In Focus: How Pimlico went from Mozart's playground to a world-famous hub for design and antiques

London’s premier design district is home to some of the world’s leading interior-design and furnishing shops, but its refined façades belie a bohemian past, as Carla Passino discovers.

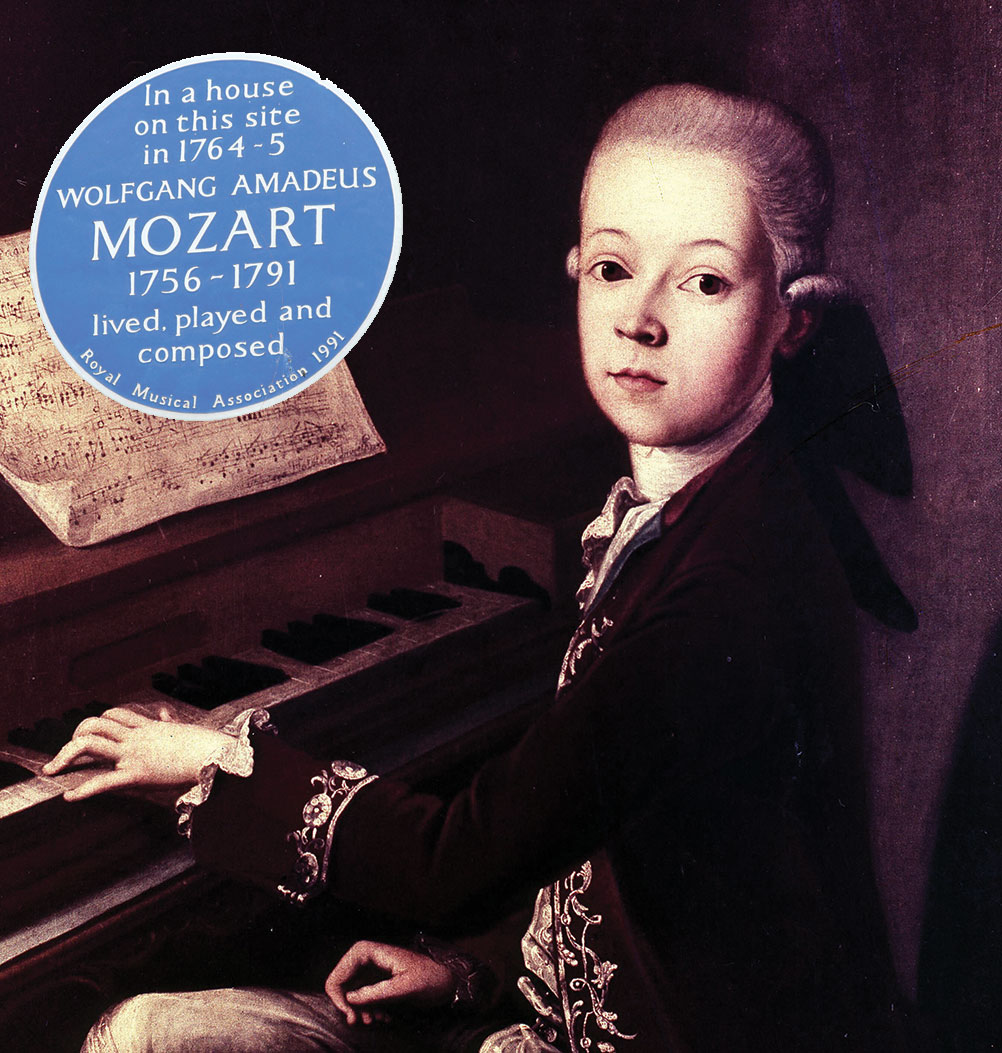

The bronze of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart proudly surveys Orange Square, off Pimlico Road, with a slightly cheeky look on his chubby face. Unveiled in 1994, the statue pays tribute to the Austrian genius who composed his first symphony, aged only eight, when staying at a house up the road (180, Ebury Street). Although Mozart is perhaps their most famous (if rather ephemeral) resident, the streets around Pimlico Road have been home to an array of colourful characters who have given this corner of London a unique identity.

At the time the Mozarts settled in Ebury Street, the area had a distinctly rural feel, not least because it was bordered to the east by Neat House’s market gardens, about 200 acres brimming with the cabbage, celery, cauliflower and asparagus that kept London fed.

In one of the streets that lined the gardens (now Warwick Way), resided one of the Regency era’s most notorious villains — Slender Billy. Thief, forger and a well-known organiser of badger-baiting and dog-fighting encounters, he nonetheless ‘bore the reputation of a man of strict probity in his nefarious dealings,’ according to the 1825 edition of Sporting Anecdotes — so much so that, when he was hanged on January 29, 1812, his passing was much mourned.

Far more distinguished personages frequented an establishment at the western end of the Pimlico Road area — the Chelsea Bun House, which later became a favourite with Georgian London. Never was trade brisker than on Good Friday, when tens of thousands of people flocked to the shop for hot cross buns, often requiring ‘a number of constables to keep order,’ according to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (on the Good Friday of 1839, the shop sold 24,000 buns).

Another notable establishment, Chelsea Barracks, opened in 1862 as the new home for two infantry battalions. The original, imposing building lasted less than a century before it was replaced by two unsightly tower blocks.

Time made justice of the eyesores and the Barracks is now one of the capital’s most prestigious new developments, centred on a contemporary reinterpretation of Belgravia’s garden squares.

Nonetheless, with their skyline-blighting architecture and their rowdy reputation both helping keep a lid on local rents, the 1960s barracks may have unwittingly accelerated the radical transformation that would forge Pimlico Road’s identity as London’s ‘design district’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It all started with a trickle — a handful of brilliant, often eccentric antique dealers who set up shop in an offbeat, relatively inexpensive area. ‘The rents were cheap and the road was unsmart. It was slightly raffish and that’s what gave it its charm,’ says Wendy Nicholls of Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler.

"There was something lovely about its shambolism"

Many of the early grandees combined theatrical grandeur with a bohemian streak, and none more so than Geoffrey Bennison, ‘a flamboyant character whose aesthetic genius set the tone,’ according to Will Fisher of Jamb. Mr Bennison would even employ people on a whim if they caught his imagination: marble mason Roy Carter — whom Mr Fisher describes as ‘an Adonis even at the age of 75’ — was hired on the spot when the fabled decorator saw him digging the road, shirtless, as he passed by in his chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce.

‘The car screeched to a halt, then reversed back,’ Mr Fisher recalls Mr Carter telling him. ‘Geoffrey looked down at Roy, topless, toiling in the dirt and said, “Well, lovey, what do you get paid for digging these days?” Roy replied: “Five shillings a week.” Geoffrey said: “If you fancy making five times that, you’ll jump in the back of the Rolls.” With that, Roy threw down his shovel and off they drove.’

Lulu Lytle of Soane Britain recalls, ‘a magical street dominated by legendary antique dealers. It was a hub for runners, the dealers that didn’t have their own shop, and it was lined with beaten-up old Mercedes and Volvos with their boots up, showing wonderful pieces of furniture. Those were mad days but it was fabulous’. Time has changed Pimlico Road, making it ‘more professional and grown-up,’ but a wistful Mrs Lytle says that ‘there was something lovely about its shambolism’.

There’s perhaps one moment that, more than any other, captures the essence of the street and the friendships bonds that are formed along it. The 1981 funeral procession of Terry Green, Geoffrey Bennison’s manager and right-hand man, which, recalls Gillian Newberry of Bennison Fabrics, ‘was complete with carriage, ostrich-feather-plumed black horses and a top-hatted man slowly walking in front with a silver-topped cane. The whole street came out of their shops and stood to attention on the kerb as the cortège passed by’.

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.