150 years of the Impressionists, being celebrated in Paris and London

In 1874, a group of painters rejected by the official Paris Salon staged its own show and changed the course of art. It was France’s convulsed lurch into the modern era that helped spark the Impressionist revolution.

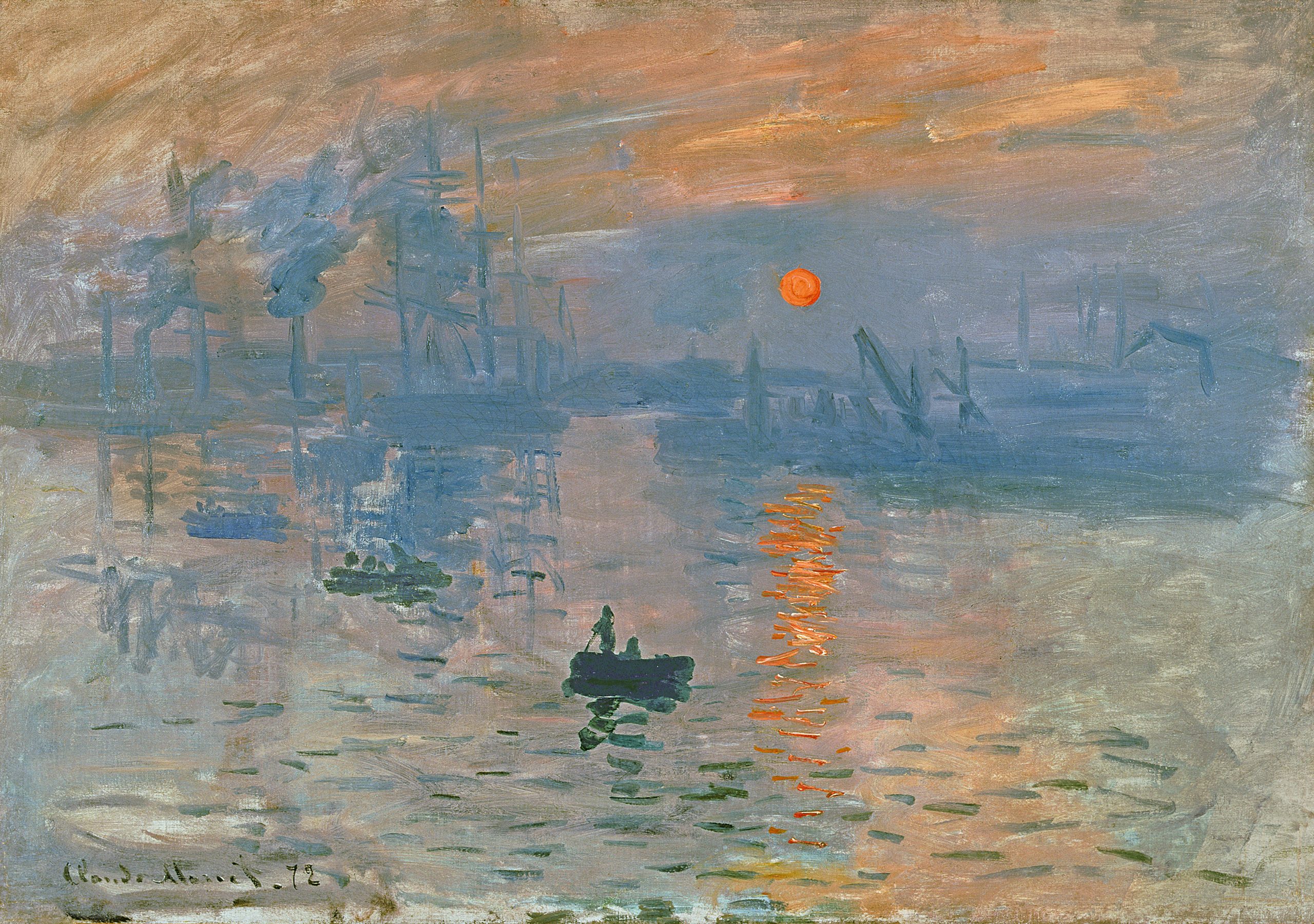

On April 15, 1874, a blazing orange sun rising over the port of Le Havre freed a fishing boat from the dull vestiges of the dying night and French art from the staid shackles of the Salon’s lifeless academia. Claude Monet’s Impression: Soleil Levant lent its name to the new, revolutionary approach to painting that was presented on that April day: Impressionism.

Exactly how different this style — full of loose brushstrokes and preoccupied with light — was from the rigid artistic traditions of the past emerges clearly from the Musée d’Orsay’s newly opened ‘Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism’ exhibition in the French capital, which presents a selection of the works exhibited in April 1874 next to paintings from the Salon of that time.

Nonetheless, the Anonymous society of painters, sculptors, and printmakers, as the group of 31 artists behind the first Impressionist exhibition called themselves, hadn’t initially set out to stage an artistic rebellion: ‘They wanted to exhibit, couldn’t exhibit in the official Salon and, therefore, found a way to create their own platform; but the fact that they did it was revolutionary,’ believes art dealer David Stern of Stern Pissarro. He is married to the great-grand-daughter of Camille Pissarro, artist Lélia Pissarro and, therefore, has both professional and familial ties with the movement, whose inaugural show he will commemorate with an exhibition, ‘Celebrating 150 years of Impressionism’, featuring works by Pissarro, Sisley, Degas and Renoir.

However, the art of the group was as much a product of the times as of the painters’ pioneering vision and individual talent. France, explains Allison Deutsch of Birkbeck University’s School of Historical Studies, had experienced frequent upheaval since the Revolution of 1789, including in 1830, 1832, 1848 and 1871. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and the radical experiment of the Commune of Paris that ended in bloodshed in May 1871 would have forced the young artists to join the military or seek refuge in the countryside: ‘The impact of war or dislocation cannot be overestimated. But revolutionary events were not foreign to them before 1870–71 either, because the memory of the revolution of 1848 permeated public consciousness and affected the art of their predecessors.’

Although France lurched violently into the modern era, the same years also saw rapid economic expansion, particularly during Napoleon III’s Second Empire (1852–1870). ‘Especially relevant to the evolution of Impressionism was the rise of the bourgeoisie,’ points out Dr Deutsch. ‘The expanding middle class was eager to see itself and its surroundings represented in art and in smaller canvases, which could be hung in their newly acquired domestic spaces. Impressionism fit the bill for some of the more open-minded members of this class.’

This was also an era of industrial and technological progress, with one advancement in particular playing a crucial part in the development of Impressionist art, according to Mr Stern: ‘Suddenly, tubes of paint were invented and you could go and paint out in Nature.’ Although John Constable in Britain and the Barbizon School in France had painted en plein air in the 1830s, the handy, portable tubes patented by American portraitist John G. Rand in 1841 and popularised in France later in the century made the task much easier. ‘As landscape impressionism came to be understood as seeking to capture the ephemeral moment in Nature, the quality of atmosphere and light at a specific time, being able to paint on the spot, in the field, became crucial both to how Impressionism was practised and understood,’ points out Dr Deutsch.

Progress also offered a new choice of subjects: ‘Impressionists,’ notes Dr Deutsch, ‘were some of the first to paint modernity as they saw it.’ As an example, Mr Stern cites Pissarro’s 1872 Bords de l’Oise, Environs de Pontoise: ‘You’ve got the chimney stacks on the right in parallel with the masts of the barge on the left and the smoke. That was modernism coming.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Perhaps more surprisingly, Impressionism was even influenced by French foreign and international trade policy. In the mid 19th century, when Japan was coerced to open up to the world after about two centuries of isolation, France pursued close diplomatic and economic ties. Among the most notable imports from the Asian country were ukiyo-e woodprints from late-18th- and 19th-century masters such as Hokusai, Eisen, Kuniyoshi and Kunisada: ‘Japanese prints were known for flattening out perspective, simplifying figures and objects, using unusual viewpoints and juxtaposing broad areas of flat, bright colour,’ observes Dr Deutsch. ‘Impressionism was understood in similar terms.’

Political, social and economic changes also affected the public’s reaction to the new art movement: the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the events of the Commune triggered a widespread crisis of confidence in French power, according to Dr Deutsch. ‘Art was called upon to be a source of pride and patriotism. So when [the Impressionists] organised their show in 1874, the stakes were high. Their art would be judged not simply as a reflection of a new aesthetic, but as a reflection of national identity, French culture and the state of the nation. For those who liked Impressionism, it represented the energy and initiative of young French artists. For those who hated it, it signified the degeneration of French culture.’

With politics swirling around their work, Impressionists were often labelled as revolutionaries. ‘It was as if their practice and exhibition strategies, which represented such a rupture from routine and tradition, aligned them with the political far left,’ remarks Dr Deutsch. In truth, only Pissarro had strong leftist views, with a long-standing interest in anarchy: ‘He subscribed to anarchist newspapers,’ explains Mr Stern. ‘The anarchists then were interested in less government intervention, less control: let the countryside people live their lives — he idealised that.’ The rest of the group, by contrast, was not particularly politically radical.

Yet, these accidental rebels did revolutionise art far beyond the confines of their country and their era. Although their movement was as fleeting as it was influential — from 1878, each of the Impressionists began looking at other ways of working, according to Mr Stern — they paved the way for Abstractism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism and, from there, much of contemporary art. Never did so few achieve so much in such a short time.

‘Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism’ is at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, France, until July 14 — www.musee-orsay.fr

‘Celebrating 150 years of Impressionism’ is at Stern Pissarro, London SW1, May 30–June 29 — www.pissarro.art

[collections]

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.

-

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?The King's recent visit to Nansledan with the Prime Minister gives us a clue as to Labour's plans, but what are the benefits of traditional architecture? And can they solve a housing crisis?

By Lucy Denton

-

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breeds

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breedsPhotographer Melody Fisher has been travelling the UK taking photographs of ‘vulnerable’ spaniel breeds.

By Annunciata Elwes