Parasites of pleasure: the plants that live on plants and what to do with them

You might see it as an opportunity to grab a quick kiss at Christmas, but mistletoe is a parasite like any other, points out Charles Quest-Ritson.

Some of us are fated to desire plants that we will never grow. Sometimes, the problem is our climate — there is no point in longing to grow Amorphophallus titanum unless you can simulate its growing conditions in the jungles of Sumatra.

Another problem may be that the plants we long for are not available from British nurseries — I have been looking for stately herbaceous Eremostachys laciniata and the dwarf cherry Prunus incana ever since I saw them in Soviet Armenia nearly 50 years ago without success. However, the most intractable are those parasitic plants that live off other plants and take their entire nourishment from what their hosts can offer.

When we lived in Wiltshire — where we first opened our garden for the NGS in 1983 — I longed to grow mistletoe, which was entirely absent from our village in the lee of Salisbury Plain. I was told that it would grow on apple trees and, as we had inherited a fine orchard of nameless Victorian apple trees, I squeezed some of the black seeds out of the white berries and stuck them on parts of the branches where I thought they might arrive naturally. I waited, but nothing ever came of my labours and perhaps, on reflection, I should have anticipated that, if I had never seen mistletoe within at least 10 miles of our garden, my efforts were doomed to failure.

Years later, we bought a house in France and quickly learned that mistletoe was an invasive parasite that damaged Normandy’s cider apple trees. Wherever it sprouted, landowners were legally obliged to cut it off. I noticed, too, that mistletoe infected not only our cider apples, but ashes, hawthorns and (50ft up) our poplar trees, which were destined to make those boxes that Camembert is sold in. It dawned on me that mistletoe was so ubiquitous that all my neighbours had given up the struggle to control it.

Moreover, there were deserted orchards in the fields around us where the trees were so festooned with mistletoe that they were close to exhaustion. I therefore gave the legal requirements a Gallic shrug… until I began to find mistletoe establishing itself on apple trees that I had planted myself, whereupon I discovered that it is almost impossible to get out the roots (known as the haustorium) from under the bark.

Now, in the Itchen valley, every-one’s willows and poplars are loaded with mistletoe. Nevertheless, when I saw a Spanish species of mistletoe called Viscum cruciatum with red berries — almost as red as holly — in Andalucía last December, I longed to collect some seeds to try them out along-side their white cousins in Hampshire. However, I would have needed a phytosanitary certificate — Brexit spoils everything.

Among the many parasitic plants that I would like to grow are species of Orobanche or broomrapes — which have no chlorophyll, but take all their nourishment from their hosts. Some are serious pests of cultivated plants, but the ivy broom-rape — purple and cream — looks very pretty, as well as weakening the host ivy, which all gardeners recognise as a serious pest.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Then there’s the purple toothwort Lathraea clandestina, which grows on the roots of willows and poplars. I remember its spooky flowers along the Backs in Cambridge and the noisy pop when its seeds shoot out in search of new hosts. Better gardeners (or perhaps more fortunate) have succeeded in establishing it, but, so far, I have nothing to show for my efforts in Hampshire.

Best of all such parasites is the intensely scarlet Phelypaea tournefortii, which I have seen in the Caucasus and Pontic mountains. It should be growable in England because it attaches itself to members of the daisy family, such as tansy, but I have never heard of anyone succeeding. The flowers look as if they were painted by Hieronymus Bosch — but are spectacularly beautiful all the same.

Let us not forget Rafflesia arnoldii, the aptly named stinking corpse lily with the largest flowers in the entire plant kingdom. Those flowers may be 3ft in diameter, but it is nevertheless a complete parasite, taking all its nourishment from a tropical vine called Tetra-stigma. Imagine growing that in the Itchen valley and asking the neighbours round to have a sniff.

The year of the umbellifer: the glorious plant jesters thriving in the summer rain

Perhaps a bit prickly, these plants are loved by bumblebees and make a great splash of colour.

The case of the disappearing dahlias

John Hoyland of the gardens at Glyndebourne on how to plug the gaps of those flowers that didn't make it

Alan Titchmarsh: The best flower shows in Britain show exactly where RHS Chelsea gets it wrong

The Chelsea Flower Show might be the most famous in the world — but does it offer the best experience for

Credit: Clive Nichols

Charles Quest-Ritson: 'Gardens of supreme botanical importance are being degraded by new owners and changing priorities'

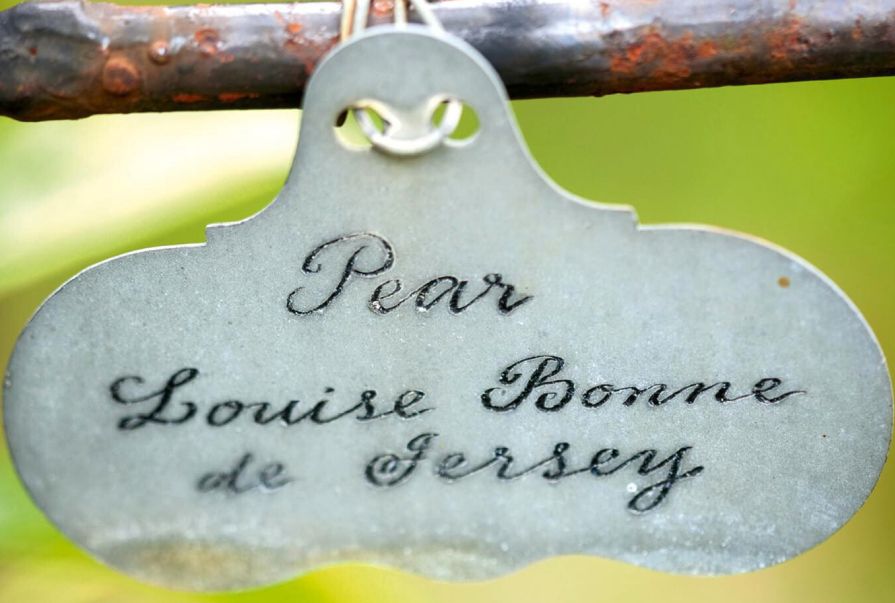

What's in a label? More than you might think, says Charles Quest-Ritson.

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-on-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.

-

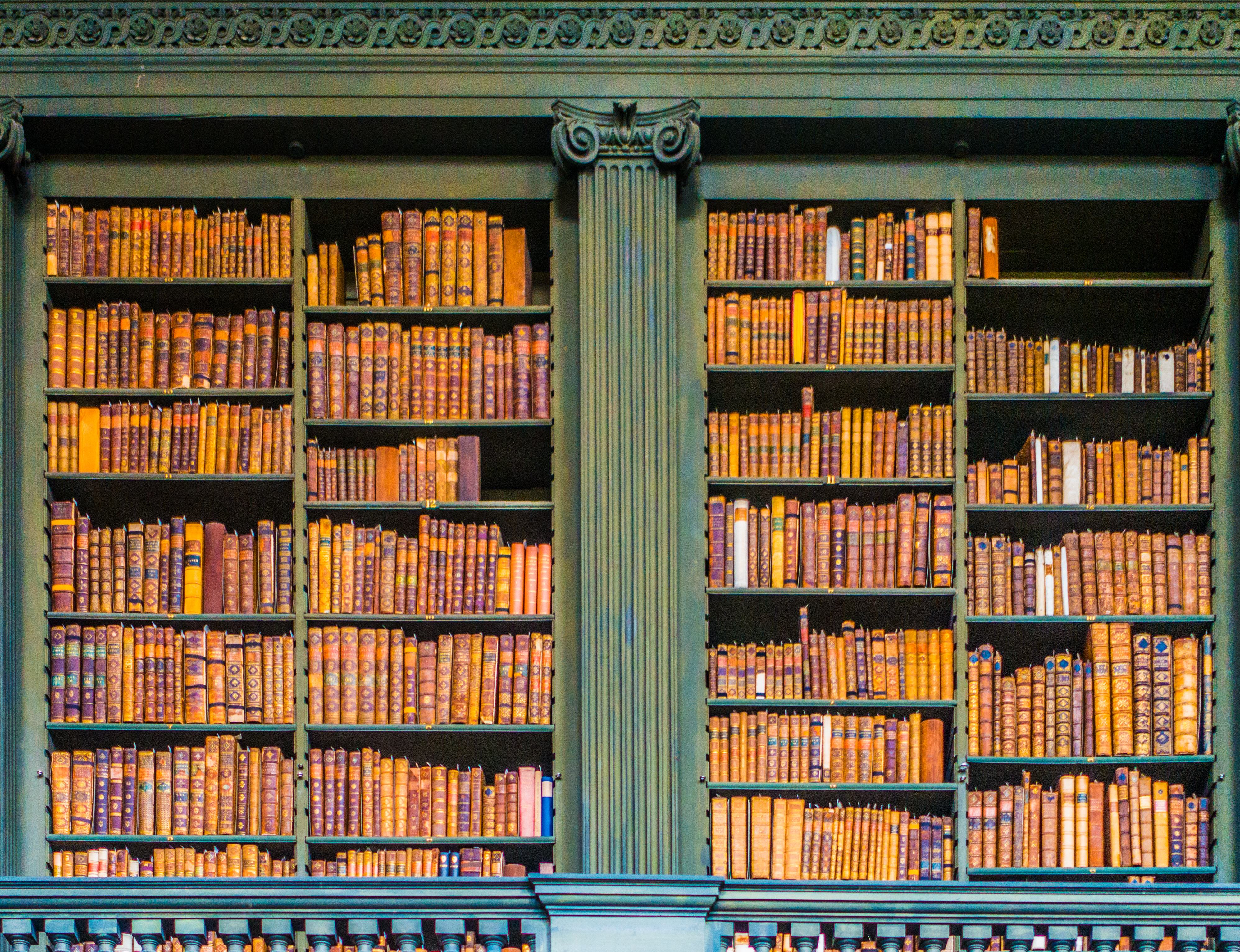

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life