Knowle Hill Farm, Kent: The hilltop garden to enjoy winter and early-spring flowers

A windy hilltop was no deterrent to the owners in creating a garden with a special focus on winter and early-spring flowers, finds George Plumptre.

It was when Elizabeth Cairns said casually ‘We’re very lucky, every year we have swifts nesting under the house roof eaves’ that I suddenly had a complete picture of her Kentish garden. Our most enigmatic and exciting aerial summer visitors, which spend the summer tearing and screaming through the sky in squadron-like flocks, have very specific nesting requirements and only frequent places that offer a particular, undisturbed welcome.

The swifts had long departed for their summer in Africa when I visited. Nonetheless, as I looked out from the garden’s spectacular vantage point across the wide expanse of the Weald, with low winter sunlight occasionally illuminating the scudding clouds, the garden’s peaceful friendliness was immediately evident.

Positioned just below the narrow greensand ridge that runs from east to west through Kent, between the chalk North Downs to the north and the expanse of the Weald to the south, the view was a decisive factor when Elizabeth and her husband, Andrew, purchased Knowle Hill in 1982. There was no garden to speak of and, when faced with decrepit farm buildings, it was reassuring to have the incentive of creating a garden to make the most of the position and outlook.

Their canvas was made even blanker a few years later, when the 1987 storm removed the few trees they had inherited. Starting a garden from scratch can be daunting, but Elizabeth was wisely patient, slowly developing the two acres that surround the house both to bring out the character in different areas created by the undulating terrain and to make it more accessible and integrated with flights of steps.

One subtle benefit of gradual progress over many years has been that the garden’s footprint is reassuringly light. As a result, the informal pattern of lawns and borders, the lines of which are accentuated by hedges, domes and topiary birds of clipped box and yew, and the steps and paths that link them, has been gently integrated into the landscape of the site rather than bringing about wholesale change to its character and terrain.

The most overtly architectural addition has been a broad York-stone terrace along the front of the house. Given that the ground drops inexorably away from the house, the terrace provides a secure platform from which to look out at the view across a wide lawn sloping away to the garden’s boundary of undulating box hedges and the panorama of countryside beyond. Clipped domes of lavender are a feature all along the terrace and a variety of salvias are particularly good among the mixed summer planting.

Shortly after their arrival at Knowle Hill, the Cairnses discovered a few scattered clumps of snowdrops, but it was the gift of a miscellaneous group of different snowdrops from Elizabeth’s university friend, the distinguished plantsman and botanist Martyn Rix, that first aroused the specialist interest that now gives her garden a very distinctive quality through late winter and early spring. She was intrigued by the pronounced differences in the snowdrop family and, over the years, has integrated a wide range throughout the garden.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There was also a quite different inspiration for one of her most successful snowdrop plantings. Knowle Hill’s position might provide enviable views, but it also made the garden cruelly exposed to prevailing winter winds. They decided to put in a protective windbreak of trees along their western boundary, planting it with native English species, in particular quantities of hazel. Beneath and around the coppiced clumps Elizabeth introduced the common snowdrop, Galanthus nivalis, which will naturalise more reliably than any other variety.

However, she confirms wryly: ‘Naturalising snowdrops is a steady process and needs to be helped along by annual splitting and replanting of clumps in the spring.’ Today, solid drifts of both single and double snowdrops make a white carpet all through the little wood, mixing in places with delicate pink-and-white Cyclamen coum and bright-yellow aconites.

Many of the more unusual species of snowdrops do not readily naturalise and so Elizabeth has mixed them up throughout the different beds and borders in the garden. Overall, she likes those with a distinctive habit and has a few particular favourites. Very sensibly, she says that she prefers ‘the good doers’, but goes on to admit that ‘one or two of the frailer and more fussy ones are too delectable to miss out’.

She is intrigued by Three Ships, a rare treasure that always flowers at Knowle Hill by December 1. Mrs Macnamara is usually in flower for Christmas and Galatea is an old variety that also flowers early. A particular attraction of snowdrops is the very personal connotations of their names, not least Angelique, which has tiny green dots on the inner segments and was named after a French girl whose life was cut tragically short.

Many of Elizabeth’s favourites have distinctive markings, such as Robin Hood, which is shaded with an X shape, and Cicely Hall – another one that needs cosseting – with dark green on the inner segments.

She admires Fly Fishing – ‘so elegant and refined, with its extra long pedicels sup- posedly like a fly fishing rod’ – and Wendy’s Gold is one of the few snowdrops with yellow markings that she favours, because it’s such a good plant and showy.

Today, visitors can enjoy some 90 named varieties of snowdrops as well as large groups that are forms of Galanthuses nivalis, plicatus and elwesii. Elizabeth’s enthusiasm is evident, but her skill has been to grow her snowdrops as garden plants, not as a trainspotter-style collection and she’s philosophical about the balance of success and failure. ‘Every year, we acquire a few special ones; some have clumped up well, but others have disappeared without trace.’

Towards the top of the garden, two borders are given symmetry by domes of box clipped neatly into buns. The borders direct views to a sculpture made by the Cairnses’ son, Bertie, which is set off by curving yew hedges and, as one moves through the garden, the contribution of structural clipped hedges and topiary becomes increasingly evident. It seems to continue the heritage of the old boundary box hedges inherited to the front of the house, which are now clipped into billowing cloud shapes.

Elsewhere, an arched opening in another yew hedge leads to the small wildflower meadow, which has been developed in recent years after an initial battle to eradicate all the dormant weeds that sprang up at the first sign of cultivation. Now, there is a succession from early spring of crocus to small narcissus, then cowslips, which are particularly good.

As I leave Knowle Hill, my last view is of the beautifully crafted iron weather-vane on the barn roof, which incorporates a trio of swifts. I decide I would like to return to the garden on a summer evening when the birds have arrived to nest and are racing noisily around the farmhouse, when delicate Queen Anne’s lace might still be out in the meadow and Elizabeth’s summer favourites – such as the China rose, Comtesse du Cayla – are in flower.

The garden of Knowle Hill Farm, Maidstone, Kent, is open in aid of the NGS on February 3 and 4 and July 15 (www.ngs.org.uk) and on other days by prior arrangement (elizabeth@knowlehillfarm.co.uk).

Ablington Manor: A magnificent house and gardens almost untouched by the passing of time

Ablington Manor: A magnificent house and gardens almost untouched by the passing of time

The snowdrops of Oxford: How the city fell in love with winter's most entrancing flowers

The city of Oxford has long been a destination for snowdrop enthusiasts and one of the university’s colleges displays its

Credit: ALAMY

10 pictures of the world’s largest yew hedge which are almost beyond belief

The world’s tallest yew hedge, on the Bathurst estate in the Cotswolds, has just received its annual trim.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

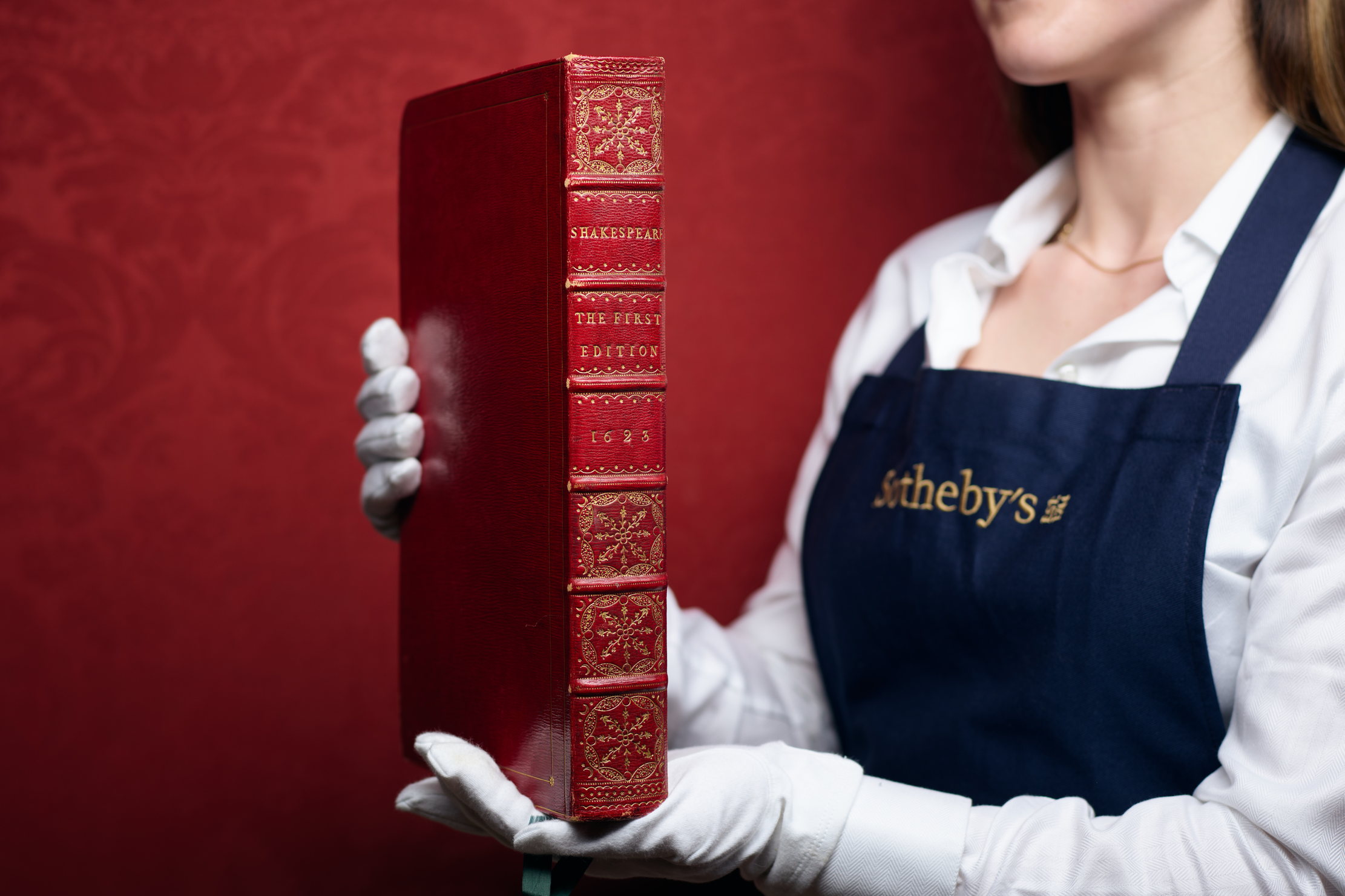

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher

-

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needs

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needsClematis montana is easy to grow and look after, and is considered by some to be 'the most graceful and floriferous of all'.

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

The man who trekked Bhutan, Mongolia, Japan, Tasmania and New Zealand to bring the world's greatest magnolias back to Kent

The man who trekked Bhutan, Mongolia, Japan, Tasmania and New Zealand to bring the world's greatest magnolias back to KentMagnolias don't get any more magnificent than the examples in the garden at White House Farm in Kent, home of Maurice Foster. Many of them were collected as seed in the wild — and they are only one aspect of his enthralling garden.

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

The 'breathtakingly magnificent' English country gardens laid out on the Amalfi Coast, and the story of how they got there

The 'breathtakingly magnificent' English country gardens laid out on the Amalfi Coast, and the story of how they got thereKirsty Fergusson follows the Grand Tour to Campania in Italy, where the English combined their knowledge and love of plants with the rugged landscape to create gardens of extraordinary beauty.

By Kirsty Fergusson

-

Have your say in the Historic Houses Garden of the Year Awards 2025

Have your say in the Historic Houses Garden of the Year Awards 2025By Annunciata Elwes

-

Evenley Wood Garden: 'I didn't know a daffodil from a daisy! But being middle-aged, ignorant and obstinate, I persisted'

Evenley Wood Garden: 'I didn't know a daffodil from a daisy! But being middle-aged, ignorant and obstinate, I persisted'When Nicola Taylor took on her plantsman father’s flower-filled woodland, she knew more about horses than trees, but, as Tiffany Daneff discovers, that hasn’t stopped her from making a great success of the garden. Photographs by Clive Nichols.

By Tiffany Daneff

-

An expert guide to growing plants from seed

An expert guide to growing plants from seedAll you need to grow your own plants from seed is a pot, some compost, water and a sheltered place.

By John Hoyland

-

The best rhododendron and azalea gardens in Britain

The best rhododendron and azalea gardens in BritainIt's the time of year when rhododendrons, azaleas, magnolias and many more spring favourites are starting to light up the gardens of the nation. Here are the best places to go to enjoy them at their finest.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

Great Comp: The blissful garden flooded with rhododendrons and azaleas that's just beyond the M25

Great Comp: The blissful garden flooded with rhododendrons and azaleas that's just beyond the M25Each spring, Great Comp Garden — just outside the M25, near Sevenoaks — erupts into bloom, with swathes of magnolias, azaleas and rhododendrons. Charles Quest-Ritson looks at what has become one of the finest gardens to visit in Kent.

By Charles Quest-Ritson