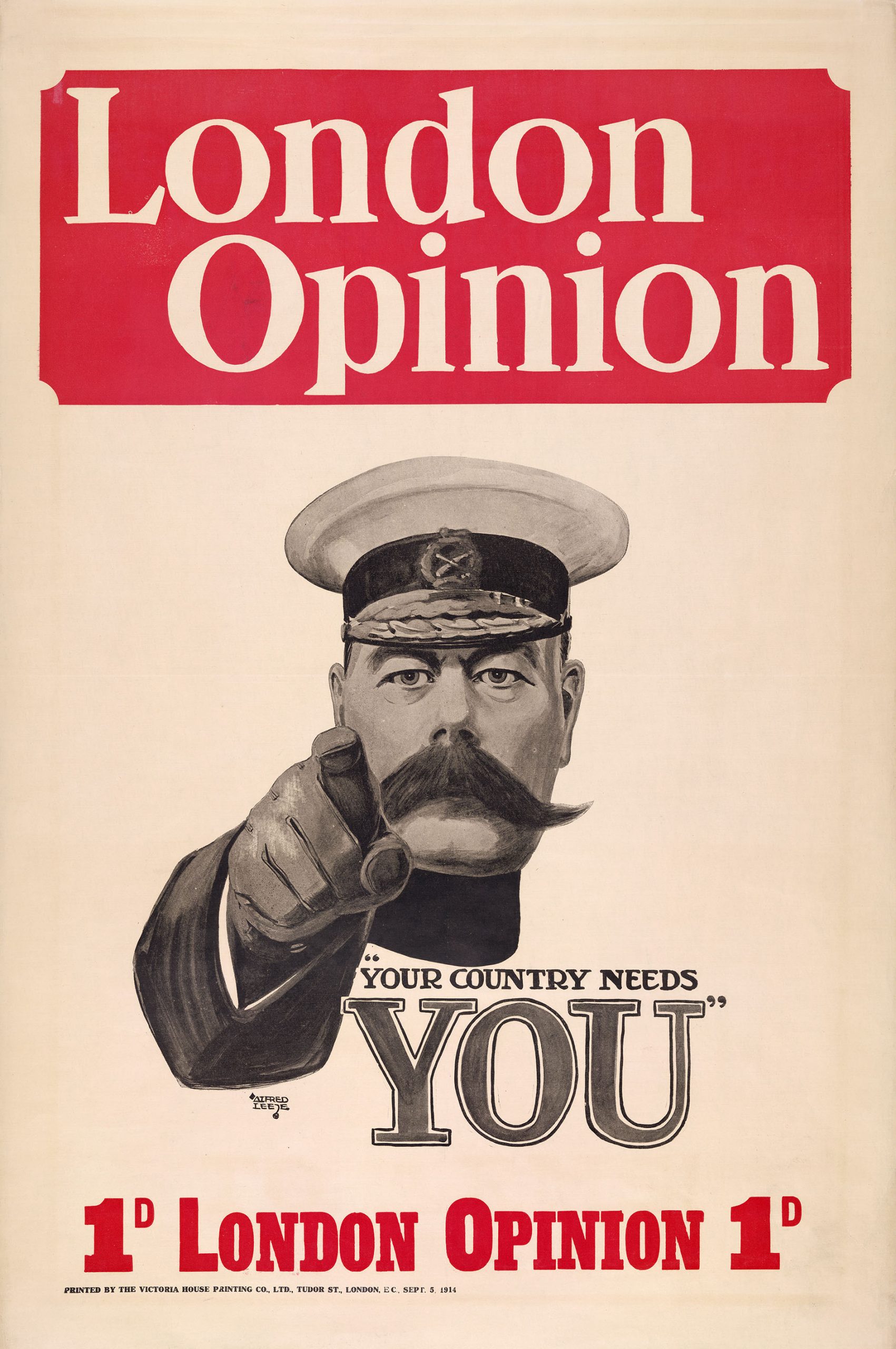

The man responsible for it was Alfred Leete — yet, curiously enough, the creator of this wartime advertisement never set out to design a recruitment poster. The picture was dashed off for the cover of popular weekly London Opinion in September 1914, apparently after the editor had vetoed another cartoonist’s efforts.

The magazine wanted something topical and recruitment was on everyone’s lips. Enter Leete, already an established contributor to the publication, who was rarely photographed without a pipe or cigarette in his mouth.

Eagle-eyed researchers Martyn Thatcher and Anthony Quinn have suggested in their book about the image that the iconic pointing finger may have been pinched from a cigarette advert. Either way, the image of Kitchener — the newly-installed Secretary of State for War — proved a hit and soon took on a life of its own.

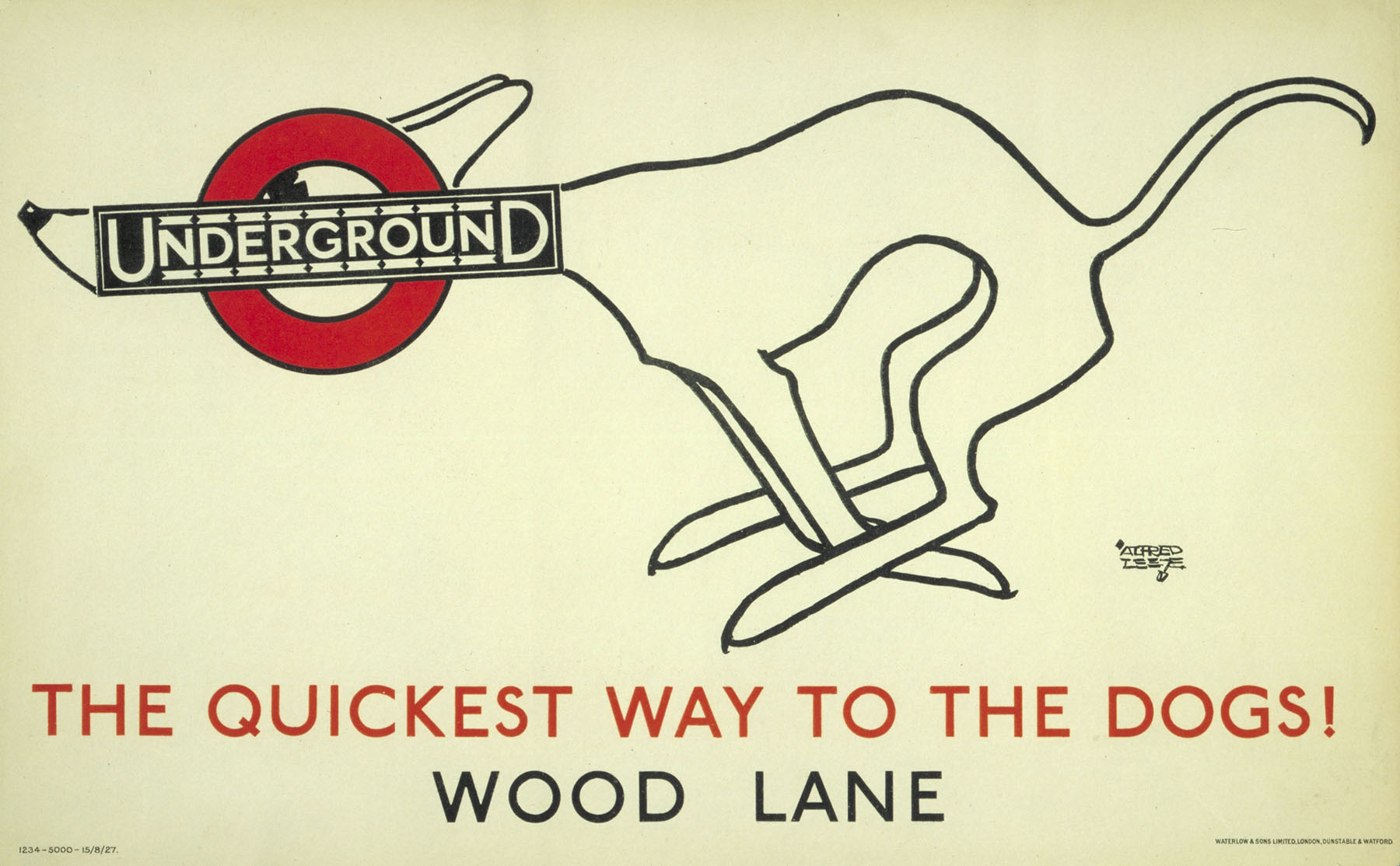

If he hadn't found fame for this poster, Leete might just as well be remembered as a painter of non-military subjects — not least four-legged ones. Of the half a dozen posters he designed for the London Underground, four feature dogs, either in the starring role or as scene-stealing extras.

In two of these, a greyhound signals the swiftest way to reach London’s dog-racing stadiums, aided in one by a wide-eyed rabbit. As with the uncluttered Kitchener design, Leete finds his mark by following the dictum that less is more.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

His canine heroes were not confined to posters, either. They trotted into magazines such as Tatler, The Sketch and The Bystander. He was also the first British artist to take on P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves stories, together with illustrations for many other tales by the comic master. Leafing through old editions of The Strand — for which he juggled several authors, as well as Wodehouse — reveals the artist inserting dogs in the most unlikely of places, with one hovering over a casino in the south of France.

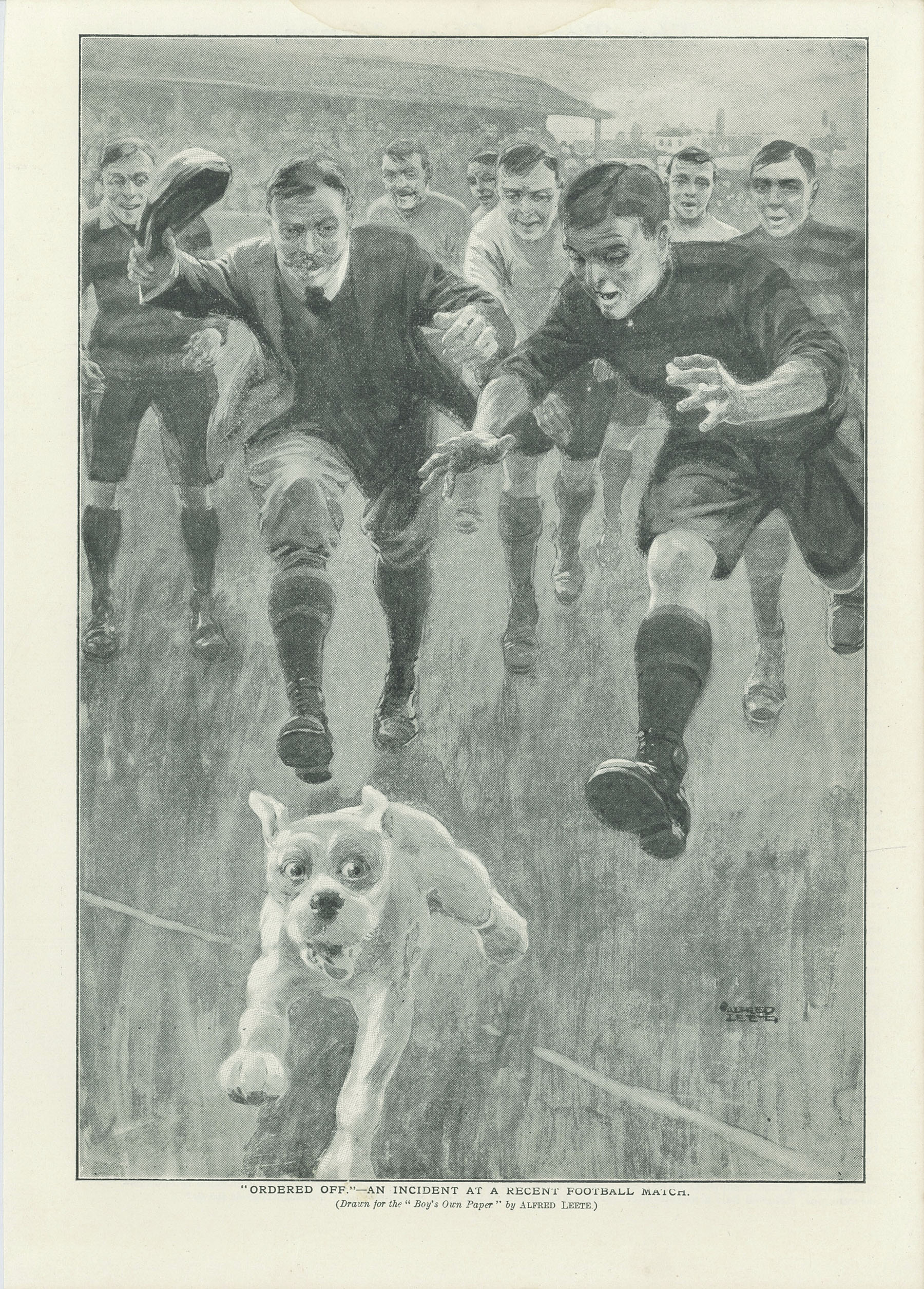

Echoing Wodehouse, Leete was, above all, focused on entertainment. He once quipped that he’d ‘rather win a medal at golf’ than be elected a Royal Academician. Still, he clearly knew his art history. Today, if something bizarre happens at a football match, legions of photographers will be poised to capture the moment, armed to the teeth with zoom lenses.

Before the First World War, it was down to artists to conjure such incidents. When a dog gallivanted across the pitch during the 1910 season, Leete was on hand to deliver the goods. His take on the canine fugitive has all the drama of a Baroque painting. I feel sure that if Caravaggio had ever painted a dog being chased off a football pitch, this is how he would have done it, not least because Leete plainly spent his days off prowling round The National Gallery.

Alfred Ambrose Chew Leete was born in 1882, in Thorpe Achurch, Northamptonshire. His father was a farmer and the first known photo of Leete finds him sitting astride a rocking horse, with a cocker spaniel standing guard. As his father’s health was shaky, a plan was hatched to move to the coast, with hopes that the sea breeze would weave its magic.

The leap was made in 1893 and, before long, the duo was running two sizeable hotels in Weston-super-Mare, at the time taking off as a holiday destination. At the age of 12, with Leete’s drawing talent coming to the fore, it was decided that he should be apprenticed to an architect. Although his heart was never really in it, the job helped him fine tune his grasp of perspective. His first cartoon was published in The Daily Graphic in 1897 and London beckoned.

Fleet Street proved a hard nut to crack, but humour was on his side. Editor William Comyns Beaumont, who knew the artist during the early London days, recalled: ‘When I first knew Alfred Leete, he pointed a joke at himself by plastering his studio with “Editor regrets” slips, of which he had received a vast quantity.’

A key break came in 1905, when his first sketch for Punch was printed. It was the start of a long-running collaboration, during a fertile time for cartoonists and caricaturists. ‘At the beginning of the 20th century, in an age before television, cinema or radio, they were held in high regard — as social commentators and witty graphic journalists they were seen as important members of the media and suitably rewarded by their employees,’ notes Mark Bryant, in his Dictionary of 20th Century British Cartoonists and Caricaturists.

When war broke out in 1914, Leete was already a firmly established player, rustling up covers for several weeklies. It was a time when ‘spy fever’ gripped the nation and he defused some of this anxiety with a series of cartoons about a bumbling, ‘almost loveable’ German agent called Schmidt. Once again, dogs abounded. Schmidt proved such a success that the saga was turned into a movie.

As historian James Taylor has shown in his eye-opening book Pack up Your Troubles: How Humorous Postcards Helped Win World War I, cartoons were considered potent weapons — so much so that the War Office was concerned that British prisoners of war caught with caricatures of the Kaiser might be shot.

When Leete and fellow cartoonist Bert Thomas were called up in 1917 — both joining the Artists Rifles — journalist Henry Simonis commented: ‘Heaven help them, if after their innumerable jests at the expense of the Kaiser and “Little Willie”, either of them should be taken prisoner.’ In fact, Leete was never sent over the top (he did mainly clerical work for the No. 15 Officer Cadet Battalion) and both men returned to civilian life in 1918.

Leete was much in demand over the coming decade. As well as his press work, he dished up posters for brands such as Bovril and Guinness and was invited to create mascots for the brewery William Younger and Rowntree’s chocolate. The latter, a top-hatted, cane-carrying character dubbed Mr York of York, Yorks., received fan mail from across the globe and may have planted a seed in the imagination of a schoolboy named Roald Dahl.

Comyns Beaumont noted that Leete was ‘as full of ideas as an egg has meat’, yet some promising characters disappeared almost as soon as they had got out of the starting blocks. A dapper elephant in a tailcoat, with its trunk in a twist, appeared in Dutch magazine Haagse Post several years before Babar. If only Leete had given him a longer run. The same goes for his surreal Cocktail Girl. Thankfully, he did let some characters find their feet. Dennys, ‘Rouge Dragon of the Fiery Breath’, immortalised in A Book of Dragons (1931), is one of his finest. The spaniel-sized protagonist, who seems more dog than dragon, was given a hero’s welcome in Weston-super-Mare, where a pub was christened The Dragon in his honour.

Leete died relatively young at 50 and, today, it’s the Kitchener poster for which he is chiefly remembered. However, given that he himself was the first to send it up — only two months after its appearance — it’s safe to say that ‘he would have been surprised and delighted in equal measure by the mind-boggling array of merchandise, including cufflinks, mugs and mobile-phone covers, it has spawned,’ as Mr Taylor notes.

Meanwhile, there are signs that Leete’s lesser-known creations are finding a new audience. In 2018, the cartoonist was commemorated with a plaque and an exhibition in Weston and devotees of his work hope that English Heritage may pick up the baton in London. His former Kensington home would seem ideal for such a tribute. Indeed, The P. G. Wodehouse Society, the House of Illustration, the London Sketch Club, the London Transport Museum, the Cartoon Museum and the Artists Rifles Association have all expressed enthusiasm for the idea. Dennys would heartily approve.

Alfred Leete’s life and times

1882 Born in Thorpe Achurch, Northamptonshire

1893 The Leetes move to Weston-super-Mare in Somerset

1897 The young Leete’s first cartoon is published in The Daily Graphic

1899 Leete moves to London

1905 He begins his collaboration with Punch

1909 Marries Edith Webb

1914 His Kitchener picture debuts on the cover of London Opinion

1917 Joins the Artists Rifles regiment

1918 Leete returns to civilian life

1921 Elected to the Savage Club, where fellow members include P. G. Wodehouse and Charlie Chaplin

1925 Contributes to the first edition of The New Yorker, on February 21, and is elected president of the London Sketch Club

1931 A Book of Dragons is published

1933 Dies at his London home, aged 50, and is buried in Weston-super-Mare

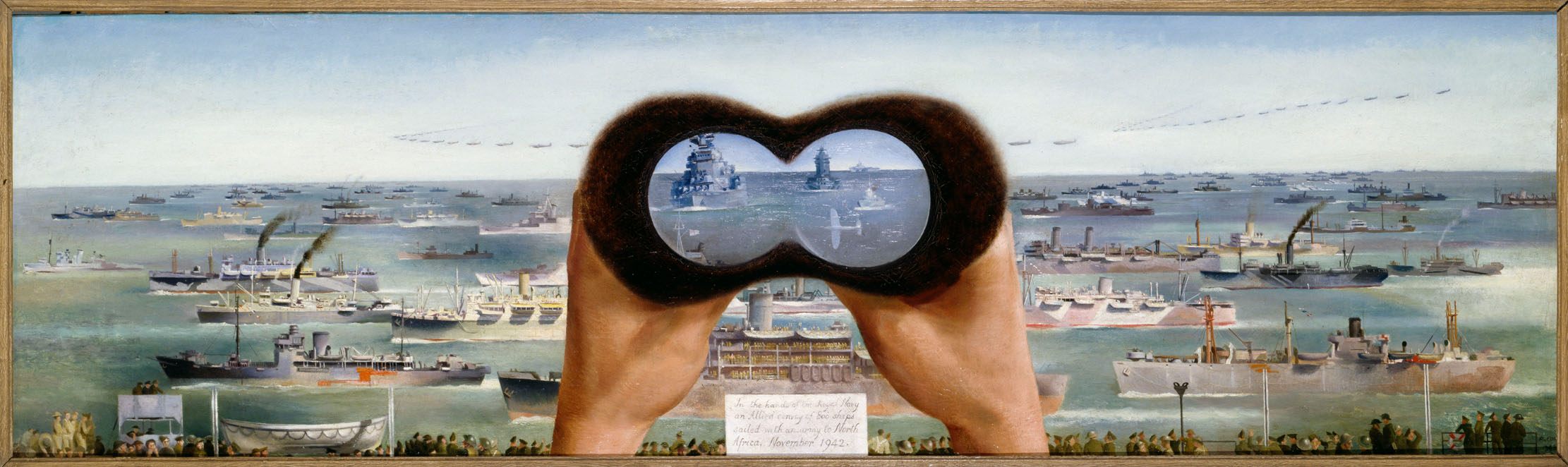

In Focus: The Anglo-German pacifist-turned-war artist who famously chronicled Dunkirk — despite not being there

Richard Eurich was a war artist, draughtsman and visionary painter of people, landscape and the sea. In this 80th anniversary

The unique and extraordinary images of the First World War created by Britain's first-ever official war artist

'There are some things that never will be reproduced if the world lives a million years': What it was like to be alive at the end of the First World War

They cheered, they cried, they laughed, they danced in the streets. Almost 100 years to the day since it was

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?It was the home of Mr Gruber and his antiques in the film, but in the real world, Alice's Antiques could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?The King's recent visit to Nansledan with the Prime Minister gives us a clue as to Labour's plans, but what are the benefits of traditional architecture? And can they solve a housing crisis?

By Lucy Denton

-

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the world

From fighting for stockings to flying on the Moon: How nylon changed the worldAlmost 90 years after it was first discovered, Martin Fone looks at the history of this mass produced man-made fibre.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?

Curious Questions: Why do woolly hats have bobbles?Some can rock a bobble hat, others will always resemble Where’s Wally, but the big question is why the bobbles are there in the first place. Harry Pearson finds out as he celebrates a knitted that creation belongs on every hat rack.

By Harry Pearson

-

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?

Curious Questions: We used to fly cars across the English Channel in 20 minutes — why did we stop?It seems hard to believe, but taking your car across the English Channel to France by air actually pre-dates the cross-channel car ferry. So how did it fall out of use almost 50 years ago? Martin Fone investigates.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?

Curious Questions: Who invented the rear-view mirror?Although obvious now, the rearview mirror wasn't really invented until the 1920s. Even then, it was mostly used for driving fast and avoiding the police.

By Martin Fone

-

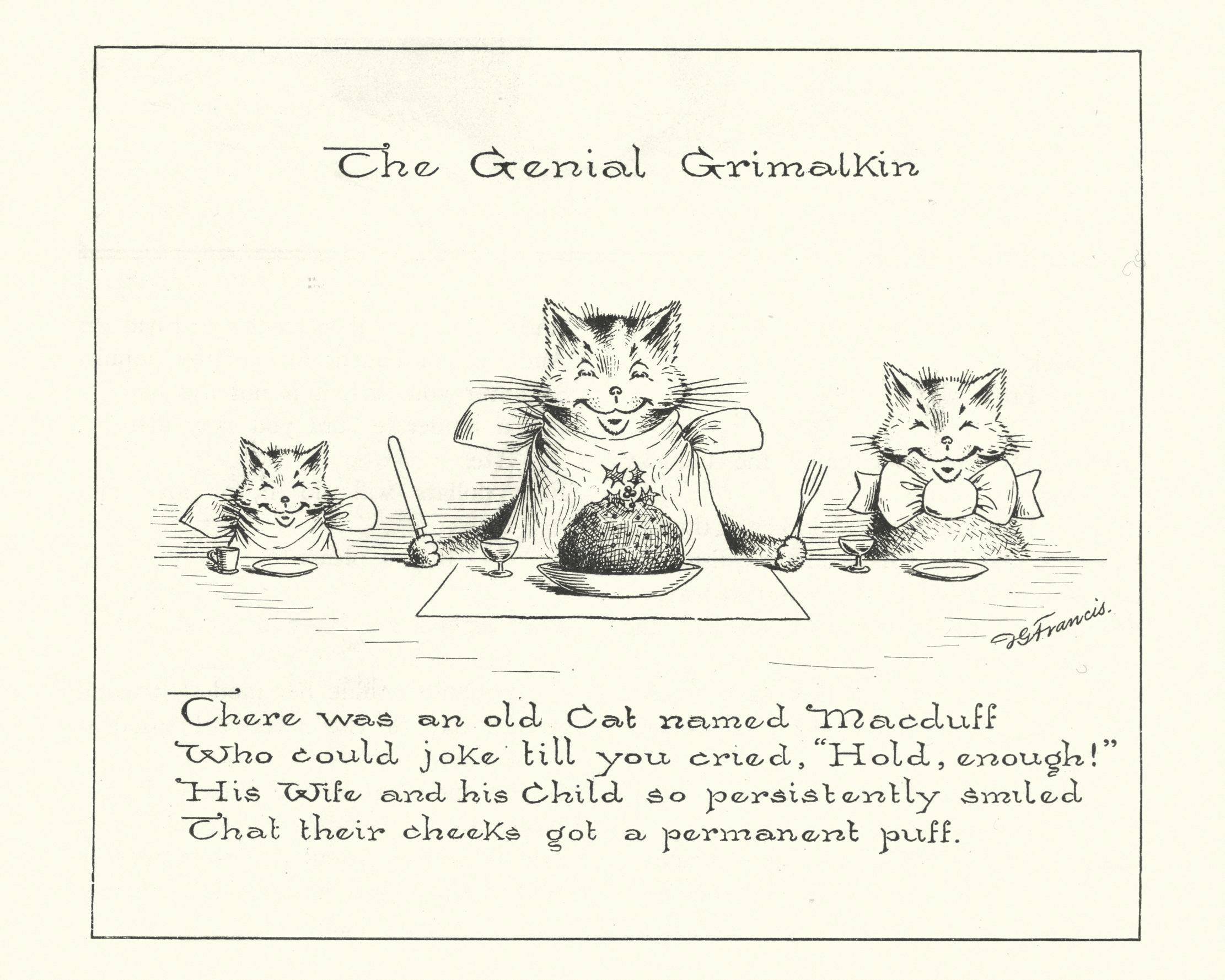

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?

Curious Question: Did the limerick originate in Limerick?Before workers wasted time scrolling Twitter or Instagram, they wasted their time writing limericks.

By Martin Fone

-

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal Household

You rang, your majesty? What it was like to be a servant in the Royal HouseholdTending the royal bottom might be considered one of the worst jobs in history, but a life in elite domestic service offered many opportunities for self-advancement, finds Susan Jenkins.

By Country Life

-

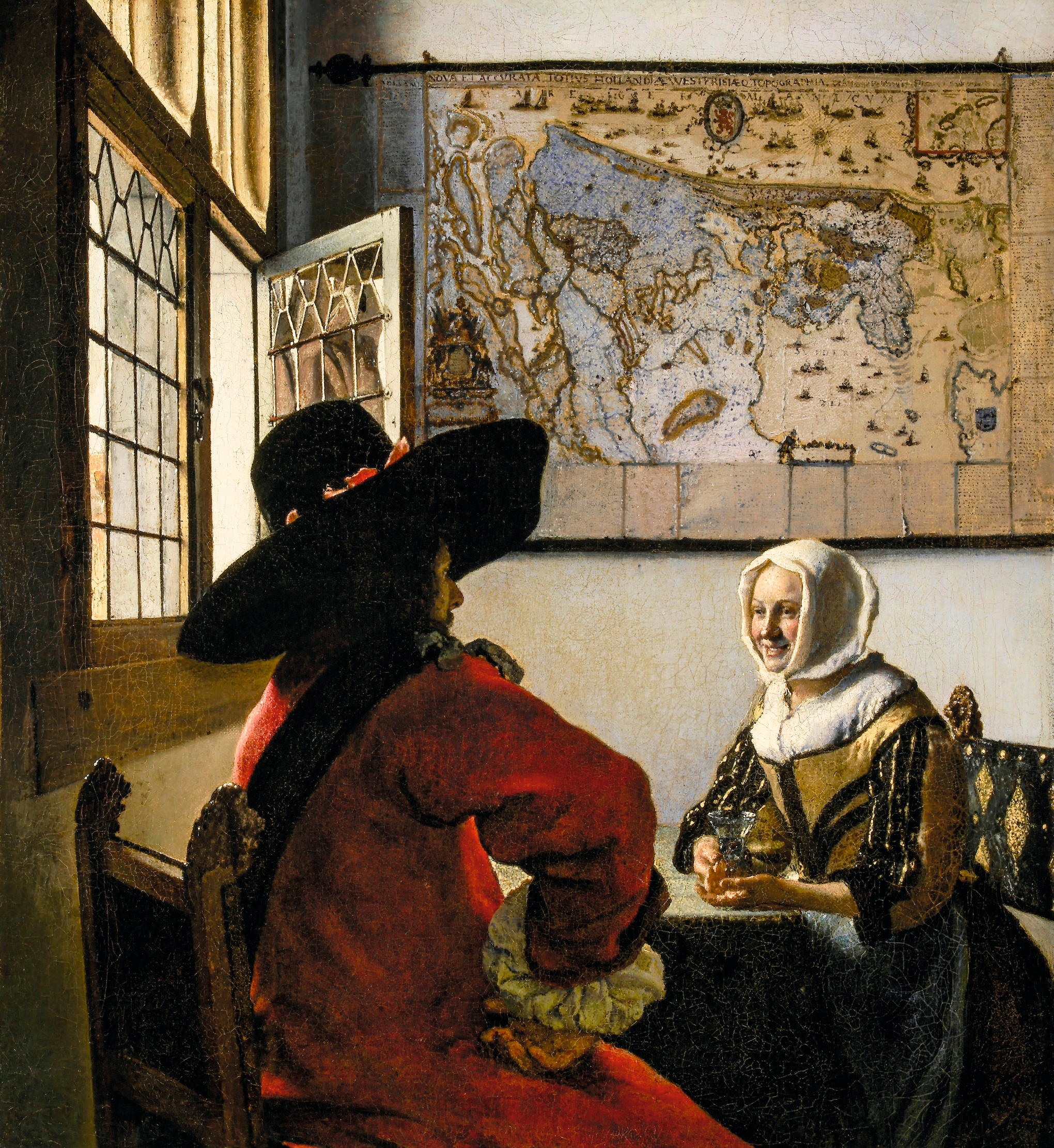

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?

Curious Questions: Why are there so few smiles in art?Centuries of portraits down the ages — and vanishingly few in which the subjects smile. Carla Passino delves into the reasons why, and discovers some fascinating answers.

By Carla Passino

-

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectors

Tanks, tulips and taxidermy: The strange lives of Britain's most eccentric collectorsFive collectors of unusual things, from taxidermy to tanks, tulips to teddies, explain their passions to Country Life. Interviews by Agnes Stamp, Tiffany Daneff, Kate Green and Octavia Pollock. Photographs by Millie Pilkington, Mark Williamson and Richard Cannon.

By Agnes Stamp