The Duchess of Cornwall's gardens at Raymill, by Monty Don

Secreted in an idyllic spot by a charming mill leat, the 12-acre garden surrounding The Duchess of Cornwall’s treasured home is a precious refuge. Writer and broadcaster Monty Don takes a look, with photographs by Jason Ingram.

Royal Life is unimaginably attended. Life is plotted out in an unending procession of events, duties, attendances and performances, with every aspect prescribed by a retinue of the faithful, conscientious, anxious and frankly terrified. It must be completely exhausting for all concerned.

This is what makes Raymill — The Duchess of Cornwall’s private home and garden in Wiltshire for the past 25 years — doubly precious. ‘It is my refuge,’ she tells me. ‘The one place where I can be completely relaxed on my own terms.’ This forms the starting point for the whole garden.

It is big — there are 12 acres of tended grounds — but has an intimacy and idiosyncracy that can only come from a personal connection. Every area of the garden is part and parcel of a home, where lives are lived and shared, rather than a horticultural showpiece existing primarily for the admiring gaze.

The Duchess and Paul Jellyman, her head gardener for the past 13 years, take me on a tour, starting on the lawn behind the house. It is backed by an avenue of small-leaved limes, Tilia cordata, flanking what used to be the back drive. ‘I planted them too close together, of course,’ she admits. ‘Paul had to remove half of them — but when I was away, as I can’t bear to see trees come down.’ ‘It looks good now, Ma’am,’ Mr Jellyman adds. He is right. It looks great, the June leaves glossy and the spacing still not too far apart.

At the far end of the lawn, below a steep bank, is a large pond. Ducks navigate through the massed purple leaves of water lilies that, on the day of my visit in late May, are threatening to flower any day. ‘This was made by my predecessor as a trout hatchery,’ The Duchess explains. ‘It’s bonkers, really, but jolly nice to have such a big piece of water.’

On the far side, rhododendrons, azaleas and hydrangeas create a floral screen from spring through to autumn. The rhododendrons and azaleas come from the gardens at nearby Bowood House. Looking around, I can see beech, lime, lilacs and philadelphus in full flower — all indicators of an alkaline soil. However, Mr Jellyman points out that not only the plants, but the soil — lots of it — also came from Bowood, creating a suitably ericaceous ground for the plants to thrive in. A superb green acer, all layers of intricate green foliage, holds centre stage and willows rise from the water, some pollarded with fresh yellowy green shoots, another enormous, weeping down to the water’s surface.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A mulberry, growing on the lawn by the terrace, sprawls and leans in the louche way that mulberries inevitably will and alchemilla, forget-me-nots and erigeron emerge self-seeded from the gaps between the stones. In the border against the house, lupins, foxgloves, alliums and delphiniums are backed by Rosa‘Climbing Iceberg’ in full pomp, its pure-white flowers set against the foliage of a Banksia rose, only a hint of its small yellow flowers remaining. R. ‘Félicité-Perpétue’, with its small, pink-flushed white flowers and evergreen leaves, climbs around another corner of the house above an, as yet, small and brand new Duchess of Cornwall clematis.

There are roses everywhere, climbers, ramblers and shrubs, clambering up every available tree and wall and spilling exuberantly out from every border. Their uninhibited floral freedom sets the tone for the garden and reflects the influence of the American garden designer Lanning Roper, who had worked for both The Duchess’s parents and her grandmother, Sonia Cubitt. Roper was also recommended by The Duchess to help with the newly acquired Highgrove in the early 1980s, although his involvement in the latter was cut short by his early death in 1983.

To one side of the terrace, facing the lawn, is a vine house. Although it still holds a vine, the space is now dominated by white ‘Duke of York’ peaches planted two years ago that are already laden with small fruits — much to The Duchess’s pride and delight.

Wander through a glass door beyond the peachy vine house and you are in a courtyard containing a kidney-shaped swimming pool. As is the pond, this is a remnant from the previous owner, although the wisteria, ivy and more roses festooning the walls are very much The Duchess’s handiwork. This is a wholly private space, hidden from the rest of the garden, let alone the world beyond. Peonies line the bottom of the south-facing wall and the apricot blooms of the Duchess of Cornwall rose sit at the base of another. (‘Have you got me in your garden?’ The Duchess asks. I confess I have not, neither as rose nor clematis, but resolve to rectify the omission with celerity.)

The garden opens out beyond with a large kitchen garden at its heart. This is fully enclosed in chicken wire — the ceiling and walls protecting the harvest within from the predation of pigeons and, above all, squirrels. This is the domain of gardener Claire Quinney, who took an overgrown, slightly anarchic vegetable patch and marshalled it into the weed-free, productive exemplar that it is today. At its centre is a stone basin circled by comfrey and mint and a rose dome completely covered with ‘Rambling Rector’ and ‘Kiftsgate’ roses — the pruning of which, Mr Jellyman tells me, involves opening a hatch in the wire and balancing precariously on boards. ‘Slightly tricky — but we get it done,’ he says with a smile. Peas are ready for the first picking, the asparagus is in full flow, strawberries — given the double protection of dedicated mesh frames against any blackbirds that sneak in — ripen on clean straw and an entire catalogue of vegetables prosper in exemplary rows, together with cut flowers. It is a showpiece, but nothing is grown for show. If it can be eaten, it is — with relish.

The garden also contains several wide open spaces, each managed slightly differently. There is a meadow flanked by the mill leat from the River Avon, originating two years ago from green hay brought over from the wildflower meadow at Highgrove and spread out for the flower seeds to germinate, which is, indeed, happening. Beyond this meadow are The Duchess’s seven beehives, the honey from which, together with the honey from Highgrove, is sold by Fortnum & Mason to raise money for charity and has done so to the tune of more than £65,000 so far.

The largest area of open ground is the middle paddock. A family of elephants stands at its far end, partially hidden by copper beeches, both surreal and comfortably at home. These are a few of the 100 life-size and remarkably life-like sculptures, each one based on a real counterpart, made in Tamil Nadu from Lantana camara; the work has the happy effect of helping contain the invasive weed.

The elephants were due to be displayed in London for the charity CoExistence, set up by The Duchess’s late brother Mark Shand, but Covid meant they had to be housed elsewhere by volunteers who had the room.

As well as elephants, the middle paddock has fine trees. There are two good-sized oaks raised from acorns and a horse chestnut from a conker. An enormous weeping beech dominates one boundary, a long, immaculate beech hedge another. Indeeed, beeches of all kinds grow well here. A few of The Duchess’s favourite golden sycamores (Acer pseudoplatanus var. worleei), a tulip tree and a couple of walnuts make up the remainder, all planted in the past couple of decades. It is parkland with the sweep and scope of 18th-century landscaping and yet, despite the scale, is surprisingly intimate.

Wicker sheep and a cockerel graze in the undergrowth of the viburnum glade and, out of a large laurel, a painted tiger eyes them hungrily. ‘I have had him in every garden I have owned. He’s getting a little tatty, but recently had his eyes repainted,’ The Duchess explains, rather as one might refer to a much-loved pot that has had a chip repaired.

The orchard flanks one side of the drive. Beautifully pruned, mature, half-standard apples sit in a wide grid formation amid a tightly mown lawn. Their trunks are stark against the shining green of the grass and the splayed branches, blossom over, are heavy with foliage. It is very simple. That is the sum of it. But the repeated rhythm of the trunks, all alike, with some slightly at a cant, some splaying uneven, their neighbours rigidly true, is mesmerising.

I have known gardens created by the greatest designers and with astonishingly rare plants, all beautifully tended, that have been cold and unappealing. The best gardens are where Nature, humanity and personality come together, blended with a deep love of place and home — and Raymill has that in spades.

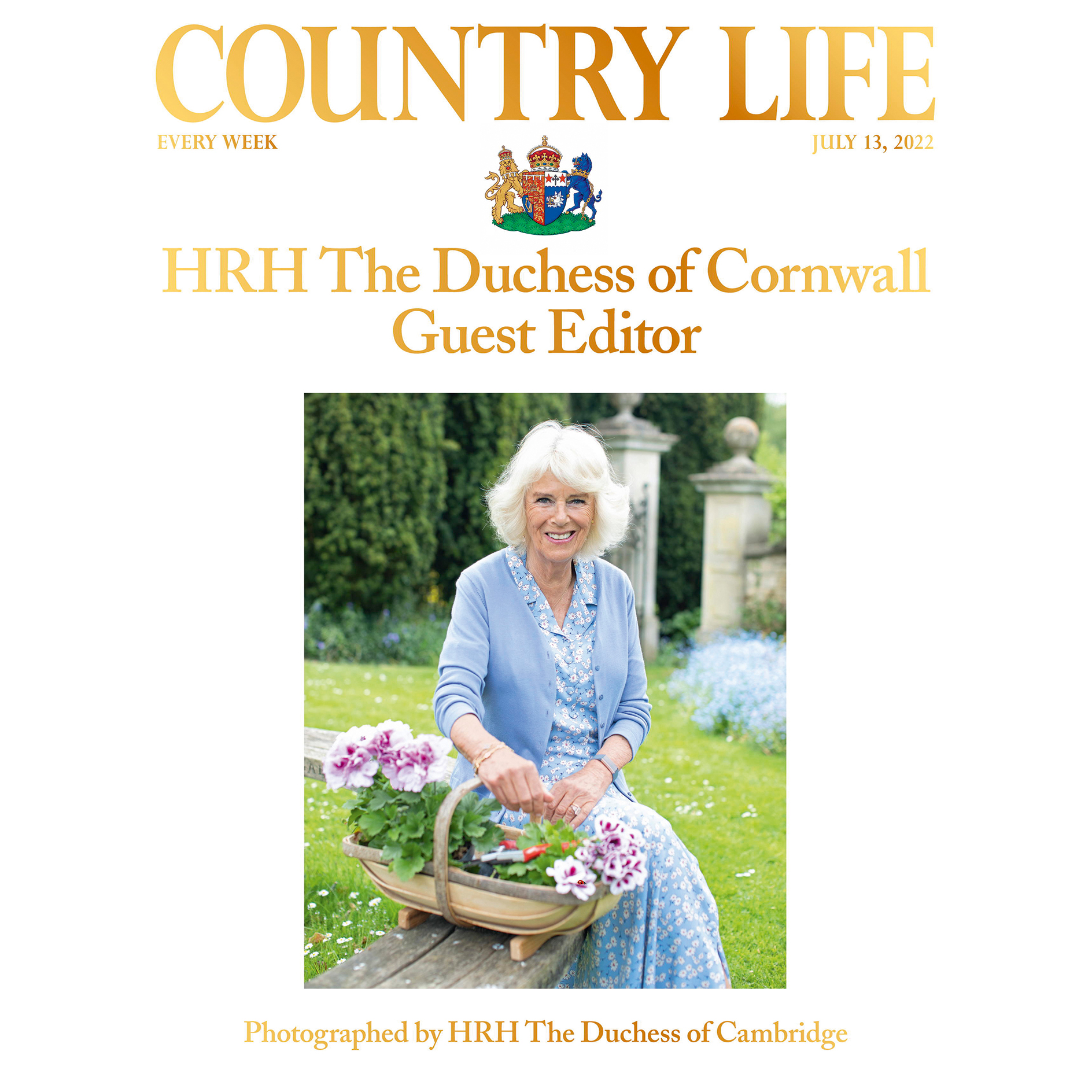

The Duchess of Cornwall, as photographed by The Duchess of Cambridge for Country Life

The upcoming 13 July 2022 issue of Country Life is being guest-edited by HRH The Duchess of Cornwall — and

The Duchess of Cornwall: ‘I have a profound sense of being at home in the countryside’

In her leader article in the 13th July 2022 issue of Country Life, guest editor HRH The Duchess of Cornwall

How to make The Duchess of Cornwall's favourite dish: Roast chicken with tarragon and cream

John Williams, the revered executive chef of The Ritz, cooks The Duchess of Cornwall's favourite dish: Roast chicken with tarragon

Video: The Duchess of Cornwall's guest-edit of Country Life, as featured on the BBC

Watch Paula Lester on BBC Breakfast discussing The Duchess of Cornwall's guest-edit of Country Life magazine, out on 13th July

Credit: Country Life

What's inside The Duchess of Cornwall's guest-edited issue of Country Life — and how to get your copy

We're thrilled and delighted that HRH Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, has guest edited the 13 July 2022 edition of Country

The behind-the-scenes story of The Duchess of Cornwall's guest-edit of Country Life

The 13 July 2022 edition of Country Life, guest-edited by HRH Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, has been a huge effort

The Duchess of Cornwall's country champions, from a bee master and an equine therapist to The Prince of Wales and Jeremy Clarkson

The Duchess of Cornwall names her countryside champions in the 13 July 2022 issue, which she has guest edited. Among

The Duchess of Cornwall's rescue dogs adorn a royal frontispiece like you've never seen before

This week’s frontispiece breaks from tradition — but they’re still ‘Girls in Pearls’.

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published

-

The man who trekked Bhutan, Mongolia, Japan, Tasmania and New Zealand to bring the world's greatest magnolias back to Kent

The man who trekked Bhutan, Mongolia, Japan, Tasmania and New Zealand to bring the world's greatest magnolias back to KentMagnolias don't get any more magnificent than the examples in the garden at White House Farm in Kent, home of Maurice Foster. Many of them were collected as seed in the wild — and they are only one aspect of his enthralling garden.

By Charles Quest-Ritson Published

-

The 'breathtakingly magnificent' English country gardens laid out on the Amalfi Coast, and the story of how they got there

The 'breathtakingly magnificent' English country gardens laid out on the Amalfi Coast, and the story of how they got thereKirsty Fergusson follows the Grand Tour to Campania in Italy, where the English combined their knowledge and love of plants with the rugged landscape to create gardens of extraordinary beauty.

By Kirsty Fergusson Published

-

Have your say in the Historic Houses Garden of the Year Awards 2025

Have your say in the Historic Houses Garden of the Year Awards 2025By Annunciata Elwes Published

-

Evenley Wood Garden: 'I didn't know a daffodil from a daisy! But being middle-aged, ignorant and obstinate, I persisted'

Evenley Wood Garden: 'I didn't know a daffodil from a daisy! But being middle-aged, ignorant and obstinate, I persisted'When Nicola Taylor took on her plantsman father’s flower-filled woodland, she knew more about horses than trees, but, as Tiffany Daneff discovers, that hasn’t stopped her from making a great success of the garden. Photographs by Clive Nichols.

By Tiffany Daneff Published

-

An expert guide to growing plants from seed

An expert guide to growing plants from seedAll you need to grow your own plants from seed is a pot, some compost, water and a sheltered place.

By John Hoyland Published

-

The best rhododendron and azalea gardens in Britain

The best rhododendron and azalea gardens in BritainIt's the time of year when rhododendrons, azaleas, magnolias and many more spring favourites are starting to light up the gardens of the nation. Here are the best places to go to enjoy them at their finest.

By Amie Elizabeth White Published

-

Great Comp: The blissful garden flooded with rhododendrons and azaleas that's just beyond the M25

Great Comp: The blissful garden flooded with rhododendrons and azaleas that's just beyond the M25Each spring, Great Comp Garden — just outside the M25, near Sevenoaks — erupts into bloom, with swathes of magnolias, azaleas and rhododendrons. Charles Quest-Ritson looks at what has become one of the finest gardens to visit in Kent.

By Charles Quest-Ritson Published

-

'I'm the expert who wrote the RHS's guide to roses — here's why pruning them right now is almost certainly a terrible mistake'

'I'm the expert who wrote the RHS's guide to roses — here's why pruning them right now is almost certainly a terrible mistake'More roses die from over-pruning than any other cause so what’s the reasoning underpinning this horticultural habit? Charles Quest-Ritson, the garden expert who wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses, takes a closer look.

By Charles Quest-Ritson Last updated