The technique used to make the Bayeux Tapestry is back in fashion after 950 years

Most famously used to create the Bayeux Tapestry, crewelwork is enjoying a revival, says Giles Kime.

Before its demise during the pandemic, my son and I stayed at the gatehouse at Sharrow Bay in Cumbria, which is due to reopen next year. When it launched in 1948, it was the first hotel to be described as ‘country house’ and, by the time we stayed, it was definitely of the charmingly threadbare variety, with ancient chintz curtains as thick as duvets and quilted counterpanes. It evoked a lost world of mothballs, Hinge and Bracket and lapsang souchong. Bliss, in other words. (Another highlight was a plaque that commemorates the day Lord Cameron launched himself into Ullswater from its bank.)

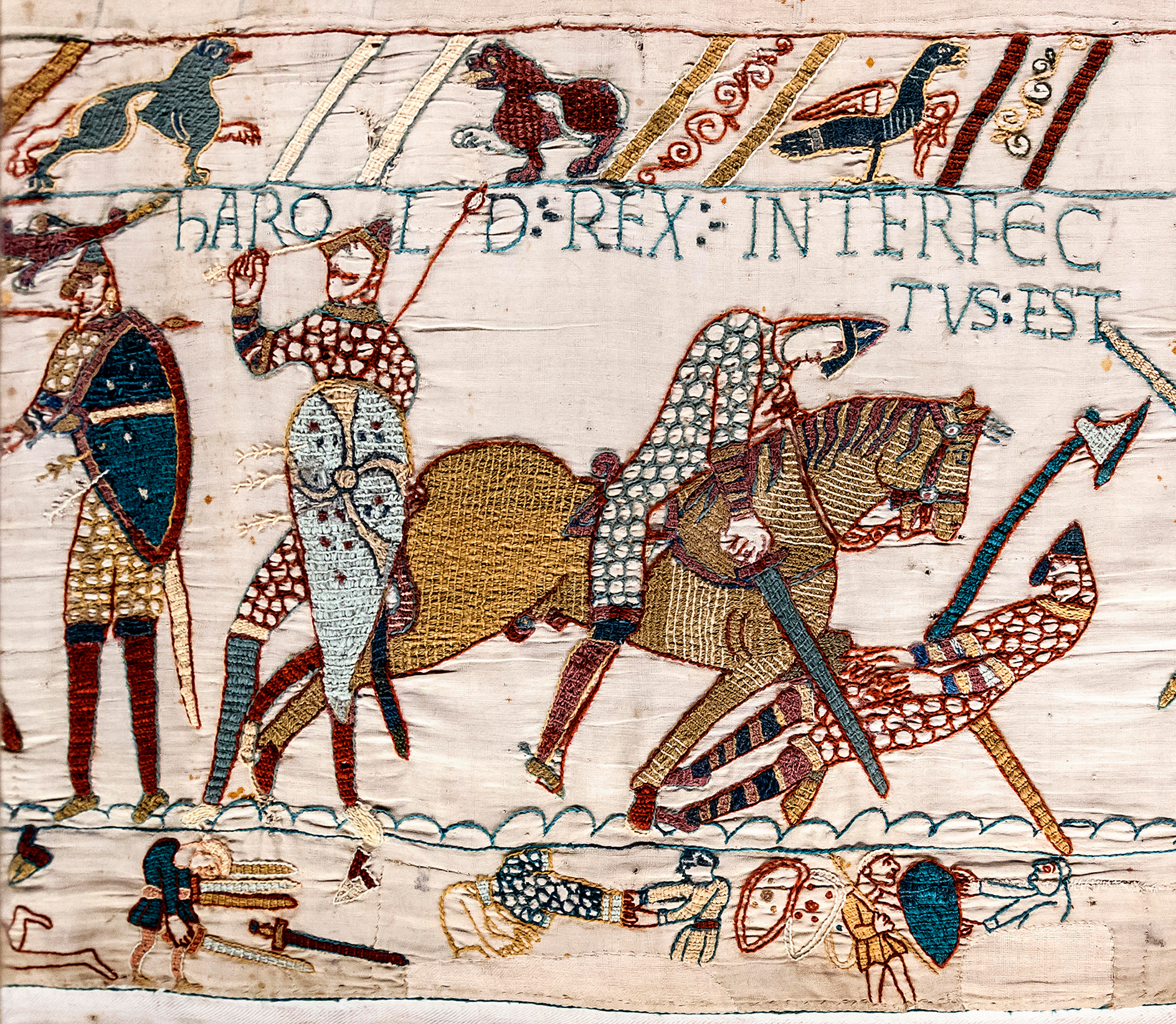

‘Posh granny’s spare room’ is an endangered vibe, but elements are being revived; needlepoint stools, loose covers, lustreware and now, out of the blue, comes crewelwork, the embroidered fabric that was for centuries a staple of the English country-house aesthetic. The technique — which involves the surface embroidery of wool, usually on linen — is commonly associated with 16th- and 17th-century Britain and later New England. Its roots, however, go way back to the 11th-century when, as every skool boy kno, it was used to create the Bayeux Tapestry, rather than actual tapestry, which is a wholly different process involving weaving coloured weft threads through plain warp threads.

Although crewelwork is more labour intensive than printed textiles, it has a three-dimensional quality and exquisite detail that lends itself particularly well to figurative and botanical motifs. The use of white wool on a coloured background, such as those fabrics available at both Susie Watson and Coromandel, creates a softer, more contemporary feel.

The chief difference between an unreconstructed English country house and its evolving 21st-century incarnation is a degree of restraint that can cast elements such as beautiful textiles and crewelwork in a fresh, new light. Many of the rooms at The Bell in Charlbury, Oxfordshire, that opened last autumn have been decorated with examples of both new and restored crewelwork, which lend the spaces a wonderful handcrafted, homespun quality. The intricate work was carried out by the London-based designer Sarah King, who clearly demonstrates that, almost a millennium after the creation of the Bayeux Tapestry, the technique is not only alive and well, but also relevant to a wide number of different aesthetics.

Westminster Abbey: 1,000 years of coronations, from King Harold and William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II and Charles III

The setting of Charles III’s crowning in Westminster Abbey in London lends grandeur and history to this great ceremony. John

Pevensey Castle, East Sussex: The Roman castle that was still being used in World War II

When William the Conqueror landed at Pevensey, he moved in to the nearby castle — one which had already stood for

Credit: Getty Images/EyeEm

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Jason Goodwin: The night I accidentally sent a friend to go dogging on a remote West Country hilltop

Oh, Jason. It could have happened to anyone.

-

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham Dockyards

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham DockyardsAn antique dealer with an eye for colour has rescued an 18th-century house from years of neglect with the help of the team at Mylands.

By Arabella Youens

-

You're having a giraffe: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 25, 2025

You're having a giraffe: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 25, 2025Friday's Quiz of the Day brings your opera, marathons and a Spanish landmark.

By Toby Keel