Not just for Christmas: The enduring appeal of jigsaws

Born as a brain-teaser to teach children geography, the humble jigsaw puzzle is now one of the world’s favourite pastimes. Ben Lerwill explores its enduring appeal.

You know the routine. It starts with a jumble of shapes, a chaos of coloured, irregular fragments poured across a floor or tabletop. Then begins the process itself: the sorting of the pieces, the patience, the pondering, the narrowly averted coffee spillages, the perseverance. It ends (assuming the dog, baby or vacuum cleaner doesn’t pilfer any vital components) with something true and tangible, a smooth, squared-off tableau to be admired with something approaching awe. Heaven.

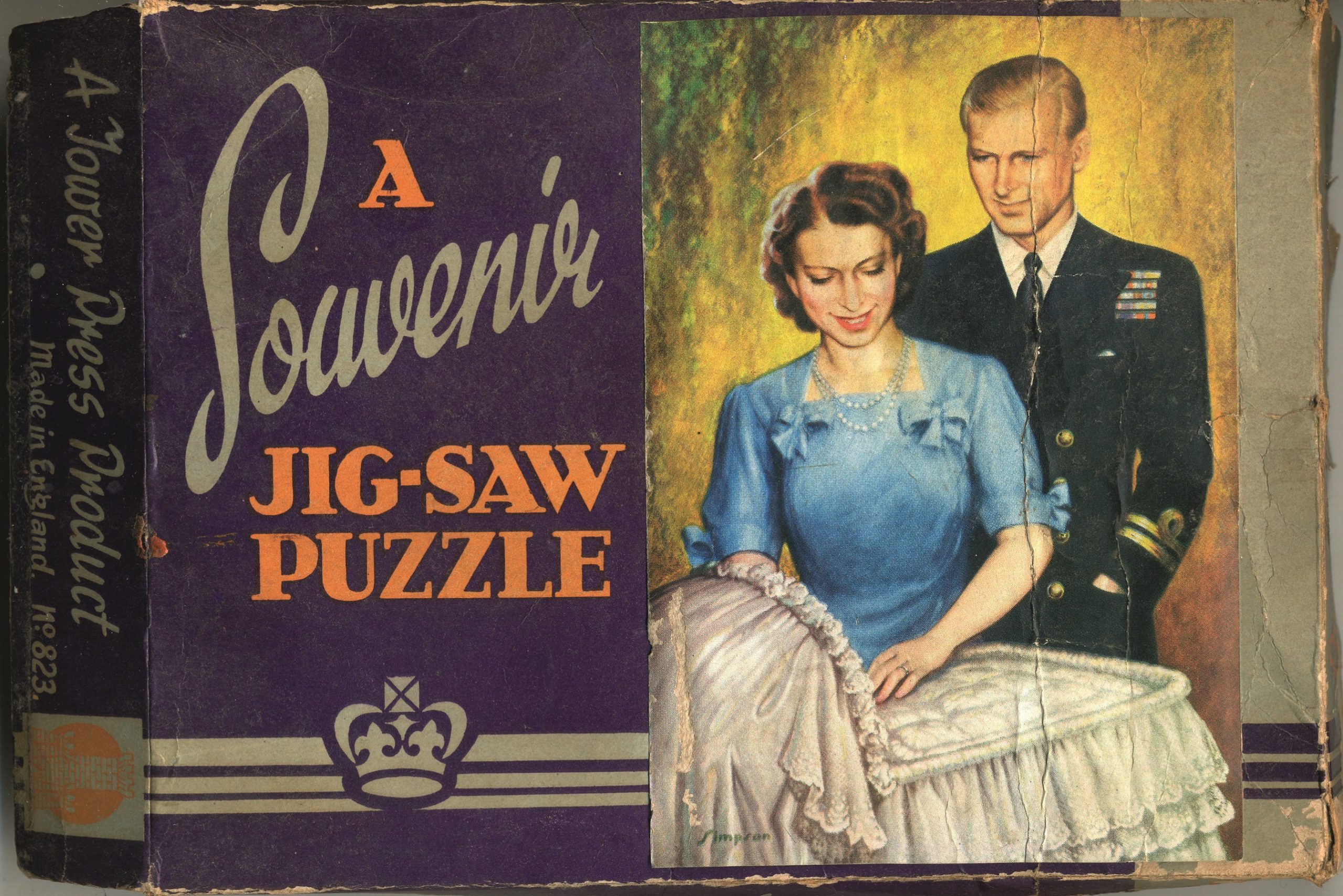

The humble jigsaw puzzle occupies its own niche in our pantheon of leisure pursuits. Elizabeth II was known to be an avid fan, seemingly taking great satisfaction from settling down to create order from disarray, and the pastime has now grown to the point where UK manufacturers sold an estimated £33.3 million worth of puzzles in 2021 alone. ‘They provide that opportunity to just sit and be,’ says Kate Gibson, managing director of Gibsons Games, a company founded by her great-grandfather in 1919 and now famed for its traditional, blue-boxed puzzles. ‘Your brain starts to work in a way that it can’t when you’re in the middle of your to-do list.’

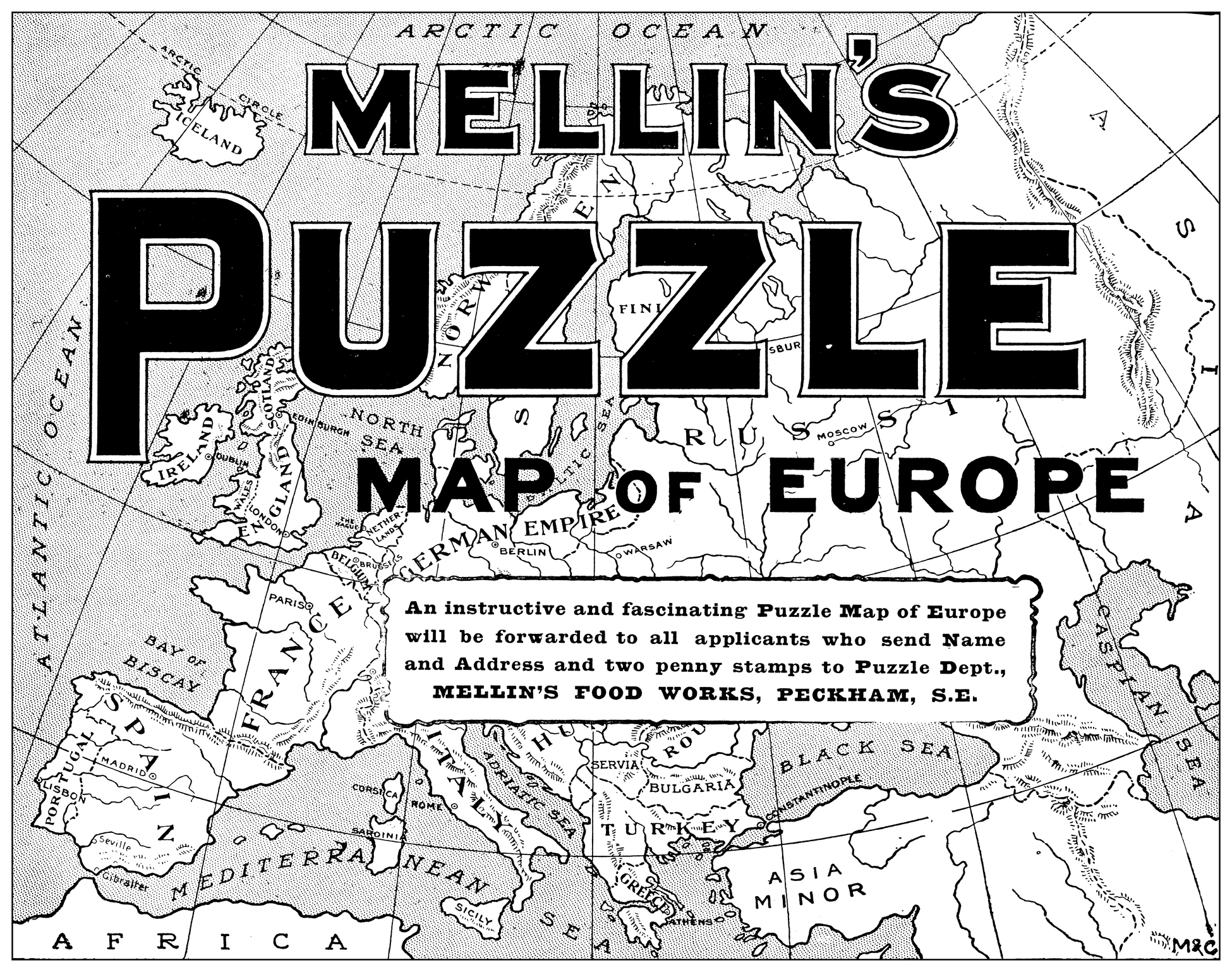

Despite their firm hold on our spare time, jigsaw puzzles have a relatively recent history. They began, as with many great inventions, almost by chance. In 1762, John Spilsbury, a London map engraver, was looking for ways to make geography more appealing to schoolchildren. He struck on the idea of creating a simple cartographic brainteaser by mounting a map of Europe onto a wooden board, then cutting around the country borders, creating pieces to be fitted back in by hand. The resulting product was a hit.

The rest — to leap from one classroom subject to another — is history. These dissected puzzles, as they were originally known, became popular educational tools, with other designers copying and commercialising the idea. Their subject matter began widening to include farm scenes, wildlife images and religious paintings, an early sign of the vast breadth of different designs they would later cover. As the years wore on, their appeal broadened beyond children to people of all ages.

It wasn’t until the latter stages of the 19th century, however, that the pastime could reach a far wider audience. Advanced printing techniques, coupled with the invention of plywood and the treadle jigsaw — the intricate shaping tool that would go on to give its name to the puzzle — ushered in a new era. Later, the introduction of easily manufactured cardboard pieces boosted this popularity even further.

‘Everyone who does jigsaws, whether they’re really hard puzzles or easier ones, will tell you the same thing,’ says Sarah Watson, managing director of Wentworth Puzzles, which still produces wooden jigsaws and counts the National Trust and English Heritage among its themed collections. ‘It’s a relaxing experience. It puts you in the moment.’

The lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 famously saw a boom in jigsaw purchases — what better way to fill a house-bound week? — and it’s fascinating to note that a similar sales increase was recorded during the Great Depression of the 1930s, as people looked for an affordable means of escapism from the woes of the world.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Recent times have seen another shift, not wholly tied to the pandemic. ‘Fifteen years ago, most of our customers were either retired or approaching retirement,’ continues Mrs Watson. ‘But, over the past decade, as mindfulness has become much more of a buzzword and people are spending more time looking after their mental health, we’ve definitely noticed far more customers in their twenties, thirties and forties.’

Not many pastimes can claim to be truly open to all ages and skill levels — Wentworth, for example, offers puzzles that range in size from 25 to 1,500 pieces — and perhaps even fewer can claim such an enduring appeal. Yet today, another great joy of a jigsaw puzzle is that it provides an antidote to digital devices. ‘A puzzle provides something away from our screens,’ observes Ms Gibson. ‘You can enjoy touching the pieces and putting them together. The tactile nature of the pieces is important.’

The popularity of jigsaws is by no means a domestic phenomenon — North America, Australia and Europe all have devotees in huge numbers — but there’s often a distinctly British flavour to the images on the puzzles themselves. Nature and rural life both tend to figure heavily, as do busy beach and city scenes — generally with a humorous tone — and puzzles with a Christmas theme also have a long habit of selling well. Many designs are created specifically for use in jigsaws. ‘There are definitely key ingredients,’ explains Ms Gibson. ‘Lots of sky obviously makes a puzzle difficult, so we try to fill space. Then we’re asking questions such as, does it evoke a feeling of nostalgia? Is it beautiful? Does it make you laugh? We look for designs that create an emotion.’ By giving someone a jigsaw, you’re offering them one of life’s simple pleasures. Be warned, however: the recipient might be occupied for some time.

Puzzling it out: jigsaw facts and figures

- Before the 1930s, puzzles were produced without boxed images for customers to follow

- Time on your hands? Ravensburger Memorable Disney Moments jigsaw has 40,320 pieces. You’ll need plenty of space to finish it, however — it measures 22ft by 6ft

- Bill Gates, Emma Watson, Kate Hudson and Hugh Jackman have all proclaimed their love of jigsaw puzzles. Mr Gates reportedly never holidays without one

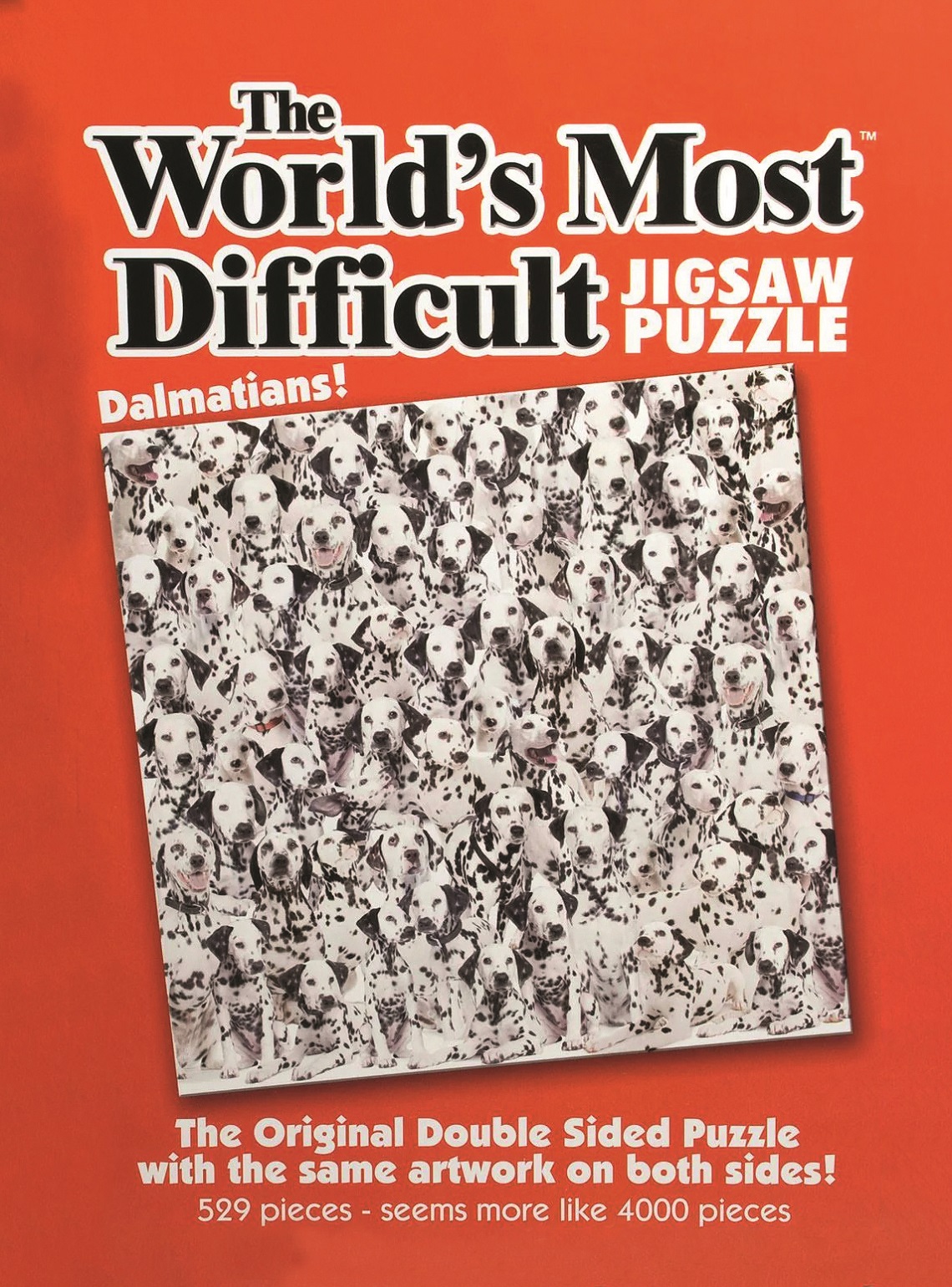

- A 529-piece, double-sided jigsaw showing dozens of dalmatians is billed as the world’s most difficult puzzle

- The individual 2023 World Jigsaw Puzzle Championship was won by Spaniard Alejandro Clemente León, who finished a 500-piece puzzle in 37 minutes 59 seconds

Credit: Hamptons

'The second cosiest cottage in Britain' is on the market in Wiltshire

With its attractive period features and impeccable styling, this chocolate box home has already caught plenty of media attention. It’s

10 ways to insulate a period property

Modern technology might offer sustainable, cost-effective heat sources, but the best-value unit of energy is the one you don’t lose

When did Stir-up Sunday first begin?

On the last weekend before Advent, families gather to make Christmas pudding on the day we know as Stir-up Sunday.

Ben Lerwill is a multi-award-winning travel writer based in Oxford. He has written for publications and websites including national newspapers, Rough Guides, National Geographic Traveller, and many more. His children's books include Wildlives (Nosy Crow, 2019) and Climate Rebels and Wild Cities (both Puffin, 2020).

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life