Totally tropical Tresco: The English country garden that brings the tropics to the British Isles

A warm reception awaits visitors to Tresco Abbey Garden — the home of Robert and Lucy Dorrien-Smith — where the year-round temperate climate has created an extraordinarily colourful garden–even in winter. Tiffany Daneff reports, with photography by Clive Nichols.

Few gardens have their own heliport, yet this is far from the most remarkable of the many extraordinary features of Tresco Abbey Garden, 28 miles off the coast of south-west Cornwall, which, for most people, can only be reached after travelling for the best part of a day.

Its history, of which more later, encompasses five generations of one determined and unusually focused family. Its geography — it sits on the southern end of Tresco Island, which itself is only two miles long and forms part of the archipelago of 200 islands, islets and rocks that form the Isles of Scilly — gives it a year-round temperate climate, enabling plants from South Africa, South America and the Mediterranean to thrive. (At the New Year’s Day count in 2024, 287 different species were in flower.) And what dramatic and rare species they are! To English eyes, more accustomed to the gentle softness of pinks and lilacs, the abbey garden delivers a knockout punch; like discovering Pucci after Laura Ashley.

From the moment you arrive on the island, you’ll spot escapees from the garden. The granite walls that thread across Tresco are alive with giant yellow-flowering aeoniums, little yellow oxalis and crimson and scarlet lampranthus. Brilliant-pink Gladiolus byzantinus pop up on field edges, 6ft-tall echiums rise up from cottage gardens and the sand dunes of Pentle Bay are fringed with great drifts of the purple daisy flowers of Senecio glastifolius, a South African native. In place of thorn and maple, many hedges on Tresco are planted with Olearia traversiorum, a fast-growing and salt-tolerant plant from the Chatham Islands in New Zealand. The gleaming rich-green leaves of Coprosma repens, commonly known as the looking-glass plant, also make hedges so shiny they stop one in one’s tracks. Even when the sun isn’t shining, it is impossible not to smile.

The distinctive red bracts of Beschorneria yuccoides with purple Senecio glastifolius that has self-seeded around the island.. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

To the Abbey Garden itself, begun in 1834 by the indefatigable Augustus Smith, a gentleman from Hertfordshire with the means to take a 99-year lease on the Isles of Scilly from the Duchy of Cornwall for £40 per annum. The quid pro quo was that, as Lord Proprietor (the title he thus acquired), he would invest £20,000 in the islands’ development. As his many doings on the island to create jobs and provide schooling are not part of this story, suffice to say that, having decided to build himself a home on Tresco — the most sheltered and accessible island — he chose a spot beside the ruins of the 9th-century priory of St Nicholas, of which little remained except two stone archways, now encrusted with succulents. To counter the salty gales that blew in from the Atlantic, he had 12ft-high walls built and planted the hillside with a variety of trees, of which the Californian Monterey cypress, Cupressus macrocarpa, and Monterey pine, Pinus radiata, proved most resilient to the salt-laden winds.

The layout of the garden — which remains the same today — was of three walkways running east to west along a top, middle and lower terrace with paths leading up and down between them and a series of steps, from the bottom of the garden to the top, arriving at the statue of Neptune, a figurehead from one of the many ships wrecked in the treacherous Scillonian waters. (Smith’s original collection, since augmented, can be seen in the Valhalla Museum in the garden.)

The bromeliad, Puya x berteroniana. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

The foundations established, there followed the great business of filling the garden, which Smith did by looking to Australia, South Africa and Mexico and making special areas in the garden for different countries. A photograph of him in the museum at the entrance to the garden reveals a stout figure tightly buttoned in a mariner’s coat and naval cap, appreciating a Puya chilensis that towers above him. The sepia image doesn’t convey the exoticism of this statuesque plant, which grows to 8ft high — some forms have surreal jade-coloured flowers with anthers coated in bright-orange pollen.

Many examples of this native Andean bromeliad grow in the garden today. Instead of hummingbirds, they are pollinated by blackbirds and starlings — and sometimes red squirrels, which have been successfully introduced to the garden with no greys on the island (nor, indeed, are there foxes, badgers, snakes, frogs or toads).

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Every inch of this terrace wall has been colonised with succulents, aeoniums and colourful lampranthus.. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

The plant collecting went up a gear when Maj A. A. Dorrien-Smith inherited Tresco in 1918 from his father Thomas Algernon (Smith’s nephew and heir). The major was already a keen plantsman and, during his time in the Boer War, had sent plants back to his father from the veldt. The appearance of Metrosideros lucida in the garden (another tree that proved able to withstand the salt), as well as the coprosma and olearia, date from this time.

For their honeymoon, Dorrien-Smith and his wife, Eleanor, went camping in the Stirling Mountains of Western Australia, where they were thrilled to see acacias (of which there is now a National Collection in the garden), kangaroo paw plants, Anigozanthos manglesii, eucalyptus, sisyrinchium and many, many others. Plants were shipped back in specially made cases — on one trip, the major was accompanied by 2,000 potted specimens, as well as thousands of seeds.

By the 1920s, there were 16 gardeners — today, there are eight — and entry to the thriving garden was free of charge. Disaster struck, however, in 1929, when storms brought down 600 trees, which crashed into and destroyed many other plants. Yet, thanks to Tresco’s climate, by 1935 a list of the plants in the garden numbered 3,500 species and cultivars. As now, they were planted with South African, Australian and Mexican species on the Top Terrace, with its poor shallow soil that sits only a few inches above the bedrock. Mediterranean and Canary Island plants enjoy the slightly deeper soil and better protection of the Middle Terrace, where the present inhabitants of the Abbey, Robert Dorrien-Smith and his wife, Lucy, have made a lovely terraced Mediterranean Garden with a shell house and fountain.

A red squirrel visits a Puya chilensis. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

Among the most popular plants are the proteas, of which the first were brought back by Lt-Cmdr Dorrien-Smith on a trip to the Cape in 1969. (He also brought home aloes, galtonia, gladiolus, watsonias and the pincushion plant Leucospermum cordifolium, another favourite with its plasticky orange flowerheads and stemless leaves.) So big, bold and colourful are the plants in the garden and so alien in their forms from our native species that even those who think they aren’t interested in plants will be drawn to the monstrous succulents, such as dasylirion, with spiky-edged leaves that can grow to as much as 4ft and take almost spherical forms.

This Clianthus puniceus flowers on New Year’s Day. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

One old specimen on Tresco has grown as it would in the wild, forming thick trunks that snake across the ground in an almost animalistic way. Another favourite is Sonchus brassicifolius, also known as the Robinson Crusoe cabbage (with leaves that can reach 18in long), which is what Alexander Selkirk ate when stranded on the Juan Fernández Islands.

Keen plantsmen can lose themselves for days in admiration of the red-flowering Eucalyptus ficifolia; the Norfolk Island pine, Araucaria heterophylla; the New Zealand Christmas tree, Metrosideros excelsa; the banksias, palms and abutilons; 6ft-tall tree dandelions Sonchus arboreus from the Canaries; and still leave knowing that there is much more to see.

The view from the top terrace down the Neptune steps, flanked by Canary Island palms, to the sea beyond. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

To be employed as a gardener here is surely to be in heaven, albeit with a lot of work to do. Head gardeners tend to stay for decades and Mike Nelhams, who first came on a student scholarship in 1976, returned as head gardener in 1983 and became curator in 1994 when his colleague Andrew Lawson — who began as propagator in 1985 — took over. Together, they witnessed the two greatest disasters in the garden’s history: the snow storm of 1987 that destroyed whole collections, turning much-loved specimens to foul smelling heaps of rotting material, and was followed, too painfully soon, in 1990 by a 127-mile-an-hour hurricane that dumped seawater on the garden and ripped through the shelter-belt, destroying 90% of the 130-year-old trees in only four hours.

The horticultural world is very generous in times such as these and, when it came to restocking the gardens in 1987, the great botanic gardens at Edinburgh and Port Logan, Dumfries & Galloway, offered many replacements for lost specimens, as did the garden at Inverewe in Wester Ross, where Peter Clough, former head gardener at Tresco for 12 years, was then based. Kew was invaluable in the garden’s renaissance, too, giving quantities of surplus stock and cuttings, as did several private gardens and other collections, many of them in Cornwall. Getting the plants to Tresco was a mammoth task, involving transportation via lorries to Penzance and then transfers to containers for shipping to St Mary’s, followed by smaller ships to Tresco, where tractors and trailers took the precious loads to the Abbey Garden. Thankfully, Mr Nelhams recalls in his book Tresco Abbey Garden, ‘our monthly temperatures mean that we were able to plant at almost any time of the year’.

Leucospermum cordifolium. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

Planting had only recently been completed when the hurricane struck, bringing new chaos as the mature trees fell, crushing other plants and destroying the outer walls (letting in rabbits). The hillside was ravaged with 20ft-high upended rootplates among the debris. To give an idea of the scale of fallen trees, Mr Nelhams recalls that the route along the hillside that usually took 10 minutes to traverse took two hours. Following the massive clear up, 10,000 new trees have been planted by the team with the support of the Dorrien-Smiths and, 30 years on, these have matured well, creating an effective new shelterbelt, although the handful of noble survivors of the hurricane still top them by 15 or so feet.

Last year, Adam Dorrien-Smith, representing the sixth generation, took over the management of Tresco and, although the garden is looking better than ever — with a new visitor centre featuring timelines and photographs of the garden’s story — no one is taking any risks. Spare seedlings are carefully collected and raised by the garden propagator Emma Lainchbury and the work of sharing surplus stock with other botanic gardens and Cornish gardens continues, ensuring that, should any plant die, there will always be a replacement.

Visit www.tresco.co.uk

The writer flew to Tresco courtesy of Penzance Helicopters (www.penzancehelicopters.co.uk)

A rare yellow-flowered Euphorbia stygiana from the Azores borders the lower path. ©Clive Nichols Garden Pictures

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon

-

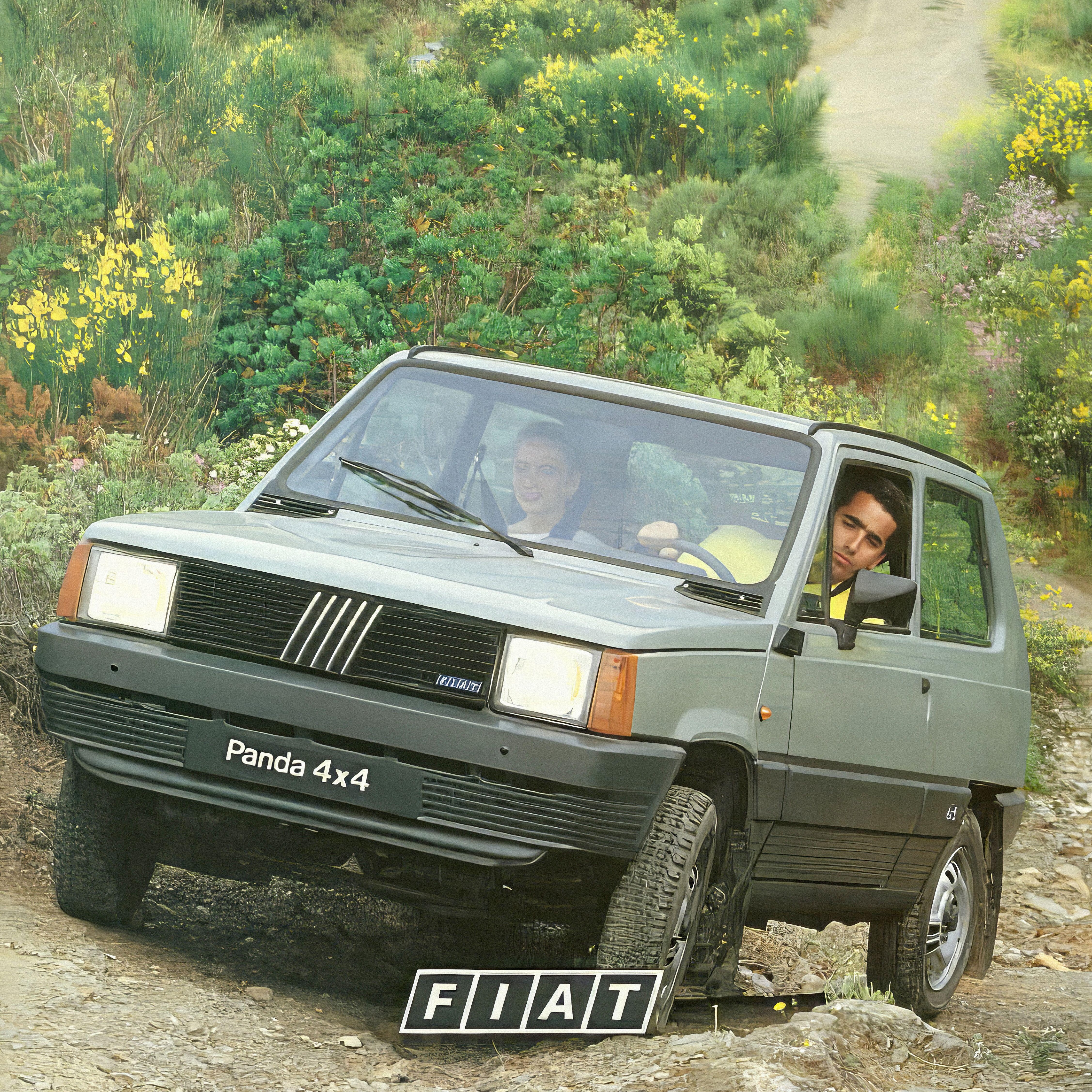

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classic

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classicGianni Agnelli's Fiat Panda 4x4 Trekking is currently for sale with RM Sotheby's.

By Simon Mills