The genius inventors who created the world's most important clocks

Early clocks had variable hours, but even in the golden age of British horology, when Thomas Tompion made his masterpieces, a man relying on public timepieces could end his walk earlier than he had started. Huon Mallalieu traces the evolution of British clock-making.

Archbishop Ussher calculated that the world began at 6pm precisely on October 22, 4004BC. More recent scientists tell us with relatively less certainty that the Big Bang occurred 13.799 billion years ago. In both calculations, the existence of time is unquestioned, the unstoppable flight of its arrow analogous to the doxology’s glory of God, ‘which was, is and ever shall be’. It is currently fashionable among some physicists to regard time as an illusion, with the ‘now’ as the only reality (more simply expressed in the Earl of Rochester’s Love and Life: ‘The present moment’s all my lot,/And that as fast as it is got, Phyllis, is only thine’). However, once we accept the necessity of time, whenever its starting point, then it becomes necessary to measure it.

The earliest measuring devices were water clocks, shadow clocks and sundials and the earliest hours were variable, depending upon daylight, latitude and season — indeed, variable-hour clocks were used until the 19th century in Japan, where it would have been reasonable to enquire: ‘How long is an hour today?’ Elsewhere, the noon-to-noon passage of the sun gave us the 24 fixed-hour system, as measured by both Chinese and Alfred the Great’s candle clocks.

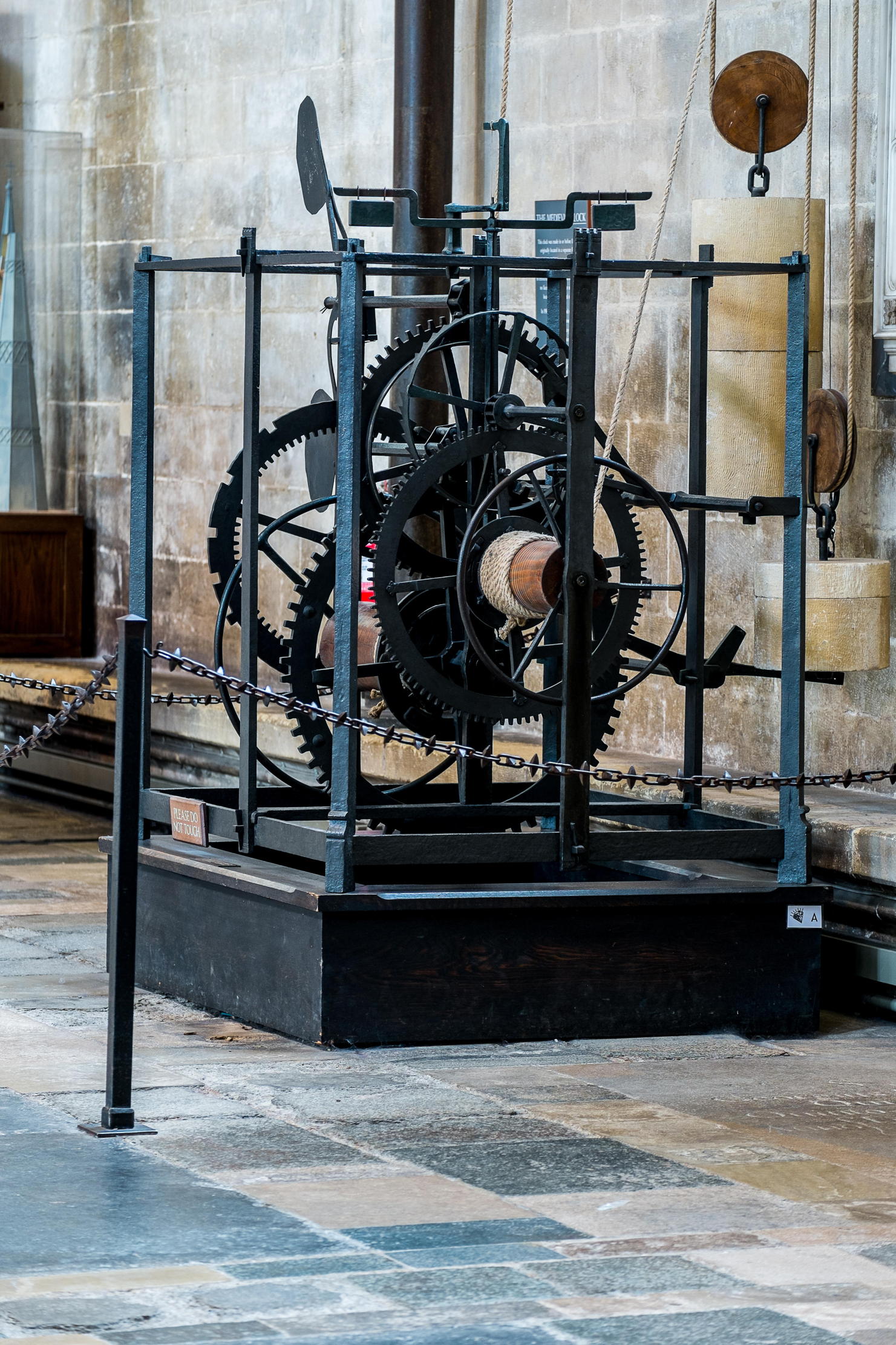

The first mechanical clocks, from the 13th century, were powered by stone (later brass) weights and used a verge escapement driving a foliot wheel to strike bells on the hour. Probably the oldest working survivor is the Salisbury Clock (about 1386), whereas the near-contemporary Wells astronomical clock, the movement of which is in the Science Museum, was one of the earliest to have a dial.

From the early 15th century, weights began to be replaced by mainsprings, adapted from coiled springs in locks, gradually allowing for smaller, portable clocks and, indeed, watches. Inventions tend to have many fathers, although usually only one has naming rights, and that is true of the development that dominated horology for three centuries.

Galileo and the Jesuit astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli were working on the application of pendulums to timekeeping earlier, but it was Christiaan Huygens (1629–95) who invented a weight-driven pendulum clock on Christmas Day, 1656, as he recorded, and it was patented the following year.

The pendulum both encouraged the development of longcase clocks and made smaller table clocks practical. These are known as bracket clocks, although it was no longer essential for them to be supported on walls to allow for weights. The pendulum, together with the slightly later balance spring for watches, increased accuracy from a loss or gain of up to half an hour a day, to no more than a couple of minutes.

The 1657 patent was taken out on behalf of Huygens by Salomon Coster (1620–59), the maker, and Huygens-Coster clocks were exported to Florence, Paris and London within the year. Huygens was also the inventor of an endless rope drive, allowing much longer running durations.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Among Coster’s workforce at that time was John Fromanteel, one of many links between Dutch and British clockmakers. The exact connections between individuals and the passage of influence between them are matters of continued dispute between horologists of the two countries. An earlier link was Cornelis Drebbel (1572–1633), who had been summoned to the English capital by James I to provide machinery for Court masques, together with the architect Inigo Jones and playwright Ben Jonson. As an engineer, Drebbel also built the first operational submarine (the King was a passenger) and he may have passed his knowledge of optics, lenses in particular, to Huygens’s father, Constantijn, a statesman and patron who visited London on various diplomatic missions. In between periods in England, Drebbel also worked for the Emperors Rudolf II and Ferdinand II in Prague with the Swiss clockmaker Jost Bürgi.

The Fromanteels were Protestant immigrants from Flanders and John’s father Ahasuerus has been credited by some as the maker of the first pendulum clock in England. Certainly, as wooden cases came into fashion, together with pendulums, he was one of the foremost makers of cases for the new bracket or table clocks and, in particular, he developed the characteristic use of very thin ebony veneers. The strong, classically architectural forms of English clock-cases in the 1660s and early 1670s may be due to the connection not only to Jones, but also to Jones’s assistant and successor John Webb. From the 1670s to the 1720s, table clocks tended to be less rigidly architectural and the tops generally had variations of basket or cushion domes with carrying handles. At the same time, longcase clocks were decorated with olivewood or walnut veneers, rather than burr walnut, ebony or ebonised pearwood, and their hoods retained classical or spiral-twisted columns.

Ahasuerus Fromanteel was associated with the Cromwellian regime and, although he was willing to compromise his Puritan preferences and work in classical and Baroque styles after the Restoration, he retired to the Netherlands for a while, before returning to take advantage of the 1676 Great Fire of Southwark and set up business in an area that was free of City restrictions and had a tradition of furniture-making.

As architectural purists sometimes regard 1660–1720 as the pinnacle of British country-house building, so are those decades described as the classic age of English clock-making, when skill, innovation, function and beauty were most closely aligned. It is not possible to refrain from quoting Sacheverell Sitwell’s judgement that: ‘Thomas Tompion seems to be marked as head of his profession by the mere music of his name, as its syllables chime slowly and solemnly on the ear.’

Tompion (1639–1713) was the head of his profession indeed, but many others stood near him in eminence, most notably the Fromanteel dynasty, Edward East (1602–about 1695), Joseph Knibb (1640–1711), Daniel Quare (1647/8–1724) and Tompion’s nephew-by-marriage George Graham (1673–1751). As the 18th century progressed, good, but not necessarily innovative, clockmakers established themselves in all major centres.

Tompion was the son of a Bedfordshire blacksmith and it seems likely that he had contact with East and Knibb and began as a journeyman for Fromanteel. An early patron, probably introduced through Knibb, was the scientist Robert Hooke, with whom he had a testy relationship. Major royal backers included — as well as the later Stuart monarchs — Queen Anne’s underestimated husband, Prince George of Denmark, whose significance has recently been uncovered by the horologist Richard Garnier. Not only was Tompion renowned for his skills as a designer and maker, but so, too, were his workmen, many of them Huguenots, such as Daniel and Nicholas Delander. When he had established his style, Tompion began to produce clocks in batches, meaning that it was necessary to number the various parts so that they could be assembled correctly: by the end of his career, he had numbered 580 clocks, as well as about 4,000 watches. The numbering was continued by Graham, his successor in the business.

Those were clocks for the rich. In 1693, a Tompion for William III cost £600, perhaps the equivalent of about £104,000 today, and, a couple years earlier, another royal commission was said to have cost £1,500, more than £300,000 now. The generality relied on public clocks, which varied widely in time-keeping. In 1693, a writer to the Athenian Mercury described his walk from London’s Covent Garden to the Royal Exchange, leaving as the clock struck two. He passed seven public clocks, all telling different times, and reached his goal apparently at 1.45. ‘This I aver for a Truth, and desire to know how long I was walking?’

After the 1720s, the movements of British clocks and, eventually, time became standardised and cases and dials followed fashion, with black and coloured japanning coming after marquetry, although for a while clocks lagged behind other furniture. Mahogany only ousted walnut in the 1750s, mantel clocks superseded table clocks and, from the 1830s, cheaper European and American longcases ended British manufacture. The swing of the pendulum continued, but no longer defined clockmaking

Britain's specialist antique clock dealers

Tobias Birch Evesham, Worcestershire, open by appointment only (01242 242178 or 07970 795892; www.tobiasbirch.com)

Carter Marsh No 32A, The Square, Winchester, Hampshire (01960 844443; https://cartermarsh.com)

Richard Price Bullpits House, Bourton, Dorset (01747 840084 or 07860 200209; www.antiqueclocks.tv)

Howard Walwyn 123, Kensington Church Street, London W8 (020–7938 1100; www.walwynantiqueclocks.com)

Ben Wright Crew House, Market Place, Tetbury, Gloucestershire (07814 757742; www.benwrightclocks.co.uk)

Curious Questions: Why do clocks go clockwise?

There's nothing to stop the hands of a clock from running backwards — indeed, some actually do — but the overwhelming majority

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.