Why the British love eccentric collections – and what you need to know to start your own

The British are inveterate collectors of all sorts of items – Country Life's Anna Tyzack caught up with several of them.

Collecting as a hobby might date back to ancient Egypt, but it seems to have found a perfect marriage with the British penchant for eccentricity. There is something quite magnificently bonkers about scouring the land for knick-knacks that tickle your fancy – even if nobody else sees the appeal. Indeed, that dash of contrarianism probably makes a good find all the sweeter.

While you could spend thousands collecting things which you love, it need not be an expensive hobby – and if you follow these six simple rules (as provided by the collectors we spoke to below), you won't go far wrong.

- Follow your heart and your passion – don’t be led by fashion

- Work with dealers to make sure what you’re buying is genuine

- Go to museums and read books – you can never do enough research

- Attend sales and flea markets as well as searching in shops – part of the fun of collecting is the hunt

- Beware of eBay. It might seem an easy way to build a collection, but there’s no rebate

- If something seems too good to be true, it probably is

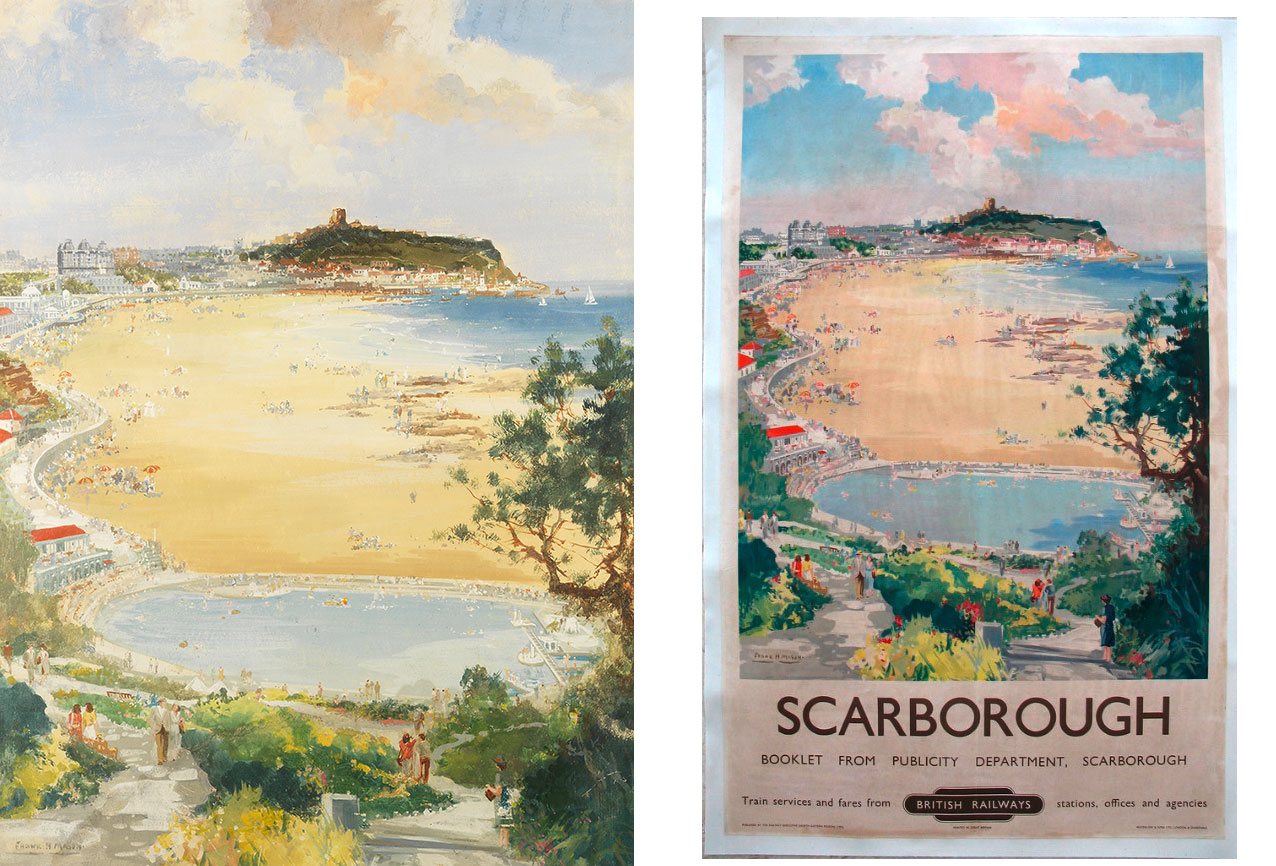

Jon Baddeley, original watercolours of 20th century railway posters

Antiques Road Show presenter Jon Baddeley – who is also a director of Bonhams in Knightsbridge – collects watercolour originals of early-20th-century railway posters.

And he believes that there is an inherent collector in all of us: ‘It begins with an object that gives you joy and leads to a life of fairs, markets, museums and libraries, plus endless cataloguing, displaying and storing.’

So why do we enjoy it so much? Mr Baddeley lists a number of reasons, including nostalgia, the pleasure of bringing order to chaos and the thrill of the chase.

It only takes a small budget to lay the foundations of a collection, according to Mr Baddeley. ‘You can start by buying chipped or blemished pieces and then invest in those in perfect condition when finances permit,’ he says. ‘It’s a hobby that can grow up with you.’

He advises fledgling collectors to ‘buy with your heart’, but to make sure their collection can be easily displayed in the home. ‘If you have to store it away in boxes, it takes all the fun out of it,’ he warns. It’s also a good idea not to focus on something too fashionable – collectables such as Rolex watches are plagued by fakes and replicas. ‘Remember – if something looks too good to be true, it probably is.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Mr Baddeley's watercolour originals are so unfashionable that the artworks often cost less to buy than the posters themselves. But is there marriage value in putting objects together in a collection? Don’t count on it, he cautions – your money is safer in the stock market. ‘However, if you invest in stocks and shares, you’ll only enjoy it when they go up. A collection gives joy all the time.’

David Lowe, grandfather clocks

Noon is a noisy time of day in David Lowe’s home near Salisbury, Wiltshire, owing to his collection of 11 grandfather (or longcase) clocks. ‘I try not to make phone calls approaching midday – it takes up to 10 minutes for them all to chime,’ explains the barrister, who also collects Staffordshire figures and has more than 230 paintings and engravings, including Britain’s largest collection of paintings by Margaret Neve – each one is separated on the walls by ‘just a 5cm gap’, but he and his wife ‘weren’t prepared to get rid of any of them’.

Each of his clocks has its own character: there’s a Scottish model from a ladies’ club in Edinburgh, with Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake painted above the face, an early, one-handed country clock and another with a chain that occasionally slips off its cogs, prompting an ear-splitting crash.

He bought his first longcase, by Will Snow of Otley, at an auction in Leeds, in 1955, when he was just 12 years old. ‘It’s numbered 619 and, once, years later, when I was seeing clients in their dining room about an inheritance dispute, they happened to have number 620,’ he recalls.

In 1957, he invested in another clock, by Anthony Hudson of Preston, and bought his third, by Thomas Beeching of Rye, in 1972 for £150. A grand provincial clock, it has a blue-lacquered moon-dial. ‘My wife and I collected it in our Renault 4 and had to strap the case on the roof,’ he recalls. He also has a rare Regency dial clock, purchased from an antique shop in Dorchester while waiting for one of his daughters to take her driving test: ‘I couldn’t resist it.’

It takes Mr Lowe more than half an hour to wind all the clocks, but he couldn’t bear to part with any of them due to their ‘fine faces and interesting cases’. The clocks have even influenced the type of house his family has lived in over the years. ‘We tried to downsize from our old rectory in 2004, but ended up in a larger, even more dilapidated old rectory,’ he confesses.

Sheridan Parsons, Teasmades and a doll’s house

Not long after Sheridan Parsons bought herself a vintage Teasmade machine in 1993, she came across one that she preferred and bought that one, too. Seventeen years later, she had amassed more than 170. ‘I got so caught up in them that I couldn’t let go,’ she admits. ‘The tea-making aspect never interested me – it was the designs and the stories behind the inventors.’

Now, however, she’s run out of storage space in her garage and is selling her collection on Ebay – the rarest, a 1932 Absolom, is listed for £500. ‘I’ve invested in a doll’s house instead,’ she reveals. ‘It’s the perfect collection for me as it’s completely containable.’

Miss Parsons bought two houses before settling on a 1964 suburban villa, which she’s furnishing with items made by A. E. Twiggs, the joiner and toy manufacturer.

He began making doll’s houses and miniature furniture in the 1940s for officers at RAF Fighter Command at Bentley Priory, Middlesex, when he was suffering from a nervous breakdown following service in the Air Raid Precautions in London. After the war, his wife, Rona, took examples of his furniture to Harrods, Selfridges and John Lewis, all of which agreed to stock it.

Miss Parsons’s doll’s house is a work in progress, but she’s already tracked down a grand piano, a kitchen set and a rose-pink bathroom suite. ‘It’s mass-produced, but in the way things were in the old days,’ she smiles. ‘And there’s a limited range. Once you’ve bought everything, that’s it.’

Laura Stoddart, Staffordshire dogs

Laura Stoddart is so passionate about collecting that she wrote her university dissertation on the subject. ‘I love researching, cataloguing and arranging rows of similar things,’ she enthuses. ‘It makes everything seem better.’ The illustrator hails from a family of devoted collectors: her mother’s blue-and-white straining plates adorned the walls of her childhood home in Cheshire, her brother, Sebastian, collects Cosy Craft insulated tea sets and rolling pins and a cousin has more than 100 glass candlesticks.

Miss Stoddart has several collections – model trees, lustreware jugs, jelly moulds – but her most treasured is an assortment of single Staffordshire flat- backs. ‘They usually come in pairs, but I only collect singletons that have lost their partner,’ she explains.

The dogs inspired her new illustrated stationery range, Odd Dogs: ‘I usually collect things I want to draw as it’s easier to illustrate objects that are already stylised.’ Another range is based on her mother’s collection of pink lustreware teacups.

Miss Stoddart advises new collectors to set themselves a £10 spending limit to ‘heighten the thrill and the challenge’. ‘Although not as easy as it used to be, it’s still amazing what you can find at flea markets and in charity shops,’ she concludes.

Mark Hannam, Roman coins

When Mark Hannam was nine, he uncovered an old penny on a grass bank on West Cliff, Bournemouth, using a metal detector bought for him by his father. ‘I’ll never forget how exciting it was – it inspired not just a hobby, but my career,’ admits Mr Hannam, who is a collectables expert for Fieldings Auctioneers in Stourbridge in the West Midlands, where his annual coin sales have generated more than £1 million over the past decade.

During hunts across Britain, from Bournemouth to Bridgenorth, he’s amassed a private collection of more than 60 hammered-silver coins, including a silver denarius bearing the bust of Emperor Otho (Marcus Salvius Otho Caesar Augustus), who was Roman emperor for three months in ad69, the Year of the Four Emperors.

‘I get an enormous adrenaline rush when I find a new piece,’ says Hannam, who has been collecting Roman coins for most of his life. ‘It’s often when I’ve already walked several miles, but, afterwards, I can keep going for the rest of the day.’

Some of his pieces might sell for a few hundred pounds, but he can’t bring himself to part with any of his finds: ‘Each one tells a story. My favourite piece of all, a bronze eagle, has been the subject of lectures I’ve given to local historical societies and groups.’

Mr Hannam gives a word of warning to aspiring collectors: ‘Be sure to get permission before searching on anyone’s land – it’s also important to record discoveries with the local finds liaison officer. It’s not just about digging it out of the ground and putting it in your pocket.’

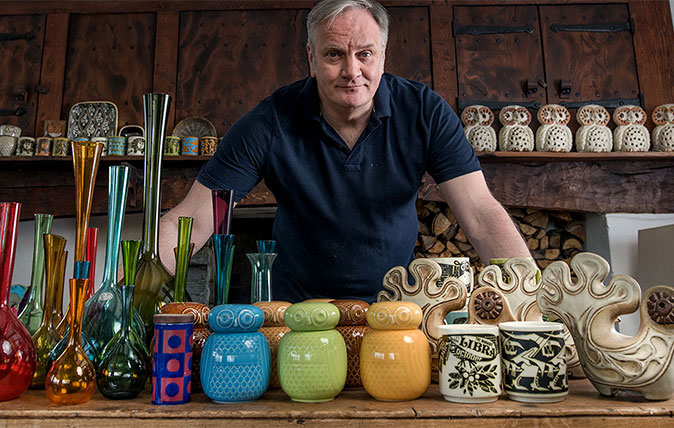

Peter Francis, Gullaskruf glass and Hornsea ceramics

A large blue vase by the Swedish glassmaker Gullaskruf (1893–1995) first caught Peter Francis’s eye in a gallery in London 15 years ago, but it was only when he moved to an Arts-and-Crafts house in the Lake District, designed by Baillie Scott, that he began collecting glassware.

‘I studied one of the long, deep window sills and realised that what it needed was Gullaskruf glass vases,’ recalls Mr Francis, who was production designer for the ‘Harry Potter’ film series and Titanic. ‘They’re not expensive, but they’re examples of good design, which fits with the ethos of the house,’ he elaborates.

Originally, Mr Francis only looked for green vases by the same designer, Arthur Percy, but, in time, he permitted red and blue into the collection. ‘The house is eccentric and doesn’t lend itself to colour themes,’ he explains. ‘However, the oak surfaces are perfect for displays.’

He also collects mid-20th-century Hornsea ceramics, having grown up near Hornsea, and has a number of mugs and owls. ‘As a production designer, I’m always putting things together to create environments for a story and I suppose my home is my story: a bit muddled, but in an orderly way.’

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Curators, art historians and other creative minds share their pick of J. M. W Turner's best works, on the 250th anniversary of his birth

Curators, art historians and other creative minds share their pick of J. M. W Turner's best works, on the 250th anniversary of his birthCold moonlight, golden sunset and shimmering waters are only three reasons to love Turner. On the 250th anniversary of his birth, curators, art historians and other creative minds reveal which of his paintings they’d hang on their walls and why.

By Carla Passino

-

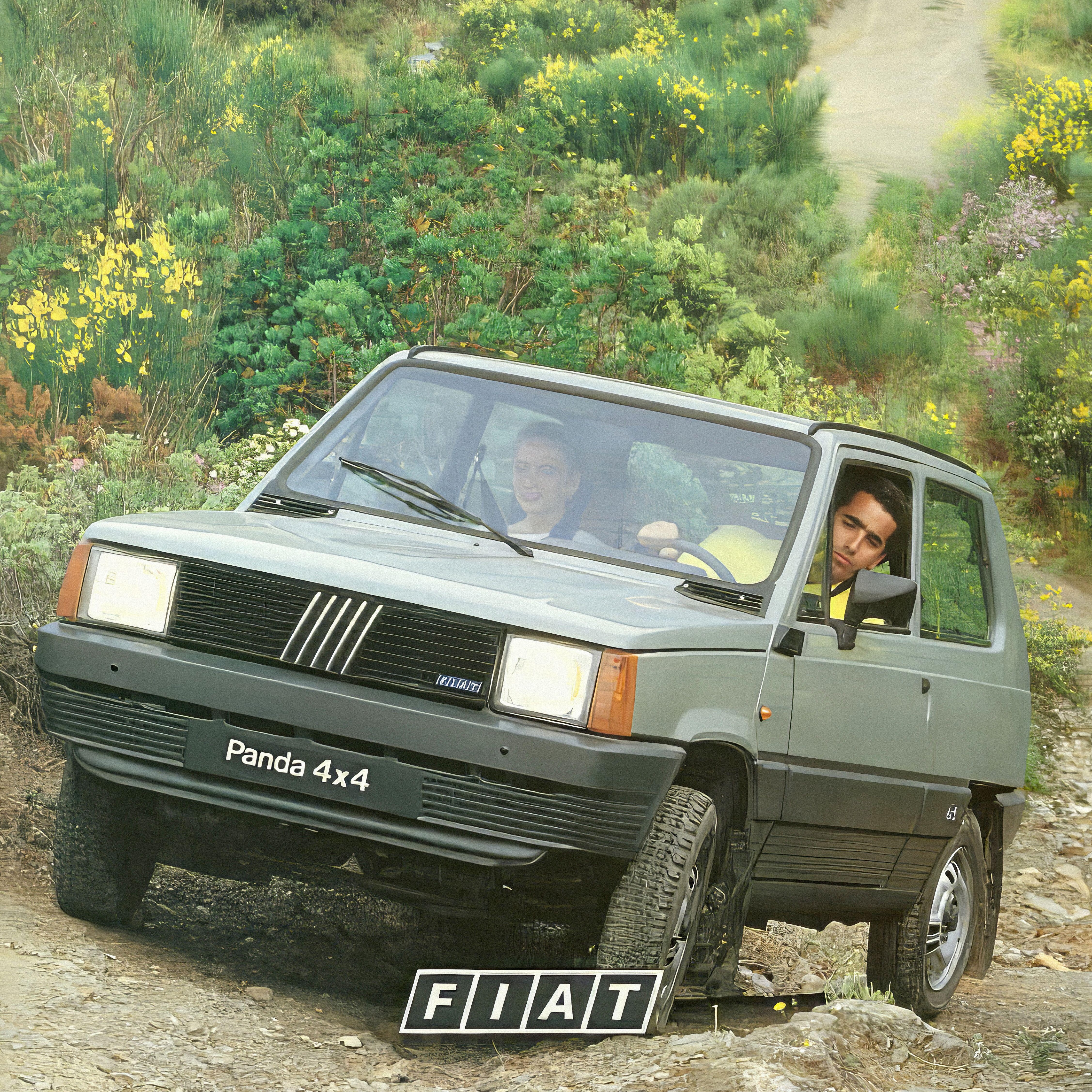

Boxy but foxy: How the humble Fiat Panda became motoring's least-likely design classic

Boxy but foxy: How the humble Fiat Panda became motoring's least-likely design classicGianni Agnelli's Fiat Panda 4x4 Trekking is currently for sale with RM Sotheby's.

By Simon Mills

-

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’s

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’sThere are only 200,000 Birkin bags in circulation which has helped push prices of second-hand ones up.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

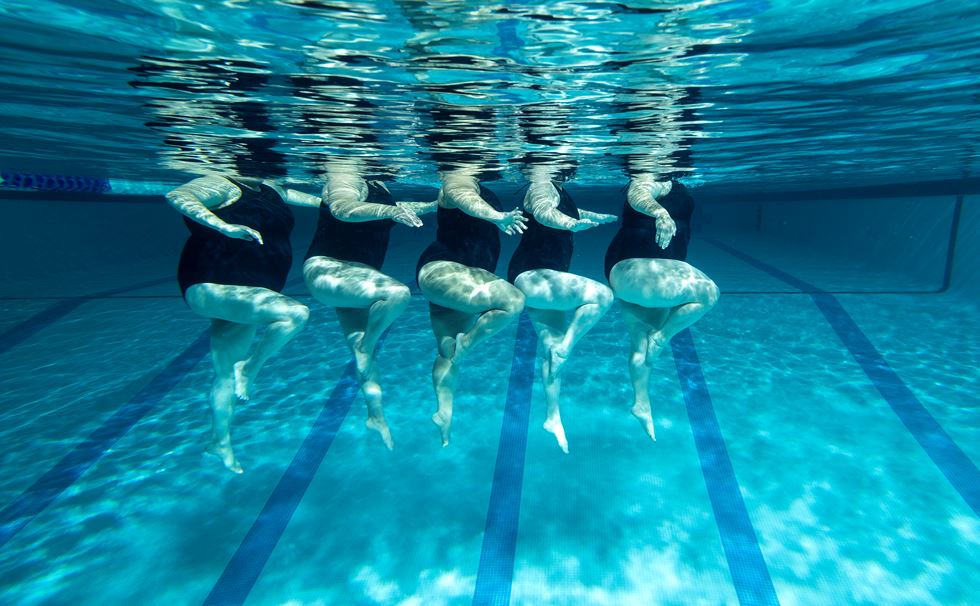

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes

-

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasuresEvery diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

By Jonathan Self

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino