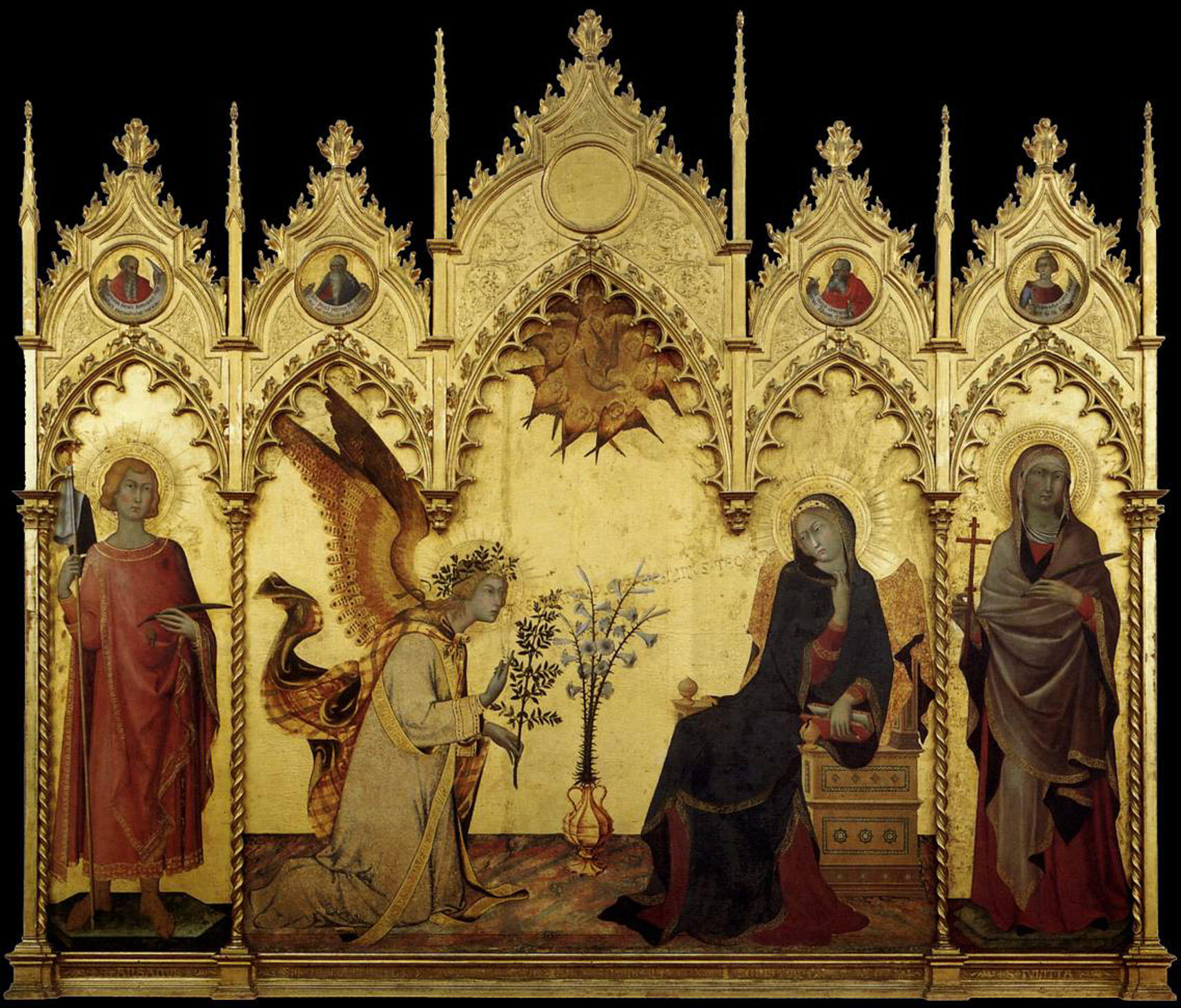

A new National Gallery exhibition shines a light on Siena’s brief, but dazzling golden age

In the space of 100 years, Siena's artists redefined painting as an art form and laid the foundations for Renaissance.

In his celebrated Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government (1338–39), Ambrogio Lorenzetti depicts an idealised Siena as the model of civic and social order. Against a panoramic backdrop of castellated buildings and vine-terraced hills, shopkeepers and packhorse tradesmen ply their wares as peasants till the fields and hunting nobles ride out into the Tuscan campagna through open, but well-fortified, city gates.

Ground-breaking for their secular theme, Ambrogio’s frescos in the Palazzo Pubblico’s Sala dei Nove loomed over meetings of the elected officials of the Guelph oligarchy that ruled Siena. Peace with arch-rival Florence had ushered in a period of stability and the beautiful brick-built city was clamorous again with pageantry and its legendary horse races. Plans were under way for a vast extension to the cathedral, the showcase for superb works of sculpture and painting, and construction had begun on the townhall’s dizzying campanile, the bells of which, it was said, could be heard in Rome. Merchants, craftsmen and money changers established themselves along the principal thoroughfares, trading furs and leatherwork, lapis lazuli, ‘Saracen’ carpets and ‘Tartar cloths’. Goldsmiths created composite artworks of breathtaking ingenuity and financiers established the world’s first bank.

This was Siena’s golden age and it saw the flowering of a local school of art led by Duccio di Buoninsegna and his followers, Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers. Whereas his Florentine contemporary, Giotto, was revolutionising painting with his earthbound spatial and emotional realism, barely a day’s ride away, Duccio was creating otherworldly images of lustrous beauty, using chiaroscuro and tender gestures to humanise the Madonna and Child against burnished gold, symbol of divine light. The touching composition of his Stoclet Madonna (1290–1300), in which Christ twitches playfully at his mother’s veil, echoes that of a Parisian ivory carving of a few decades earlier, reminding us that here, on the main pilgrimage route to Rome, such portable works of art played a significant role in transmitting the style and iconography of the northern Gothic masters.

The growing prestige of Sienese artists was reflected by the prominence given to their work in civic, as well as religious, commissions in a city dedicated to the Virgin. In the magnificent seat of the Republic, an enthroned Madonna presides over the council chamber, offering through painted inscriptions her protection over Siena as her child advocates justice. Signed and dated 1315, it is Simone’s earliest documented work, an astonishing feat considering he was in his twenties when it was commissioned. Seated under a heraldic canopy on a cushioned Gothic throne, the Virgin is a dreamy, courtly figure wearing a crown and veil over braided locks and a flowing, geometrically patterned gown. Gilded, tooled and once glittering with fragments of coloured glass, the fresco conveys the material splendour of medieval nobility, yet it projects a solemn message: Simone’s Madonna in majesty is Siena’s divine patron and also queen of the Republic, a terrestrial version of the Maestà that Duccio had painted for the cathedral’s high altar four years earlier. Comprising more than 50 panels of tempera-painted poplar wood integrated into a pinnacled frame, Duccio’s double-sided altarpiece was the largest and most complex ever produced, its procession to Piazza del Duomo on June 9, 1311, accompanied by jubilant crowds and musicians.

It’s difficult to believe that this pivotal masterpiece of the 14th century could have succumbed to changing fortunes and antiquarian taste; however, in 1771, it was dismembered and 33 of its parts were sold off. Some are now lost, some in international collections. Sawn apart, the main front and reverse faces — the Maestà and 26 scenes of the Passion — were eventually moved to the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, where they can be viewed alongside other surviving pieces. Even in this dismantled state, it’s possible to appreciate Duccio’s astounding achievement and see how it shaped the work of his successors.

Architecture frames the narrative of 'The Birth of the Virgin' by Pietro Lorenzetti, whom Vasari deemed to have surpassed Giotto

Siena’s tradition of high-quality devotional panel painting made it a leading producer of altarpieces — multi-panelled, almost sculptural objects that integrated the work of painters, craftsmen and architectural framers. From the workshop he ran with his relations, Simone became the unrivalled master of the medium, commissioned by a network of royal, aristocratic and religious patrons from Naples to Avignon. Inspired by Siena’s superlative goldsmiths, he developed such techniques as sgraffito to imitate luxurious figured silks, creating effects not achievable in fresco.

After Simone departed for Avignon in the mid 1330s, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti emerged from his shadow to dominate Siena’s artistic scene. Pietro had worked itinerantly in Umbria and Tuscany, forging connections and absorbing influences, notably that of Giotto, whose fresco cycle in Assisi he completed, prompting Vasari to observe that he surpassed the Florentine master in technique. His altarpiece for Arezzo’s Santa Maria della Pieve (about 1320) synthesises the influences of Giotto and Duccio in an exquisitely designed polyptych that makes sophisticated use of architecture to frame the gold-backed figures. In their different styles, the brothers developed Duccio’s narrative innovations. Pietro’s The Birth of the Virgin and Ambrogio’s episodes from the life of St Nicholas use architectural settings to stage chronological events happening simultaneously. Human emotion is nowhere more charged than in the dramatically composed Crucifixion of Ambrogio’s late career.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The 'Wilton Diptych' is a supreme example of Simone’s far-reaching elegant and technically refined style

The fluid movements of artists and patrons stimulated the taste for Sienese painting and decorative arts among a web of interconnected patrons in cities and courts across Europe. During his final decade in cosmopolitan Avignon, then the Papal seat, Simone’s elegant, technically refined style became widely emulated, influencing courtly art as far afield as Bohemia and Britain. The National Gallery’s Wilton Diptych (1396–99) is a supreme example, combining the influences of French Gothic sculpture with the finest Sienese techniques of sgraffito and modelling in egg tempera.

By the time the Diptych was painted, Siena’s population (including the Lorenzettis) had been decimated. Even the Virgin could not save her city from the plague of 1348. Although its influence would continue into the 15th century, the Sienese school never regained its ascendency. Its art would come to be coveted again during the medieval revival, when painters and collectors were drawn to the ‘sweet spirituality’ of the ‘Italian Primitives’. Britain led the field and, by 1887, the National Gallery had a room dedicated to Sienese art. Its forthcoming exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300–1350, reunites some of these precious masterpieces with their original companions, notably the gallery’s three panels from Duccio’s Maestà. Two of these have been reassembled with the five other surviving scenes from the rear predella, offering a rare chance to see some of Duccio’s most daring narrative episodes in their original sequence. It’s an opportunity that should not be missed.

‘Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300–1350 is at the National Gallery, London, until June 22.

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.

-

A day walking up and down the UK's most expensive street

A day walking up and down the UK's most expensive streetWinnington Road in Hampstead has an average house price of £11.9 million. But what's it really like?

By Lotte Brundle

-

Life in miniature: the enduring charm of the model village

Life in miniature: the enduring charm of the model villageWhat is it about these small slices of arcadia that keep us so fascinated?

By Kirsten Tambling

-

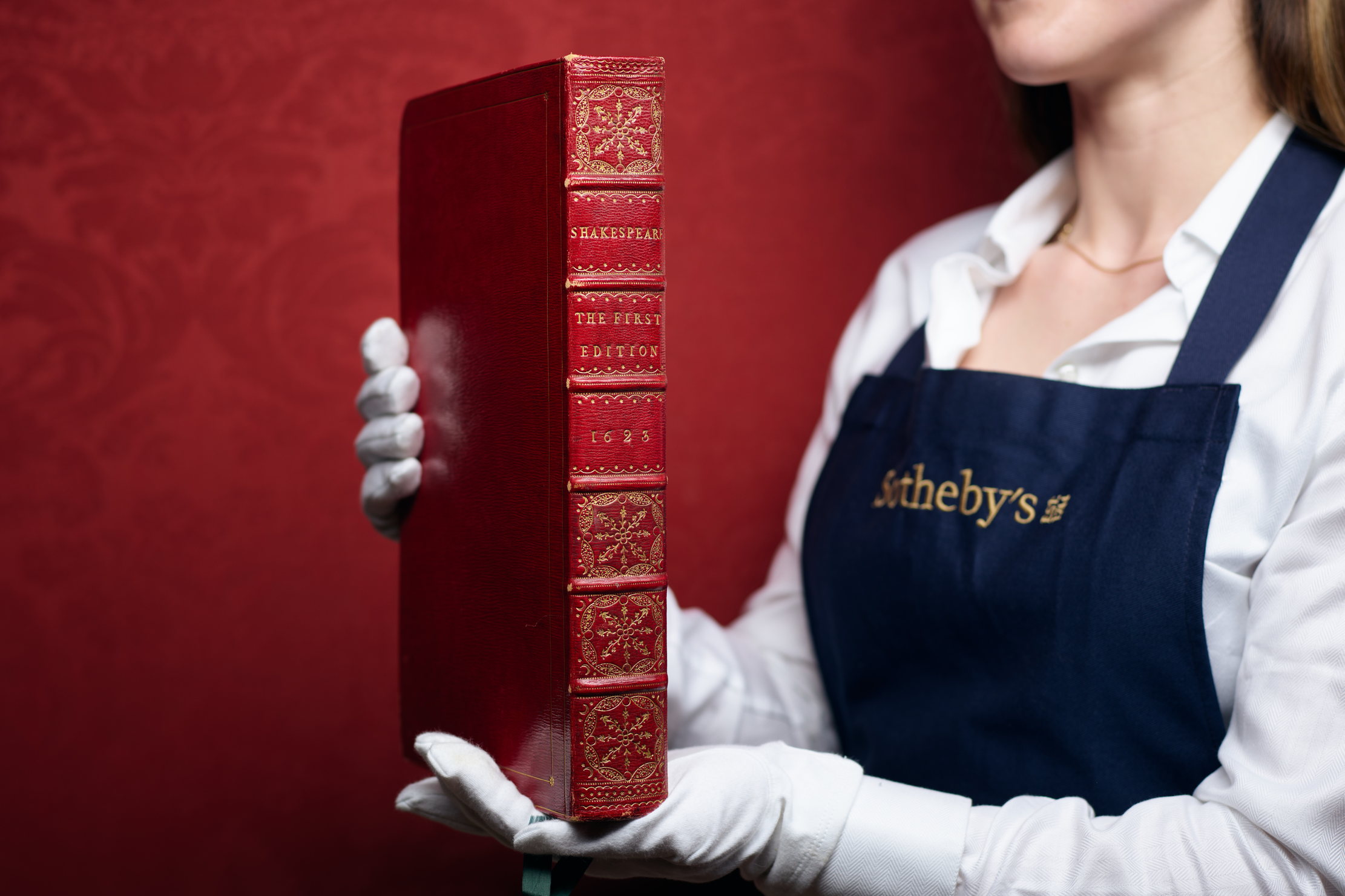

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Curators, art historians and other creative minds share their pick of J. M. W Turner's best works, on the 250th anniversary of his birth

Curators, art historians and other creative minds share their pick of J. M. W Turner's best works, on the 250th anniversary of his birthCold moonlight, golden sunset and shimmering waters are only three reasons to love Turner. On the 250th anniversary of his birth, curators, art historians and other creative minds reveal which of his paintings they’d hang on their walls and why.

By Carla Passino

-

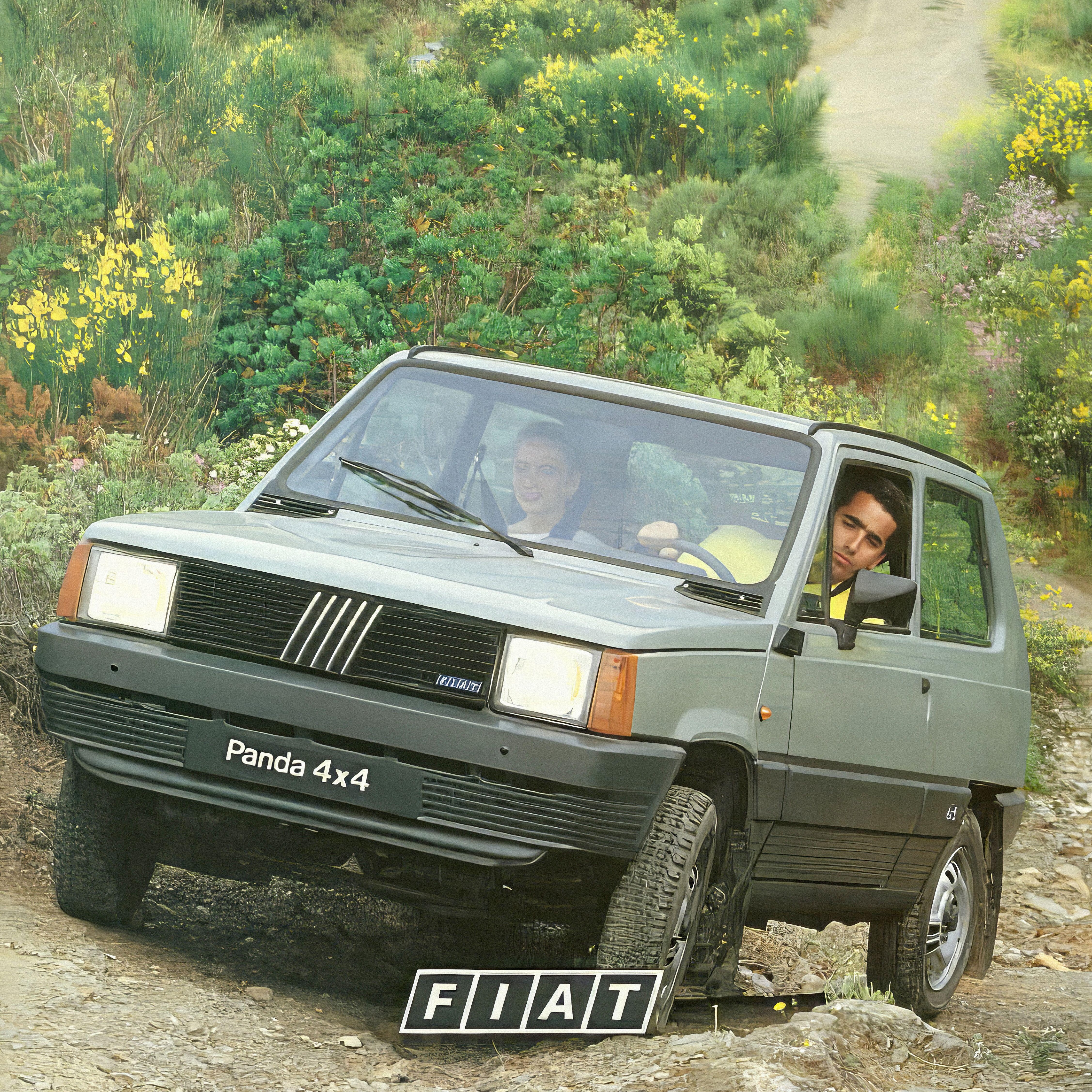

Boxy but foxy: How the humble Fiat Panda became motoring's least-likely design classic

Boxy but foxy: How the humble Fiat Panda became motoring's least-likely design classicGianni Agnelli's Fiat Panda 4x4 Trekking is currently for sale with RM Sotheby's.

By Simon Mills

-

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’s

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’sThere are only 200,000 Birkin bags in circulation which has helped push prices of second-hand ones up.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

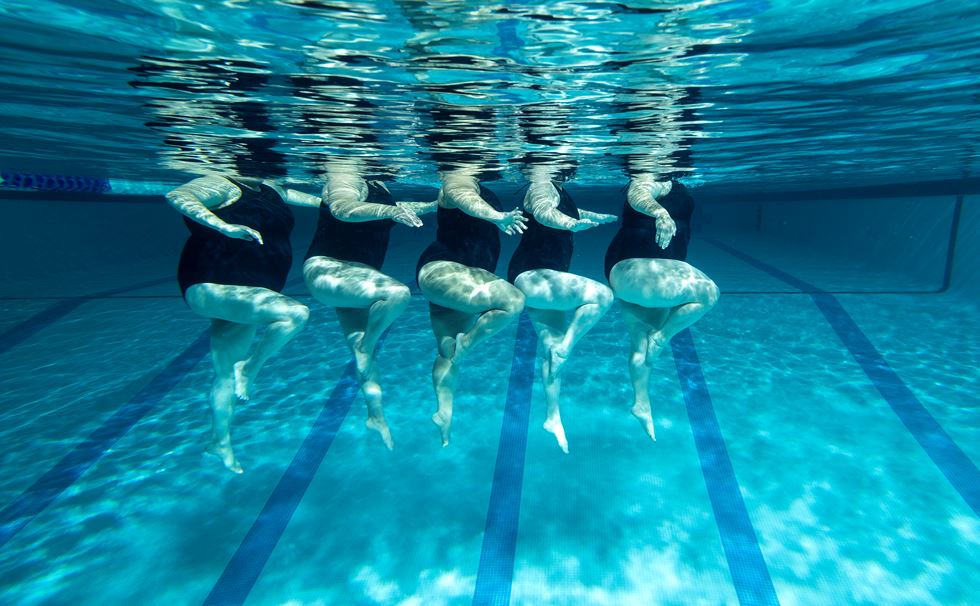

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes

-

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasuresEvery diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

By Jonathan Self

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu