Little Chapel: The tale of Guernsey's seashell-covered, miniature recreation of Lourdes

Designed as a miniature replica of the basilica at Lourdes, the seashell- and mosaic-decorated Little Chapel on Guernsey was at risk of collapse until a group of locals stepped in, as Arabella Youens discovers.

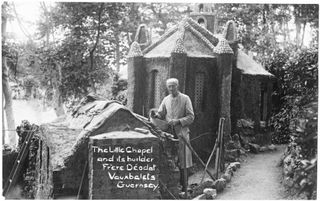

When the Roaring Twenties were in full throttle elsewhere in Europe, a member of the fraternity of De La Salle had his mind dedicated to other matters. The Brothers of the Christian Schools, a Catholic religious order, established themselves in Guernsey in 1904 and opened a Catholic boys’ school. One of the members, Brother Déodat, arrived to take up the role of sacristan on the eve of the First World War. Convinced that children learn mostly through their eyes, he had an idea. According to his diary, his attention was caught by a copse of trees in the Vauxbelets valley, which was — in his mind — eminently suitable for the erection of a grotto resembling that at Lourdes in France, with a miniature chapel to represent the Basilica of Massabielle.

It took three attempts to get the chapel right. The first, constructed in March 1914, was criticised by his fellow brothers for being too small and was torn down. A few months later, Brother Déodat established a grotto, which he adorned with a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes and later created a miniature chapel measuring 9ft by 6ft above. However, when the Catholic Bishop of Portsmouth visited in 1923, he couldn’t get through the door and refused to allow the chapel to be used for Holy Mass. This was taken as a sign by Déodat who set about demolishing the structure and he began a new, larger chapel measuring 16ft by 9ft — big enough to accommodate about eight people.

This time it would be decorated in a style called pique-assiette — literally meaning plate-pincher, the sort of person who might gatecrash a party to enjoy a free meal — with colourful pieces of broken china, pebbles and ormer shells. Used on a large scale, this technique has a mesmerising effect: Antoni Gaudí and Josep Maria Jujol’s Park Güell in Barcelona, Spain, is probably one of the most famous examples.

The process of applying the mosaic was long and arduous; Brother Déodat is said to have dedicated most of his free time for a period of several years to the task, which remained unfinished when he was forced to leave the island in 1939 due to ill health. Other brothers continued the endeavour and it didn’t take long for the project to amass dedicated followers.

An article in the Daily Mirror inspired many — including Wedgwood — to send coloured pieces of china to the island, others donated iridescent mother-of-pearl shells to further adorn the building. Small stained-glass windows were installed, which cast a rainbow of colour on floors that were fashioned out of pebbles. This beguiling spectacle has remained a site of pilgrimage, among both tourists and those with a more spiritual bent, on the island for decades; it’s one of the most visited attractions in Guernsey.

By 2016, the Little Chapel had, however, fallen into a state of disrepair: a huge crack had appeared in the floor and cavities had formed underneath. The original boys’ school, which had had the responsibility of upkeep, had closed down and another school, Blanchelande College, had taken over the site. ‘That school said it could no longer look after it and the brothers in France also couldn’t help,’ explains Nick Paluch, a local GP who looked after the monks, including the last Brother Director, and took on the role as secretary to the foundation established to look after the chapel. ‘It stands on a hillside and was built without foundations, so it is something of a miracle that it lasted for so long,’ says Dr Paluch.

Having launched an appeal to raise funds in 2016, the Little Chapel Foundation secured £500,000 from local donors and set about a programme of underpinning the building and carrying out some restoration to make it structurally safe. The works were completed in time to celebrate the chapel’s centenary earlier this year.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The project has involved a number of craftsmen and women based on the island, among them Andrea Guilbert. The Argentinian, whose husband, Alex, is from the island, has lived on Guernsey since 2005. ‘Our sons go to Blanchelande College and when I was visiting one day to say a prayer for a friend who was ill, I noticed that the face of the statue of Our Lady was stained as if something was leaking from the stone,’ she says. ‘I approached the foundation to see if I could help restore it and, to my surprise, they agreed.’

Having studied interior design in Buenos Aires, Mrs Guilbert, now a graphic designer, had worked with porcelain in the past. However, it wasn’t until she and her husband took the statue home that they realised it was made of cast iron; she had no experience in metal restoration. ‘The whole project was about 99% research and 1% perspiration,’ she explains, adding that she leaned on heritage metalwork conservationists across the UK for advice throughout the three-month project.

The restoration of the statue involved first using wire wool to remove the dust gently before a primer was applied. Next, it was painted all white, with a blue sash. The roses around the feet were given a warm red undercoat before they were gilded by transferring delicate sheet gold leaf and lightly brushing over the surface to give a soft shine.

That the work was undertaken without any prior experience is a fitting tribute; Brother Déodat himself was an autodidact. He improvised the building of the chapel and grotto by scavenging building materials such as clinkers — the stony residue from burnt coal produced by the island’s greenhouse industry — and offcuts of mortar and cement from various building sites.

Plans are now afoot to raise another round of funding for the Little Chapel to make the site more accessible, including erecting handrails to make it easier to walk around in wet weather and a disabled-access pathway from the car park.

‘The chapel is what people want it to be,’ says Dr Paluch. ‘I once described it as a work of art and a labour of love. It’s both these things and so much more. It’s the embodiment of one shy man’s deep devotion to Mary and a very personal, yet very public expression of his faith. Now that the De La Salle Brothers have left the island, we hope it will be a permanent reminder of their long association with the people of Guernsey and the selfless contribution they made not only to education, but also to the spiritual life of the island.’

Credit: Alamy

The story behind The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society is almost as fascinating as the book itself

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society has opened up the island’s charms to a new audience, finds Holly

-

How to disconnect from reality and feel like a new person in under 72 hours

How to disconnect from reality and feel like a new person in under 72 hoursOur round-up of the best British retreats that work wellness wonders in under 72 hours.

By Jennifer George Published

-

Evenley Wood Garden: 'I didn't know a daffodil from a daisy! But being middle-aged, ignorant and obstinate, I persisted'

Evenley Wood Garden: 'I didn't know a daffodil from a daisy! But being middle-aged, ignorant and obstinate, I persisted'When Nicola Taylor took on her plantsman father’s flower-filled woodland, she knew more about horses than trees, but, as Tiffany Daneff discovers, that hasn’t stopped her from making a great success of the garden. Photographs by Clive Nichols.

By Tiffany Daneff Published