The Anderson shelter: Good for gardening, good for storing wine, and great for hiding from bombs

Damp, dimly lit and cramped they may have been, yet Anderson shelters were lifesavers during the Second World War. Russell Higham explores their legacy.

Anderson shelters, more than 3.5 million of which were dug into the back gardens of British homes during the Second World War as a last line of defence against the Luftwaffe’s deadly bombing raids, offer an exemplar of this country’s indomitable spirit of fortitude and pragmatism. Not only did they provide an economical, no-nonsense way for Britons to turn a ‘stiff upper lip’ to Hitler’s existential threat to everything we hold near and dear — they also, rather handily, afforded the opportunity for doing a nice spot of gardening at the same time.

Named after Sir John Anderson, the Lord Privy Seal in charge of air-raid precautions (ARP), these 6ft 6in long by 4ft 6in wide by 6ft high tubular shelters were made from curved sheets of corrugated iron, crudely bolted together to accommodate up to six people (four adults and two children). Commissioned in November 1938 in expectation of war and originally distributed to low-income households in areas likely to be targeted by German bombers — with the very first being installed in Islington, London, in February 1939 — they were later sold for £7 each (about £500 today). They enabled even the poorest families to cock a snook at Adolf by defiantly standing their ground at home, rather than being forced to scurry into overcrowded public shelters.

The self-assembly instructions dictated that the shelter should be half buried in the ground and covered with a layer of earth. This helped to reinforce the Anderson’s resistance to explosions, but also rendered them prone to flooding, especially in areas where the water table was high. It did, however, offer a silver lining that was well suited to the period of wartime austerity: it made them good for growing vegetables on.

‘Not carrots or potatoes,’ says Janice Munday, standing by the Anderson shelter to the rear of her home near Kennington Oval in south London. ‘The depth of the soil on top is only 12in at the maximum, so you can’t grow anything deep-rooted, but it’s good for herbs as it’s in the sun, as well as salad leaves, which are shallow-rooted.’

'We had two Ukrainian refugees living with us at the time and they were fascinated by our shelter,’ reflects Mr Stanley. ‘I think it must have seemed rather poignant to them'

She and her husband, Martin Stanley, who runs the highly informative website Anderson Shelters, acquired the mid-19th-century, four-storey house in Richborne Terrace, SW8, back in 1991. Discovering the shelter in their back garden — complete with the wire-mesh bunk beds that its wartime owners would have slept on during bombing raids — they were, at first, in two minds about whether to get rid of it.

‘We’re so glad we kept it, now,’ Mr Stanley reveals. ‘It’s a fascinating piece of Britain’s history and we open it up to school visits and for the London Open House Festival. Although anyone can come and have a look, free of charge, if they want to — as long as they arrange it in advance via the website.’

Unusually, this particular Anderson shelter is set into concrete, rather than earth: ‘The owner was a builder, so he knew how to make it even sturdier and more resilient to explosions. It also means we would have needed to hire a JCB to remove it, which would have been very expensive — so that’s one of the other reasons we decided to keep it. If we didn’t open it up to the public so often, we’d probably use it as a wine cellar, as many other people did with theirs, because it’s nice and cool down there.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

I can sense the temperature drop as I follow Mr Stanley down into the shelter’s narrow confines. ‘Because it’s sunk into the ground, it’s best to climb in backwards and descend the stairs as if boarding through the porthole of a submarine,’ he instructs. The analogy feels apt: it’s cosy bordering on claustrophobic and difficult to imagine how six people would have slept comfortably — especially with the risk of flooding, not to mention the threat of Nazi bombs. It’s easy to see why Morrison ‘table’ shelters — protective cages installed inside the home — which came along in 1941, proved a popular alternative.

During the harsh reality of life during the war, Andersons, whether loved or loathed, became enshrined in the public consciousness. The December 1940 issue of Good Housekeeping magazine contained a recipe for a Wartime Christmas Cake in the shape of the ubiquitous shelter, complete with marshmallow snow on top and described as a ‘topical cake for children’.

Mr Stanley knows of some 15 Anderson shelters left in the UK still intact in their original locations, with half of those being in the capital. Some have been sold or donated to museums (a reproduction of one is on display at the Imperial War Museum in London) and examples can change hands for anything from £100 up to £1,500.

Many shelters — excluding those that were reclaimed for their metal by the government after the war — were repurposed as potting sheds or pigsties. One in Lewisham in south-east London has become the centrepiece of a conservation project by volunteers working with underprivileged children and youths. At the same time as learning about their country’s heritage, they have helped to create a biodiverse home for wildlife and flowers, with the shelter itself now used as a den by a family of urban foxes.

Perhaps most encouraging of all is the benefit that Britain’s wartime legacy is having for current generations living in conflict zones. Two years ago, during the second phase of the Russia-Ukraine war, Mr Stanley and Miss Munday received a visitor to their Kennington home. A representative of Atlas Survival Shelters in Texas, US, came to study their Anderson shelter in order to build an updated version for Ukrainian families, to protect them from Russian shells and missiles. It’s now being produced in Poland.

‘We had two Ukrainian refugees living with us at the time and they were fascinated by our shelter,’ reflects Mr Stanley. ‘I think it must have seemed rather poignant to them.’

By the time the war ended in 1945, more than 50,000 people in Britain had lost their lives to Nazi bombing. Without Anderson shelters at the bottom of all those gardens, that number may well have been catastrophically higher. Damp, dimly lit and cramped they may have been, but they remained an invaluable refuge in the darkest of times.

Russell Higham is a freelance journalist and feature writer, with bylines in The Times, The Daily Telegraph and Country Life

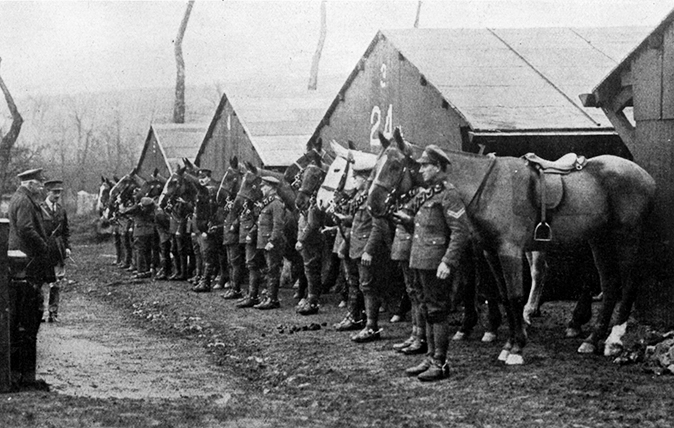

Country Life looks back at World War I

Country Life looks back at the First World War through the lens of the Country Life Archive. View images, read

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show stand

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show standInterior designer Isabella Worsley reveals her plans for Country Life’s ‘outdoor drawing room’ at this year’s RHS Chelsea Flower Show.

By Country Life

-

Schreiber House, 'the most significant London townhouse of the second half of the 20th century', is up for sale

Schreiber House, 'the most significant London townhouse of the second half of the 20th century', is up for saleThe five-bedroom Modernist masterpiece sits on the edge of Hampstead Heath.

By Lotte Brundle