The most impressive perennial grown in Britain: The swamp pot

Mark Griffiths extols the wonders of the swamp pot ‘Thalia dealbata’ and teaches us how to best do the beautiful flowers justice.

On the small terrace where I sit between bouts of gardening and writing, I’ve been delighting in the company of Thalia dealbata. From July until summer’s end, it is by far the most impressive perennial we grow. Large-bladed, long-shafted and gunmetal grey, its leaves stand in clumps, resembling raised oars. Over them, flowers hover, crystallised violets that dangle in tresses from wand-like stalks up to 6ft tall.

It hails from rivers and swamps in the American Deep South. There, it’s known as powdery alligator flag or hardy canna, although it’s neither a flag (water iris) nor a Canna. It is powdery, however, as if dredged with icing sugar, hence dealbata, ‘whitened’.

As for the name Thalia, in this case and unlike Narcissus Thalia, it does not belong to the muse of comedy and bucolic poetry; rather, it honours Johannes Thal, a 16th-century German physician and botanist.

This magnificent aquatic has captivated botanists as well as gardeners. It belongs to the family Marantaceae, together with the popular houseplant Maranta leuconeura. The latter is known as the prayer plant, because its leaves fold upwards and together at night. Thalia dealbata also exhibits sleep movements, only its foliage folds downwards, a phenomenon examined by Charles Darwin, who grew it at Down House.

Lately, scientists have been studying Thalia’s explosive (but harmless) pollen release, a trick it performs in less than 0.03 of a second. For all its stately serenity, Thalia is one of the world’s fastest organisms.

'It’s too special for a pond, too outlandishly incongruous'

It will grow in an outdoor pond, planted in the margins or plunged in a waterlily basket with its crown no more than 1ft below the surface, but it seldom flourishes, needing warmer water when in growth than most pools afford. Frankly, it seems too special for a garden pond and too outlandishly incongruous. Instead, I grow Thalia dealbata in a sun-soaked sheltered spot (my terrace) in a large, free-standing bowl all of its own – a ‘swamp pot’ as a friend from Louisiana (aptly enough) once described such containers to me.

Over the years, I’ve made swamp pots of quite a miscellany of receptacles – oak half-barrels, glazed earthenware bowls and jars from the Far East, lead tanks, stone urns, cache-pots and proper plant pots, too, with the drainage holes plugged and the base of their interiors coated with aquarium sealant.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

We fill them half to two-thirds deep with a loamy, mildly acidic soil that’s rich in compost and laced with that grisly-sounding, but unbeatable old staple blood, fish and bone (swamp pots benefit from fertiliser, unlike ponds).

Thus prepared, the pots are ready for planting, positioning and filling to the brim with water. Once the plants are growing lustily, we give them a fortnightly dilute liquid feed. By replenishing the water until it’s fast overflowing, we dispel any miasmic vapours and dash mosquito larvae to their doom.

To remove another potential nuisance, algae, we insert a stick and twirl gently, gathering the slime on its end as if it were some hideously healthy candy-floss substitute.

Like Thalia dealbata, tender and semi-hardy aquatics tend to look and fare better when planted in swamp pots and sited in hotspots than when they’re plunged in outdoor ponds for the summer. They include the sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera), Egyptian papyrus (Cyperus papyrus, especially the compact cultivars Nanus and Perka-mentus), ornamental selections of taro (Colocasia esculenta, notably, Black Magic, with massive arrowhead leaves in satiny aubergine-purple) and water cannas (such as Canna Erebus with blue-grey leaves and peachy pink butterfly blooms).

As winter approaches, we tip the standing water out of the containers of these cold-shy exotics and move them to frost-free quarters, leaving them to slumber in wet soil until spring’s heat stirs them into demanding fresh food and drink.

If that sounds like too much fuss and heavy lifting, one can always use hardy aquatics in swamp pots that are left in situ all year round, especially plants that are too striking to suit the gentle naturalism that becomes English garden ponds. For example, grown in a blue-glazed bowl, the yellow-striped reed, Phragmites australis Variegatus, is pure poetry in planting.

Filled with the horsetail Equisetum hyemale, rectilinear containers in zinc or stone are microcosms of minimalist chic. Best of all is my Southern belle Thalia dealbata. Come December, I’ll have to cut her back and cover her with a sack, but that’s a long way off and only after a summer of liaisons on the terrace with this explosive, but exquisite naiad.

How to restore and update a period kitchen garden

If you have a kitchen garden in your period property it can be easily adapted for modern living by being

Sussex country house with woodland and bluebells

A pretty country house with eight acres of land and spacious accommodation dates back to the 16th century

Climbing Ben Stack: A perfect, conical mountain whose paths are adorned with bluebells, violets and orchids

Fiona Reynolds takes time out during a trip to Scotland to climb one of its most beautiful little peaks: Ben

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

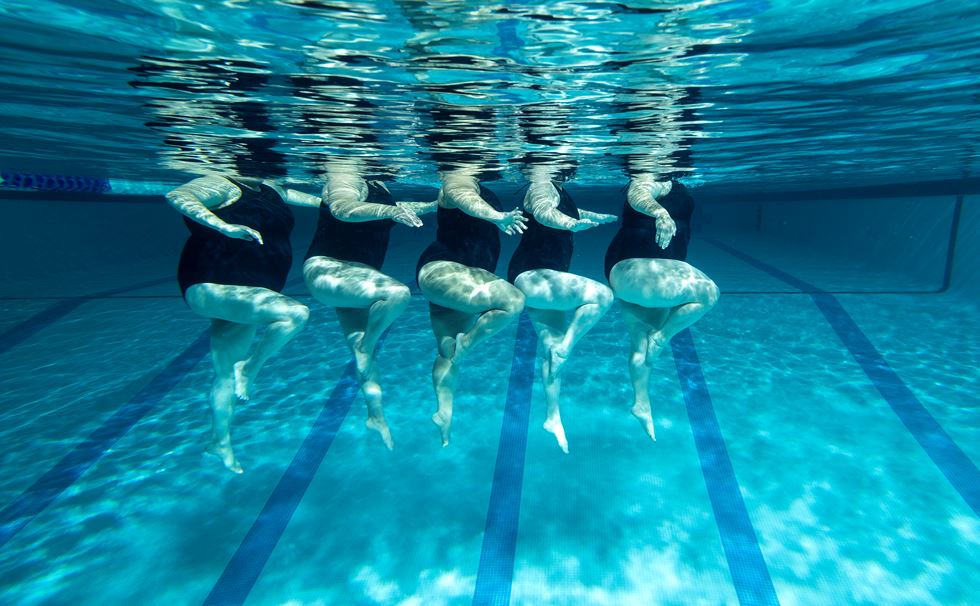

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes