The Arts and Crafts House at Compton Verney

Clive Aslet reflects on the themes of the Arts and Crafts house.

Compton Verney, the 18th-century Warwick-shire mansion set in a Capability Brown park, isn’t, at first sight, the most obvious place to show an exhibition of the Art-and-Crafts home. Robert Adam, who worked there in the 1760s, represented everything that the movement didn’t like, but the location explains the choice of theme: only a few miles away are the Cotswolds, a sleepy, agricultural area in the 19th century, which, after the arrival of William Morris at Kelmscott Manor in 1871, became Arts-and-Crafts central.

It was the restoration of St John the Baptist church in Burford that inspired Morris to found the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, one of the stones upon which the conservation movement was built. The reinvention of Compton Verney, from ruin into art gallery, fully opened in 2004, chimes with the Morris ideal.

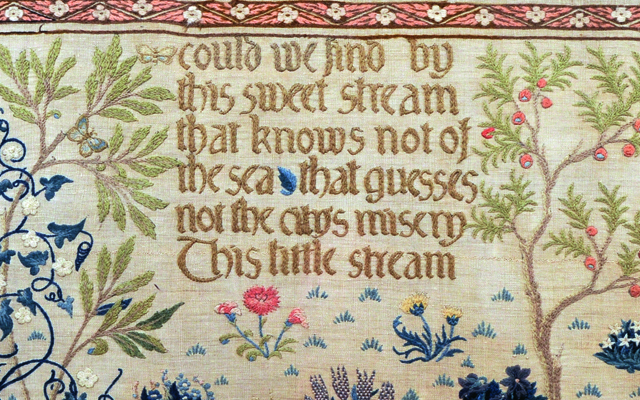

Home was intensely important to Arts-and-Crafts architects. The nation had taken a wrong turn at the Industrial Revolution and it was through the family and large household that society would be put right. Making things, communal life and Nature were the loadstones. ‘If I Can’ is the motto, embroidered repeatedly in wool, along with some rather wooden-looking birds, on William Morris’s first textile, made by his own hand in 1857.

Before long, Morris had founded a company dedicated to the production of hand-woven textiles and hand-printed wallpapers that would introduce colour and pattern, chivalry and Nature into what might otherwise have been drab Victorian interiors.

Strangely, Morris himself didn’t favour them in the main rooms at Kelmscott; his personal taste was for white walls and the occasional piece of wooden furniture. This remained the aesthetic of followers such as Ernest Gimson and the Barnsley brothers, characterised by a very upright and cushionless Gimson settle. The Arts-and-Crafts practitioner was too busy doing to be comfortable.

The exception is M. H. Baillie Scott, who designed seductively pretty rooms, often for middle-class budgets, but the suggestion of commercial success was enough for some people to disparage him as Arts-and-Crafts lite. His work is too sunny to be serious, for this purpose; the spiritual leaders of the movement lived with a sense of doom, as society continued to rush headlong in the contrary direction to the one that they prescribed as the path of health and happiness.

I learnt from the exhibition that the great engraver F. L. Griggs was, by temperament, a gloomy, perhaps depressive man characteristics that help explain the black shadows and brooding quality of his images.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A sense of battle having been unequally joined with an unfeeling world is suggested in the dedication of his engraving of Owlpen Manor: ‘To my friend NORMAN JEWSON, who, with one only purpose, & at his own cost & loss, possessed himself of the demesne of OWLPEN when, for the first time in seven hundred years, it passed into alien hands, & with great care & skill saved the ancient house from ruin.’

Not everything was saved from ruin by the Arts-and-Crafts movement and many of its ventures ended in failure and shattered dreams another reason for the importance of home, as a refuge from the cruelties of the world.

Which makes this show’s emphasis on modern equivalents to the tradition refreshing. Beside an Alfred Powell punchbowl of 1928, painted with a Cotswold scene, is an urn-shaped tureen by Michael Eden, its open filigree sides giving the impression of having been twisted while still wet. As well as C.

F. A. Voysey’s adorable design for a nursery chintz, on the theme of The House that Jack Built, the show offers Rosa Nguyen’s equally playful Gardening with Morris, in which a wall of Morris wallpaper, overpainted so that only some random organic shapes are visible, has been hung with glass seed-like shapes holding examples of the plants associated with the oeuvre.

Although C. R. Ashbee’s attempt to establish a craft colony at Chipping Campden in 1902 was among the Arts-and-Crafts movement’s heroic flops, it left a legacy in the silversmithing workshop of George Hart; this continues in the hands of his grandson David, great-grandson William and great-grandnephew Julian, as well as Derek Elliott, who served his apprenticeship with David. Their work is the subject of a concurrent exhibition at Compton Verney.

And, imaginatively, Compton Verney has been working with the gardener Dan Pearson, whose thoughts have been focused on the Arts-and-Crafts movement from his work at Lutyens’s Folly Farm, where the Jekyll garden has been reinterpreted in a modern idiom (as can be seen from photographs in the exhibition). Mr Pearson has transformed the West Lawn at Compton Verney into a wildflower meadow.

The inspiration is William Morris’s Trellis wallpaper, the bars of the trellis being represented by mown paths. As the different seeds contend with each other, the meadow will change in character every year, until, in seven years’ time or so, it reaches a point of equilibrium. This not only reflects the role that Nature played as a key inspiration of the Arts-and-Crafts movement, but leaves open the possibility of other artists using the meadow as a canvas for their own creative ideas in other seasons. Bravo!

‘The Arts and Crafts House: Then and Now’ and ‘The Hart Silversmiths: A Living Tradition’ are at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, until September 13 (01926 645500; www.comptonverney.org.uk)

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver