Still on a roll: Fabrics and wallpaper that have stood the test of time

Arabella Youens identifies the patterns that survive from the great flourishing of 19th-century decoration.

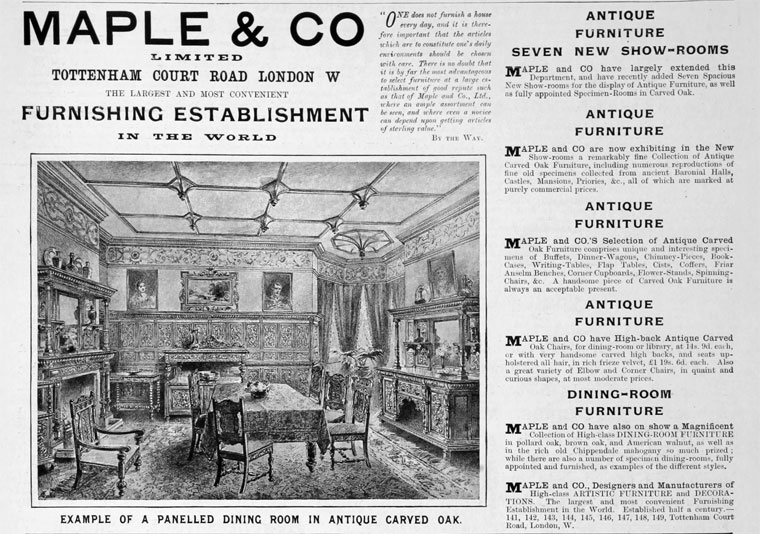

Today, it’s a busy thoroughfare that’s being excavated in the name of Crossrail, but, in the 1860s and 1870s, Tottenham Court Road was the beating heart of Victorian London’s burgeoning interiors industry. Heal’s, the sole survivor from that era, rubbed shoulders with now long-lost names such as Oetzmann, Shoolbred and Maple & Co, which all had their flagship stores here.

The latter boasted a shopfront that stretched the equivalent of 25 houses. By the time Country Life was launched, home furnishing was big business: in 1897, Maple generated a profit of £284,000 and went on to open shops in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

The interest in, and affordability of, domestic decorating was relatively new: both were by-products of wealth generated by the Industrial Revolution and the mechanics that made the cost of elements such as wallpaper more affordable. At the time of Queen Victoria’s ascension to the throne, domestic interiors were dominated by a dark, brooding palette of colours, swathes of velvet and souvenirs from travels on every available surface.

By the twilight years of her reign, however, attitudes were changing fast. In 1868, Charles L. Eastlake published his Hints on Household Taste, which was to become one of the era’s most influential volumes on all aspects of the domestic interior, calling for people to buy well-crafted pieces to create simpler, pared-back schemes.

Another major influence was the advent of electric light, which shone an unflattering glare on the ingrained dirt in Victorian houses, leading to the popularity of machine-printed fabrics and wallpapers that were relatively inexpensive and easy to replace.

Perhaps a backlash was inevitable. The birth of the Arts-and-Crafts movement, under the influence of which Country Life was born, saw a reaction against technological advances and set out to revive the craftsmanship and simpler styles of the Middle Ages. It seems no accident that most of the fabric and wallpaper firms that survived are those that embraced and championed craftsmanship.

WARNERS

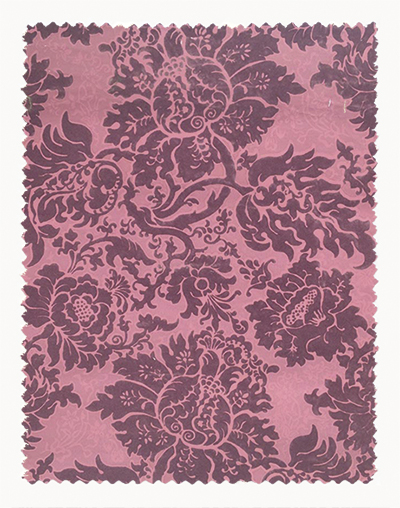

Established by the descendent of a Spitalfields-based Hugue-not scarlet dyer, this family-run firm became one of the most important silk-weaving companies of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By the early 1890s, and after buying up several (sometimes older) competitors, what had then become Warner & Sons moved to Braintree in Essex and went on to weave silk and velvet for English Coronations as well as supplying palaces, ocean liners (among them Lusitania) and large country houses.

By 1971, however, production had stopped altogether in Braintree due to the prohibitive cost of hand weaving and greater competition, but the substantial archive of designs, which date back to 1752 (many inherited during its period of acquisition in the early days), was bought by Braintree District Museum in 2004, with grants from the Heritage Lottery Fund and others.

Last year, the archive celebrated the launch of its first textile range at the London showroom of Claremont Furnishing Fabrics, based on 12 designs selected to reflect the diversity and quality of the collection. Printed by the French mill Tissus d’Avesnières, the collection revived a number of designs, including several that would have been available to Country Life’s first readers, such as Coral, taken from an original hand-printed chintz dating from the 1870s, and an exquisite, ageless floral chintz called Eleanor, which dates from the 1860s and has been reprinted using the traditional hand screen-printed method in the original document colours.

WATTS OF WESTMINSTER 1874

In the year that Country Life launched, George Gilbert Scott (known as ‘Middle Scott’) died in the St Pancras Hotel, which had been designed by his father, the prolific English Gothic revival architect Sir George Gilbert Scott. Middle Scott, together with two other practising architects, founded Watts in 1874 to supply the entire range of interior furnishings for both houses and churches; more than 140 years later, one of the firm’s directors is Middle Scott’s great-great-great-granddaughter, Marie-Séverine de Carman Chimay.

The success of the company was boosted by a series of important commissions for church, state and civil ceremonial purposes, much of which was thanks to the work of Elizabeth Hoare (née Scott), whose charm, tenacity and instinct steered the company through the highs and lows of the post-Second World War period and who never thought that Watts would give in, as Ilse Crawford wrote in the World of Interiors, ‘to the demands of wash ’n’ wear’.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, luxurious interiors around the world were dressed by Watts (now Watts of Westminster), from the Mandarin Oriental in Hong Kong to the homes of Bryan Ferry and Andrew Lloyd Webber. In 2014, the original hand-carved pearwood blocks were restored in order to return to the company's producing all wallpaper as hand-block printing.

SANDERSON

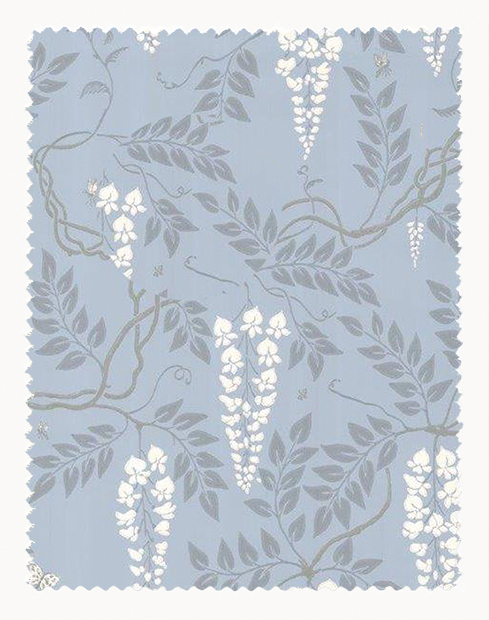

The oldest surviving brand name in its field was established in 1860 by Arthur Sanderson in Islington, London. Originally an importer of French wallpapers, he later moved to Berners Street in Soho (where the showroom remained until 1992). He began to commission designs by block printers in England. Arthur’s sons, who inherited the firm, were early adopters of innovation and introduced printing machines to their factory in Chiswick and the company was awarded a Royal Warrant in 1923 and again in 1955, to supply wallpapers, paints and fabrics to Elizabeth II.

The company, now based in Denham, Middlesex, continues to uphold many of the tenets set out by its founders. Wallcoverings are manufactured in Anstey, Leicestershire, where modern machine-printing presses work alongside hand-block and silkscreen printing production—it’s one of the few remaining companies still producing hand-printed wallcoverings.

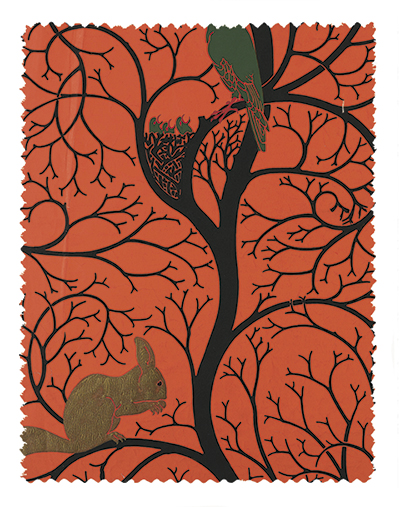

As part of the company’s 150th anniversary in 2010, a design by the architect and textile designer Charles Voysey, Squirrel & Dove, which was first produced in the 1890s, was brought back into the range as both a fabric and a wallpaper.

COLE & SON

Founded by John Perry in 1875, the company has provided wallpapers for a number of notable houses, including Buckingham Palace and the Houses of Parliament, where A. W. N. Pugin’s Gothic Lily paper still hangs. Originally based in Islington, a centre for block printing in London, John Perry and his successors spent the latter part of the 19th century printing for more established firms such as Jeffrey & Co and Shand Kydd.

When the company was bought by A. P. Cole in 1941, then adopting the name Cole & Son, it inherited the largest archive of historical wooden printing blocks in the country and the showrooms and offices moved to Mortimer Street—not far from Tottenham Court Road. Today, as part of its bespoke service, clients are able to delve into the formidable archive to produce faithful reproductions of a historic design. The company has also launched its Archive Traditional collection of 12 designs—some of which hadn’t seen the light of day for many decades. These include Ludlow, which is an 18th-century design taken from a fabric created for the Williamsburg Colony, and Dialytra, a flowing leaf design from the early Victorian period.

LIBERTY & CO

Arthur Liberty began his career as an apprentice to a draper and opened his business in 1875, which he named East India House, where he sold Oriental fabrics that quickly became popular for their soft texture and vibrant colours. As demand for the fabrics grew, Liberty made the decision to import undyed fabrics and have them hand-printed in England. It was during the late 19th century that the designs focused less on East Asian elements and more on the quintessentially English floral prints for which it was to become known.

Liberty’s clientele always erred on the side of bohemian: ‘Liberty is the chosen resort of the artistic shopper,’ quipped Oscar Wilde (who is credited for introducing the brand to the Americans during a visit in 1882). Classic designs by William Morris were successfully resurrected in the 1950s and others from the Art Nouveau period were redrawn and coloured to form the Lotus Collection in the 1960s.

MORRIS & CO

William Morris and the Arts-and-Crafts and Aesthetic movements trail-blazed simplicity, craftsmanship and design inspired by Nature, but it was after building and decorating his first home, Red House in Bexleyheath, which was designed by his friend the architect Philip Webb, that Morris decided to turn what had hitherto been a domestic hobby into a commercial enterprise. Although, in their early days, the group set about making a collection of stained glass, furniture and tapestries, it was the ‘wallpaper hangings’ that were the most popular.

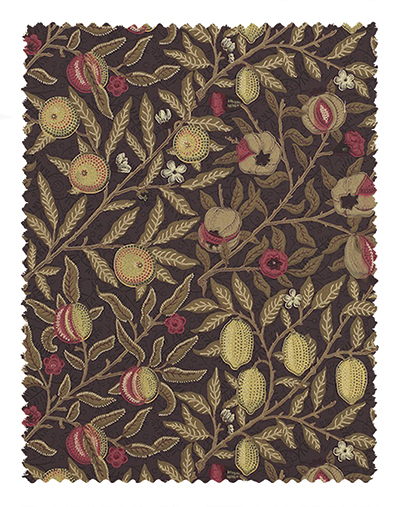

In the late 1860s, Morris concentrated on wallpaper and textile designs; his first three repeating wallpaper patterns were Trellis, Daisy and Fruit—their popularity continues to this day. By the 1880s, and after buying the company out, Morris & Co’s chintzes, damasks and cotton prints were being sold throughout the world. Morris died the year before Country Life was founded and his company’s fortunes subsequently went through good years and bad until Sanderson bought it in May 1940 (somewhat improbably during the evacuation of Dunkirk), under whose patronage it remains today.

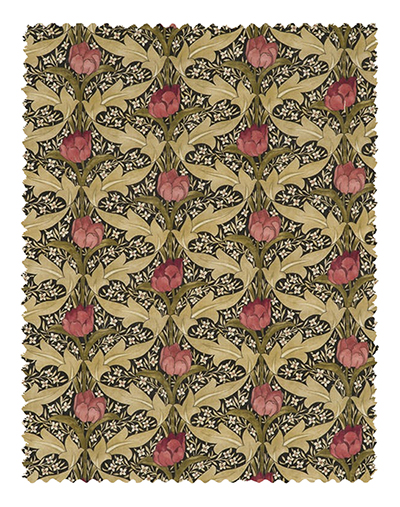

G. P. & J. BAKER

Founded in 1884 by brothers George Percival and James Baker, whose father designed the British Embassy gardens outside Constantinople, the business initially focused on importing Persian, Turkish and Turkoman carpets, before expanding into textiles. After buying the renowned Swaisland Fabric Printing Company and gaining its archive, which dated back to the 18th century, the company employed leading Arts-and-Crafts designers to build on the collection. Some of the most popular designs were printed in the early 1900s showing English garden flowers—a style for which the company is still known today.

The Baker Archive is the world’s largest privately owned textile archive, ranging from Chinese wallpapers to Italian velvets, French toiles and Indonesian batiks. Today, the design studio regularly dips into the archive for inspiration and the Baker Originals collection features long-established classics, dating back to the 18th century, such as Ferns, Nympheus and Magnolia, which have been reworked and recoloured in a modern palette.

The best interior designers in Britain

Of all the decorating trends that have been in vogue over the last 50 years – be it Scandi, Minimalism

Love letters from our readers: Famous fans of Country Life

We ask friends of the magazine to tell us what keeps them turning our pages.

Beautiful bedding ideas for a luxurious night’s sleep

The simplest way to infuse colour, pattern and texture into your bedroom.

10 things you didn’t know about French bulldogs – including how they’re actually British

Elizabeth Whitney reveals some fun facts about the endearingly bat-eared French bulldog.

-

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day blows smoke, tells the time and more.

By Toby Keel

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon

-

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire garden

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire gardenDesigners from Sanderson have immersed themselves in The King's garden at Highgrove to create a new collection of fabric and wallpaper which celebrates his long-standing dedication to Nature and biodiversity.

By Arabella Youens

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's Breath

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's BreathBy Carla Passino

-

The power of the youthful gaze: A new generation tackles modern day design conundrums

The power of the youthful gaze: A new generation tackles modern day design conundrumsHow is a new generation of interior designers responding to changing lifestyles, proliferating choice, the challenges of sustainability and the tireless demands of social media?

By Arabella Youens

-

'Rooms can be theatrical and comfortable at the same time': Top tips for decorating with conversation in mind

'Rooms can be theatrical and comfortable at the same time': Top tips for decorating with conversation in mindCarefully placed furniture encourages conversations, says Emma Burns, of Sibyl Colefax & Fowler

By Country Life

-

A tub carved from a single block of San Marino marble — and nine more beautiful things for the ultimate bathroom

A tub carved from a single block of San Marino marble — and nine more beautiful things for the ultimate bathroomThere's a bathroom out there for everyone — whatever your preferred style.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

In search of the perfect comfy armchair

In search of the perfect comfy armchairWhat makes the ideal cosy, comfortable armchair? Arabella Youens asks some of Britain's top furniture experts to find out.

By Arabella Youens

-

All the new entries in the Country Life Top 100 for 2025

All the new entries in the Country Life Top 100 for 2025Each year, our Country Life Top 100 is completely revised and updated — and several new names appear.

By Country Life