The gardens of High Moss, a Cumbrian paradise just moments from Derwentwater

Non Morris visits the much-loved gardens of High Moss, in Portinscale, Cumbria — home of Peter and Christine Hughes — and finds a historically fascinating Arts-and-Crafts garden which has been imaginatively brought back to life. Photographs by Val Corbett for Country Life.

High Moss, an imposing white house with a distinctive double-gabled roof, looms splendidly at the very top of its steeply terraced garden. From the south-facing rear, there are exhilarating 180˚ views out to craggy Grisedale Pike and Catbells. From the bottom of the garden, it is a mere five-minute walk to the gorgeous expanse of Derwentwater itself; to see it for yourself, High Moss is open in aid of the Red Cross on May 19,2024, from 2.30pm–5.30pm.

The key quality of an Arts-and-Crafts garden is its close relationship to the house. As Peter and Christine Hughes began to unravel the history of their home and breathe new life into its tired terraces, they became utterly bound up with the project. For Mr Hughes, the challenge of restoring the garden has led to a Masters in Garden History and, since 2020, the chairmanship of the garden-history and conservation charity the Gardens Trust.

Work began on the 4½ acres of garden six months before the couple moved here in 2009. As they were renovating the house and coming to terms with the way it is spread over multiple levels to cope with the steepness of the site — ‘it’s all half landings,’ notes Mrs Hughes — they were delighted that experienced local gardener Tom Attwood came to help. The plan was to note existing plants, working outwards from the house, but it was not long before entire borders were stripped and replanted.

The garden, which had been in the same family for 61 years, had been maintained rather than gardened by a team of contractors. The opening for more radical intervention came when a pair of cottages at the bottom of the garden were re-roofed just before the Hughes arrived. The only way for the builders to get to the cottages was to cut their way through a mass of overgrown rhododendrons.

As swathes of Rhododendron ponticum and gorse were removed, the challenge of planting replacements on this steep ground revealed itself. On the upper slopes nearest the house, there are banks baked by the sun, with thin, acidic, shaley soil. The owners created organically shaped beds, constantly mulched to improve growing conditions. They also planted small azaleas and rhododendrons and spreading groundcover roses, which are establishing well.

Lower down, the cleared beds that divide the terraces of the garden were filled with richly coloured species rhododendrons and flowering trees, such as Cornus kousa var. chinensis and C. mas. Hydrangeas are invaluable for creating soft massed effects later in the season, with, everywhere at their feet, wonderfully healthy mounds of hosta.

Lower still, in the previously congested woodland, the mood changes completely. Here, winding paths have been created to lead you past an enchanting Halesia carolina (Carolina silverbell) or through a tunnel of ancient-looking rhododendrons, which have had their crowns lifted to celebrate their gnarled trunks. ‘It’s magical to walk here when the ground is a carpet of magenta petals,’ says Mrs Hughes. Planting in this area is tough going. Mandy Caddy, who has gardened at High Moss for the past nine years, explains ‘the most useful tool here is a little hand mattock, as the ground is so hard and full of tree roots’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Beyond this feeling of gentle enrichment and replenishment, Mr Hughes confirms that ‘the infrastructure is almost entirely as it was originally in 1902’. At one end of the house, the dilapidated conservatory was immaculately restored by Hartley Botanic and, at the other, a sheltered loggia was released from an unsatisfactory sunroom: both confirm, of course, the link between interior and garden. The long terrace is particularly charming, with its own lookout bastion. It leads to the original steps, which stretch to the bottom of the garden and nestle between dry-stone walls and hedges of box and beech brimming with textured shady planting: delicate ferns, brunnera and Japanese anemones.

Mr Hughes has relished opportunities for being faithful to the Arts-and-Crafts spirit. The diamond motif found in the decorative detail of the house is echoed in garden gates and even the kitchen garden has been laid out in a diamond formation. Mrs Hughes is aware that her husband would love to create further garden rooms, but, for her, the spacious and deliciously empty Big Lawn — the former croquet lawn and tennis court — is crucial. It is a magnet for their grandchildren and often home to the village garden party.

The garden at High Moss has myriad moods, being small enough to feel intimate and large enough for a ‘proper walk’. During lockdown, the Hugheses had a picnic in a different part of it every day. This much-loved, historically fascinating garden has now been carefully and imaginatively brought back to life.

High Moss, Cumbria, opens in aid of the Red Cross on May 19, from 2.30pm–5.30pm

A brief history of High Moss

‘High Moss is one of the many successful little houses which have been built to Mr W. H. Ward’s designs by Derwent-water.’ This is how a ‘Lesser Country Houses of Today’ Country Life article of 1913 set the scene for this important Arts-and-Crafts summer house, which was built in the increasingly fashionable Lake District in 1901–02.

It was commissioned by John Stanwell Birkett, a successful London solicitor and National Trust Council member with an avid interest in the Arts-and-Crafts Movement. Although built for Birkett’s own use, his original plan was to develop a small estate of Arts-and-Crafts houses. The idea was never realised — perhaps because the busier south end of the Lake District, around Windermere, was more accessible by train.

Architect William Henry Ward (1865–1924) was a protégé of Arthur Blomfield and worked for the London firm George and Peto (the ‘Eton of architects’), before returning to the Lakes to work with Dan Gibson and then going back to London to join Edwin Lutyens. Gibson had worked briefly with Thomas Mawson (1861–1933), the prolific designer, whose 1900 The Art and Craft of Garden Making defined the role of the landscape architect for the first time. Mawson believed that the design of a garden should closely relate to the architecture of the house, that it should celebrate the natural character of the landscape, employ local materials and include vernacular details.

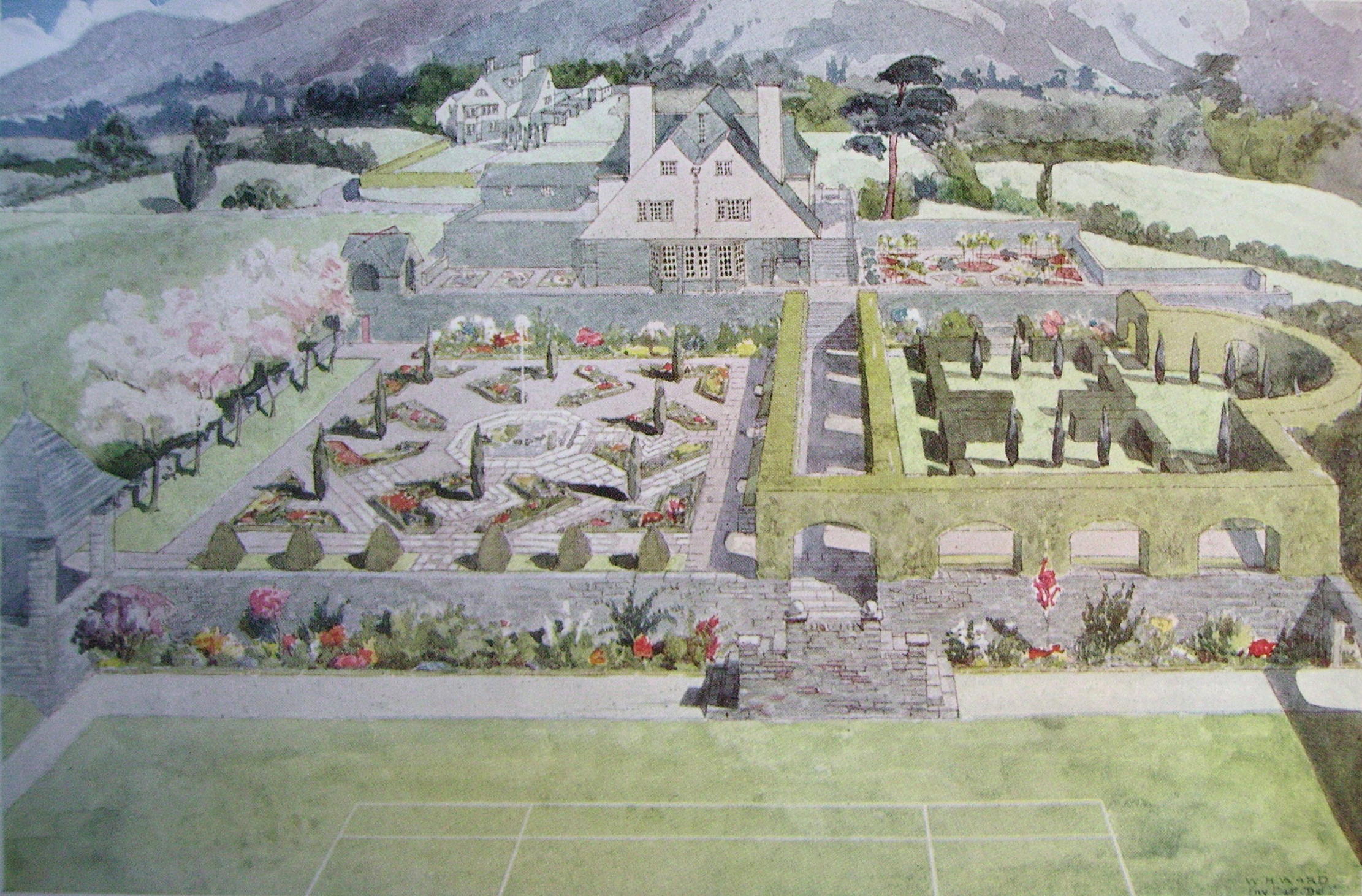

It seems certain that Ward and Mawson would have known each other. Indeed, a beautifully rendered — if fanciful — perspective drawing of the garden at High Moss, by Ward, was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1902 and reproduced by Mawson in the influential Studio Year-book of Decorative Art in 1908.

The drawing shows the handsome house, the terrace along its south façade and the path and run of steps through the garden set at right angles — but it ignores the steep slope that is key to its actual design. Ward went on to write what is still the definitive history of French Renaissance architecture: Mr Hughes is convinced that his love of French gardens and architecture influenced this delightful, but impossible scheme, which is so different to the satisfyingly integrated and practical garden that was in fact implemented.

Mr and Mrs Hughes have long felt there ought to be something to provide a focal point at the end of the path and Mr Hughes had in mind a cascade of water in the form of a diamond, a shape that recurs throughout High Moss. A talented craftsman in local Honister slate, Terry Hawkins, made the vision a reality, in time for the late Queen’s Platinum Jubilee and it was dedicated at the Village Party in the garden to celebrate the occasion.

Larch Cottage, Cumbria: An immersive journey amid a wealth of architecture, ornaments and plants to find magic and tranquillity

Charles Quest-Ritson joins the legion of garden enthusiasts who make the pilgrimage to the dramatic plant nurseries at Larch Cottage

Low Crag, Cumbria: A garden in perfect harmony within one of Britain's most beautiful places

The garden of Low Crag, Cumbria — home of Mr and Mrs Chris Dodd — demonstrates a thoughtful approach to

Lowther Castle: The spectacular and historic gardens that rise from one of Britain's most evocative ruins

The gardens at Lowther Castle, Penrith, Cumbria, rise artfully from the ruins of their spectacular setting — yet the effort

Credit: Jake Eastham

Rothay Manor — The Lake District as it should be: fresh air, breathtaking views, hearty food and a good night’s sleep

Octavia Pollock checks into Rothay Manor in Ambleside, Cumbria.

Warnell Hall, Cumbria: Where sympathy and experimentation go hand in hand

Non Morris is intrigued by the close attention to detail that has produced a new Cumbrian garden of great style

Credit: Hutton-in-the-Forest - Country Life / Val Corbett

Hutton-in-the-Forest's glorious gardens: From muddle to lightness and calm

The gardens at Everdon Hall: How an abandoned walled garden was turned into a secluded oasis of outdoor beauty

The gardens at Everdon Hall, Northamptonshire — the home of Charles and Caroline Coaker —show off a clean, green structure

-

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?The King's recent visit to Nansledan with the Prime Minister gives us a clue as to Labour's plans, but what are the benefits of traditional architecture? And can they solve a housing crisis?

By Lucy Denton

-

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breeds

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breedsPhotographer Melody Fisher has been travelling the UK taking photographs of ‘vulnerable’ spaniel breeds.

By Annunciata Elwes