Curious Questions: What happened to saucy seaside postcards?

Saucy seaside postcards were once a mainstay of British life over the summer, but these days they're rarely seen. Martin Fone asks why, and discovers the history of artists such as Donald McGill who turned wry, naughty humour into a huge industry.

On July 15, 1954 a seventy-nine-year old man found himself in front of the magistrates in Lincoln charged with breaking the Obscene Publications Act (1857). How he got there sheds a fascinating light on British culture and moral attitudes.

In an age of instant communication, it is easy to forget that sending a postcard to friends and relatives was de rigueur for holidaymakers, used to inform them of a safe arrival and perhaps even wishing they were there. Postcards made their first appearance in Britain in 1870. They were plain with an imprinted halfpenny stamp on the front, half the price of sending a letter. With the address going on the front and the message on the back they were a great success, with over 75 million sent in Britain in 1871, rising to over 800 million by 1910.

In 1894 picture cards were introduced but only really took off when, in 1902, the now familiar divided back postcard was introduced with room for both the address and the message on the back and an image on the front. One of the first companies to exploit this new market was Bamforth & Company Limited of Holmfirth, producing picture postcards from 1903, often using scenery sets from their photography work which had been their previous line of business.

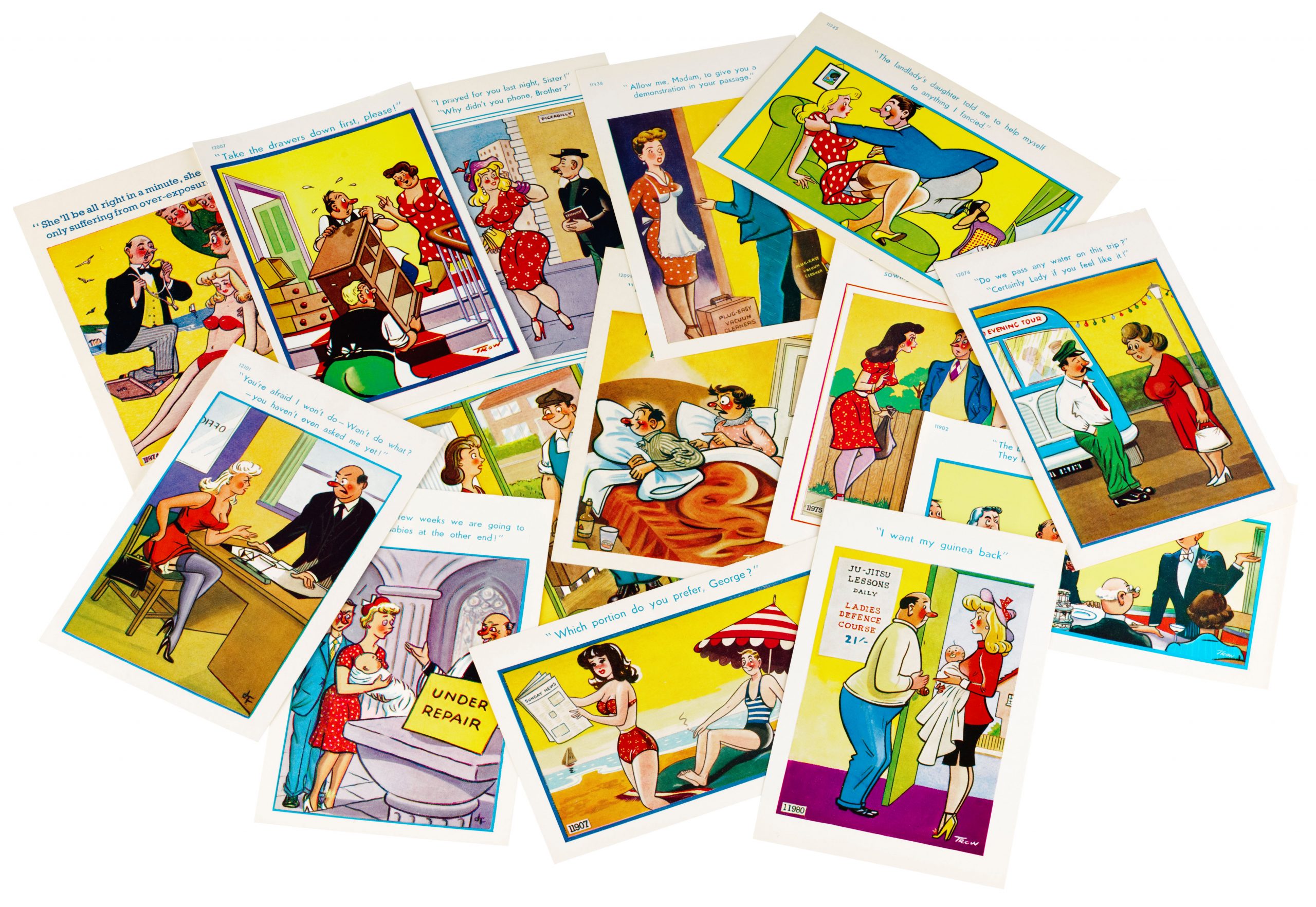

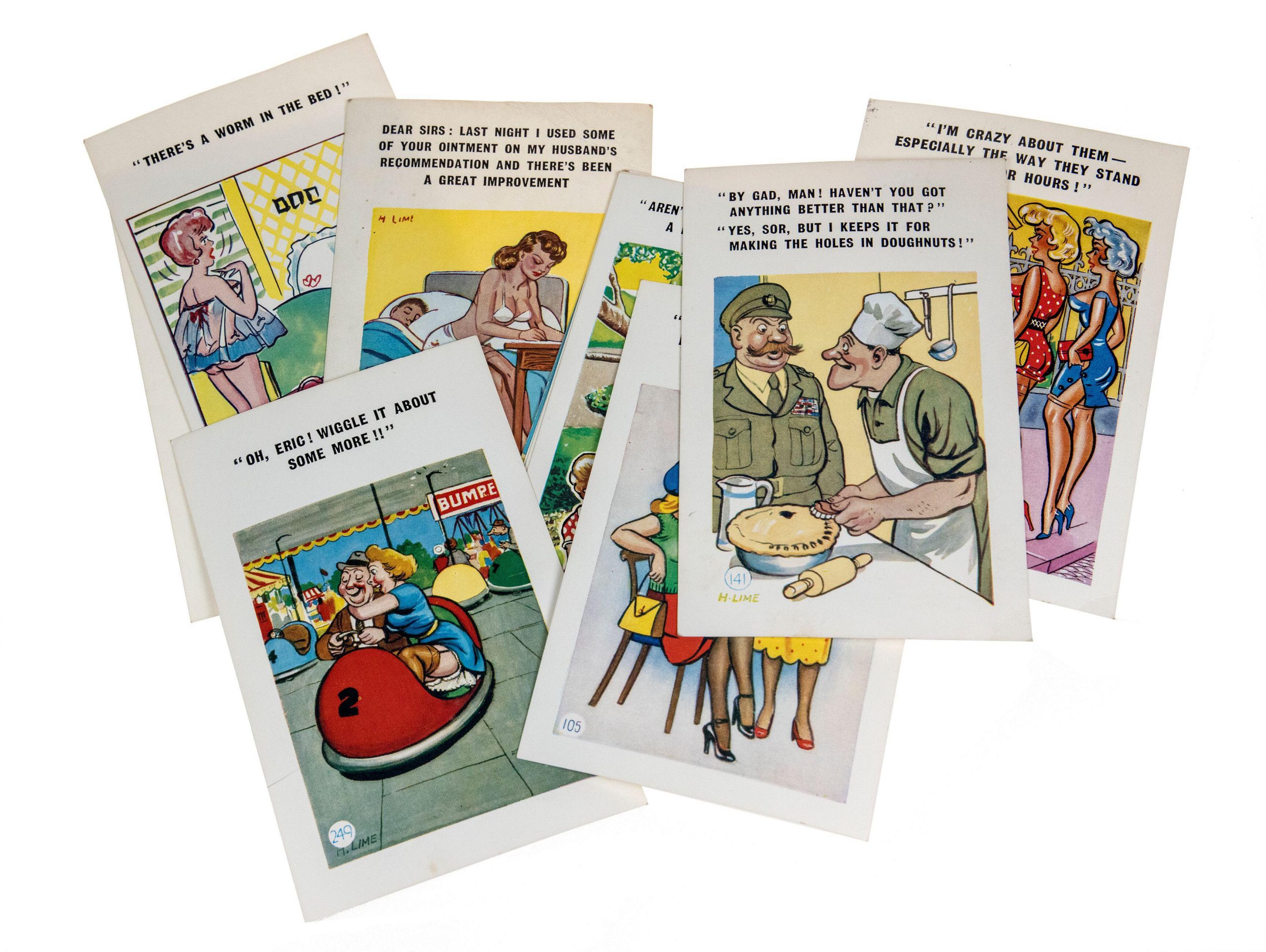

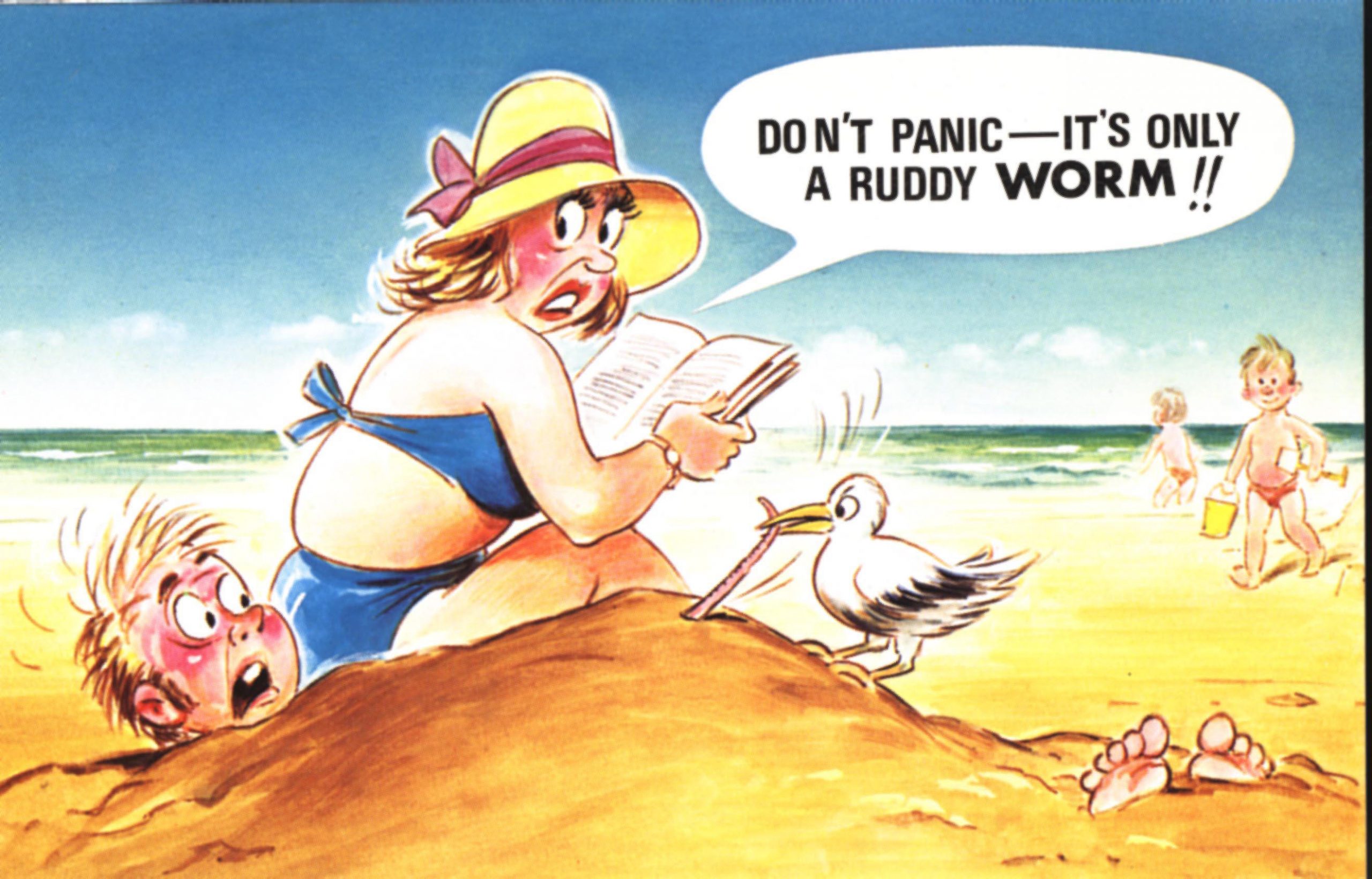

In 1910 they began to tap into an even more lucrative market, employing the skills of amongst others, Donald McGill, a former naval draughtsman, to produce comic postcards to sell to holidaymakers. Over a fifty year period McGill, the ‘King of the Saucy Postcard’, produced around 12,000 designs, for each of which he received no more than three guineas, What he called a ‘skit on pornography’ adorned over 200 million postcards and were instantly recognisable for their stylised images and risqué jokes.

Women were either young and shapely or middle-aged and fat, men were hen-pecked or strapping Adonises, professionals were stereotyped, lawyers as swindlers, vicars nervous and inept, and double-entendres and schoolboy humour ruled the roost. McGill’s most successful design featured a bookish man asking a pretty woman whether she liked Kipling, to which she replied ‘I don’t know, you naughty boy, I’ve never kippled!’, and sold over six million copies, a world record.

It was as if there was a complete transformation of the British psyche when they went on holiday. Those who would ordinarily reject any form of impropriety could not get enough of the postcards. Writing in 1941, George Orwell described them as ‘a genre of their own, specialising in a very ‘low’ humour, the mother-in-law, baby’s nappy, policeman’s boot type of joke, and distinguishable from all other kinds by having no artistic pretension’.

Although he appeared to be sniffy about them, Orwell was not advocating that they disappear. Instead he thought that they fulfilled a psychological need, appealing to the baseness which we all need from time to time to give expression to or as he put it, ‘on the whole, human beings want to be good, but not too good, and not quite all the time’. By the early 1950s Bamforth’s series of comic postcards was its best-selling line, leading Punch magazine to hail McGill as ‘the most popular, hence most eminent English painter of the century’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, not everyone shared Punch’s enthusiasm or Orwell’s understanding. There was to be a sea change in the attitude of public authorities which was to imperil the future of the saucy seaside postcard. Believing that public morals had declined during the Second World War and that the dial needed to be reset, the director of public prosecutions, Sir Theobald Mathew, together with the police, led the assault on postcard smut.

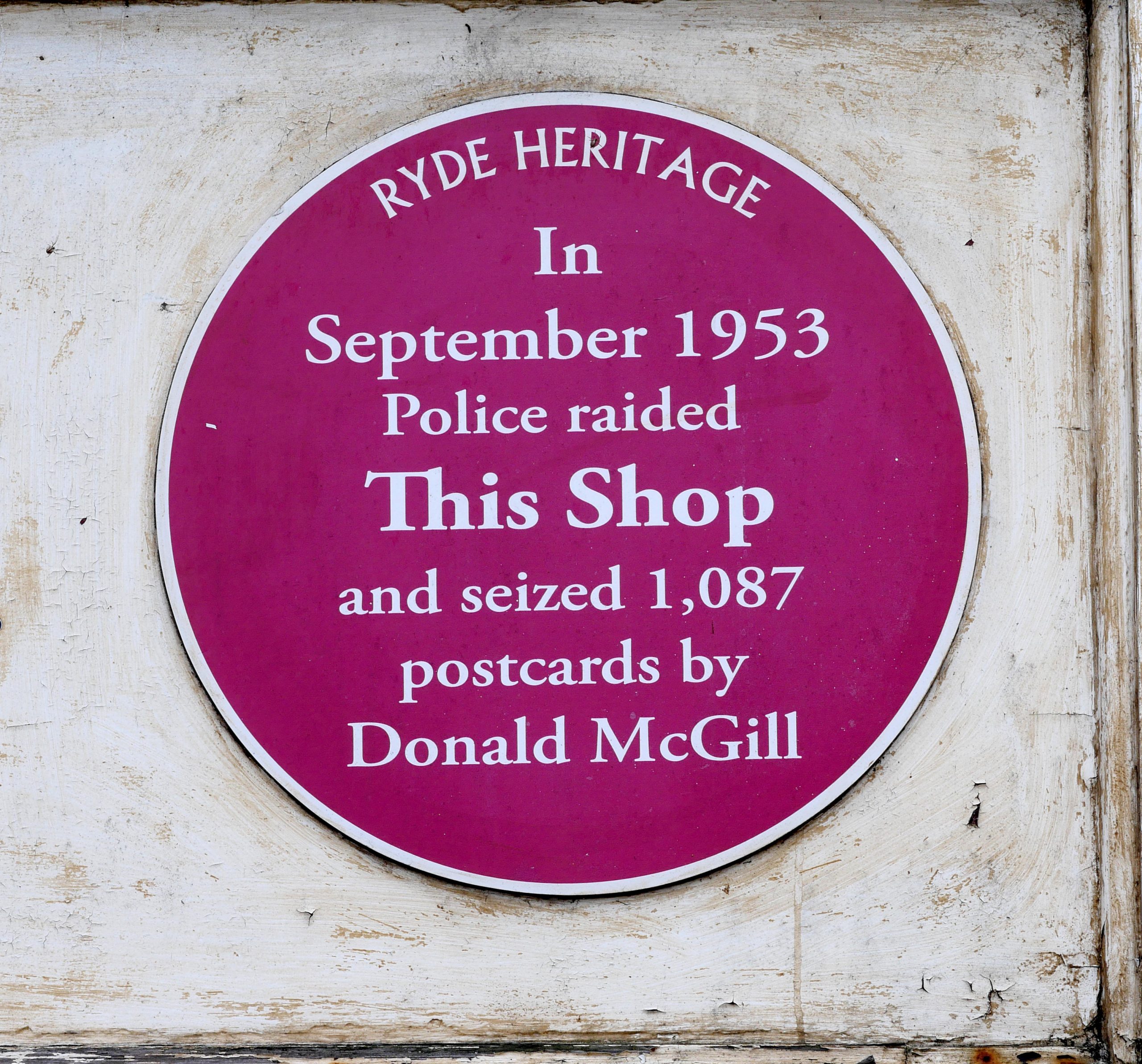

In Blackpool, acting upon information received, a plain clothes officer would visit a shop, pick up the offending postcard, ask the shopkeeper whether they would sell it to their daughter, invariably receiving the response ‘No’, and then a prosecution would follow. Once the word got out, other shopkeepers would withdraw their stock of those postcards from sale. In 1953 32,603 postcards were seized under the Obscene Publications Act (1857).

In most major seaside resorts Watch Committees, self-appointed and made up of local worthies, were set up to vet and deal with reports of ‘obscene’ cards in their area, ostensibly to reassure shopkeepers that if a certain design passed muster, they would be immune from prosecution. However, there was no national standard as to what was deemed to be offensive, although jokes about wind and other forms of toilet humour seemed high on the list, and so a postcard that was deemed to be acceptable in one resort could be banned in another. The general air of uncertainty led to the wholesale withdrawal of such postcards from sale.

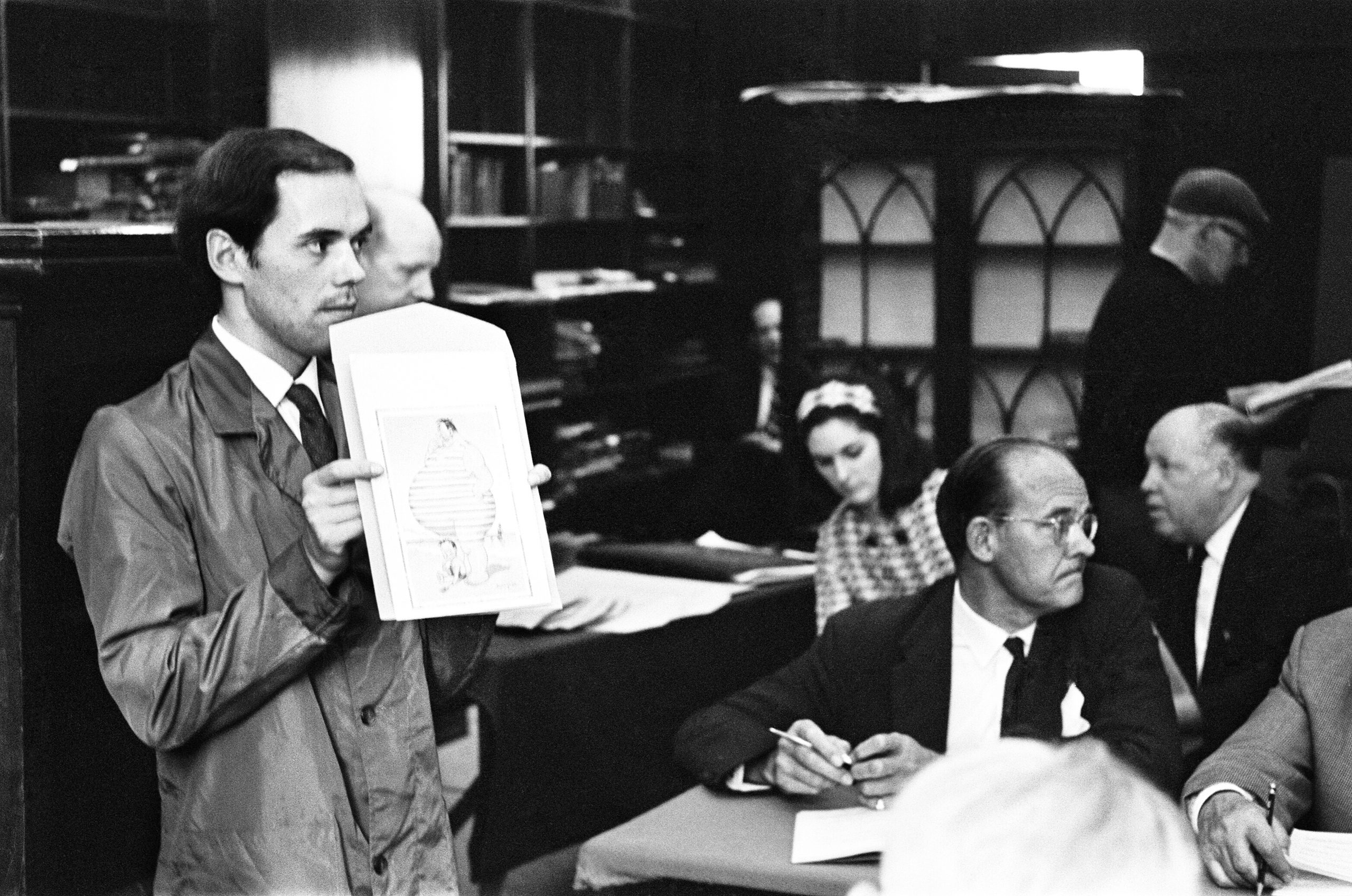

However, the moral crusaders were not done and had the ‘King of the Saucy Postcard’ and his publishers, Bamforth, firmly in their sights, finally bringing a charge of breaching the Act against him in July 1954. McGill’s lawyers posed the not unreasonable question: ‘are the cards capable of corrupting the minds and morals into the hands they come?’ Surprisingly, McGill based his personal defence on naivety, claiming that ‘in quite a number of the cards in question I had no intention of ‘double meaning’ and, in fact, a ‘double meaning’ was in some cases later pointed out to me’.

McGill was found guilty, fined £50 with £25 costs, with four of his offending postcards banned immediately and his publishers prevented from reissuing seventeen others. The verdict sent shock waves through the postcard industry, retailers cancelling orders and withdrawing stock and some smaller publishers even going into bankruptcy.

The tide, though, began to turn once more. In 1957 a House Select Committee, considering amending the Obscene Publication Act, invited McGill to give evidence. He argued that a national censorship system would not work due to the vagaries of individual taste. The subsequent changes to the law led to the loosening of censorship powers, culminating in Sir Theobald Mathew’s unsuccessful attempt in November 1960 to prosecute Penguin Books over the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and the waning of the tyranny of Watch Committees. The stage was set for the return of the saucy postcard.

McGill, though, hardly benefited from the renaissance, dying in 1962 having prepared all his designs for the 1963 season. He left an estate of just £735 and was buried in an unmarked grave in Streatham Park cemetery. And yet within just a few years his originals became collectable: in 1967, Sotheby's held a sale of his work, with US President Lyndon Johnson's daughter among those who attended. All this happened before even McGill's last few designs were published, which came in 1968.

The final nail in the coffin of saucy postcard industry was a change in public taste. From the modern perspective their subject matter was sexist, sometimes racist, certainly politically incorrect, occasionally xenophobic or homophobic, as outmoded as the humour of Benny Hill, the televisual manifestation of the saucy postcard. There was no place for them in the 21st century.

Despite that, McGill’s original colour-washed drawings sell for several thousand pounds a time at auction and pristine examples of his postcards are highly sought after.

His work was displayed at the Tate Britain exhibition, Rude Britannia: British Comic Art, in the summer of 2010, and there is a museum dedicated to him in Ryde on the Isle of Wight. That surely would have brought a wry smile to his face.

Find our more about Donald McGill and seaside postcards at the museum's website, saucyseasidepostcards.com

Credit: Getty Images

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel posters

The works of British poster king John Hassall remain a breath of fresh seaside air, says Lucinda Gosling.

Britain's Victorian seaside towns: A tale of sun, sand, affection, neglect, decay and regeneration

Country Life's cultural commentator Athena looks at the sad plight of Britain's seaside towns, but has hopes that things may

Britain's best seaside architecture: The playful details that shaped our coastal towns, from funicular railways to Victorian masterpieces

What is it that makes the buildings of the seaside so distinct? Kathryn Ferry looks at the vibrant architecture of

Credit: ©David Hurn / Magnum Photos

In Focus: The photographer obsessed with why we all like to be beside the seaside

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.