'I followed a lorry for miles just so I could ask the driver if I could buy his pot': How Beth Tarling put together her dream terracotta pot collection

Ordinary terracotta flowerpots have been made in their millions and yet, as collector Beth Tarling tells Tiffany Daneff, there is very little on record about them. Photographs by Mark Bolton.

‘There is one field between us and the sea,’ says Beth Tarling. She lives in Gunwalloe on the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, where, for the past 10 years, she has been building a collection of vintage flowerpots. Not early Dutch porcelain or French lead planters, but ordinary, everyday terracotta flowerpots.

Plenty of gardeners prefer their weathered surfaces: collections of geraniums and auriculas look so much nicer in old pots than in the brash orange of a new one. Finding the occasional old pot is one thing, but Mrs Tarling has achieved the rare feat of assembling a complete set of every size of pot that was handthrown by Richard Sankey & Son, of Bulwell in Nottinghamshire, as well as many other rarities, including a fragile, possibly 18th-century, flowerpot. Sankey, founded in the 1850s and Royal Warrant holders, were the largest producers of handthrown clay pots in the world.

A post shared by Coastal cottage garden (@seaview_gunwalloe)

A photo posted by on

Mrs Tarling, who had worked for Laura Ashley since she was 18 years old, had always liked old flowerpots, but became serious about collecting them after watching a video of The Victorian Kitchen Garden, which aired on BBC2 in 1987. ‘I first watched the series with my grandmother and then my mum,’ she recalls. ‘About 10 years ago, I was given the DVD as a present. I was fascinated by the bit where the presenter Peter Thoday talked about pots.’

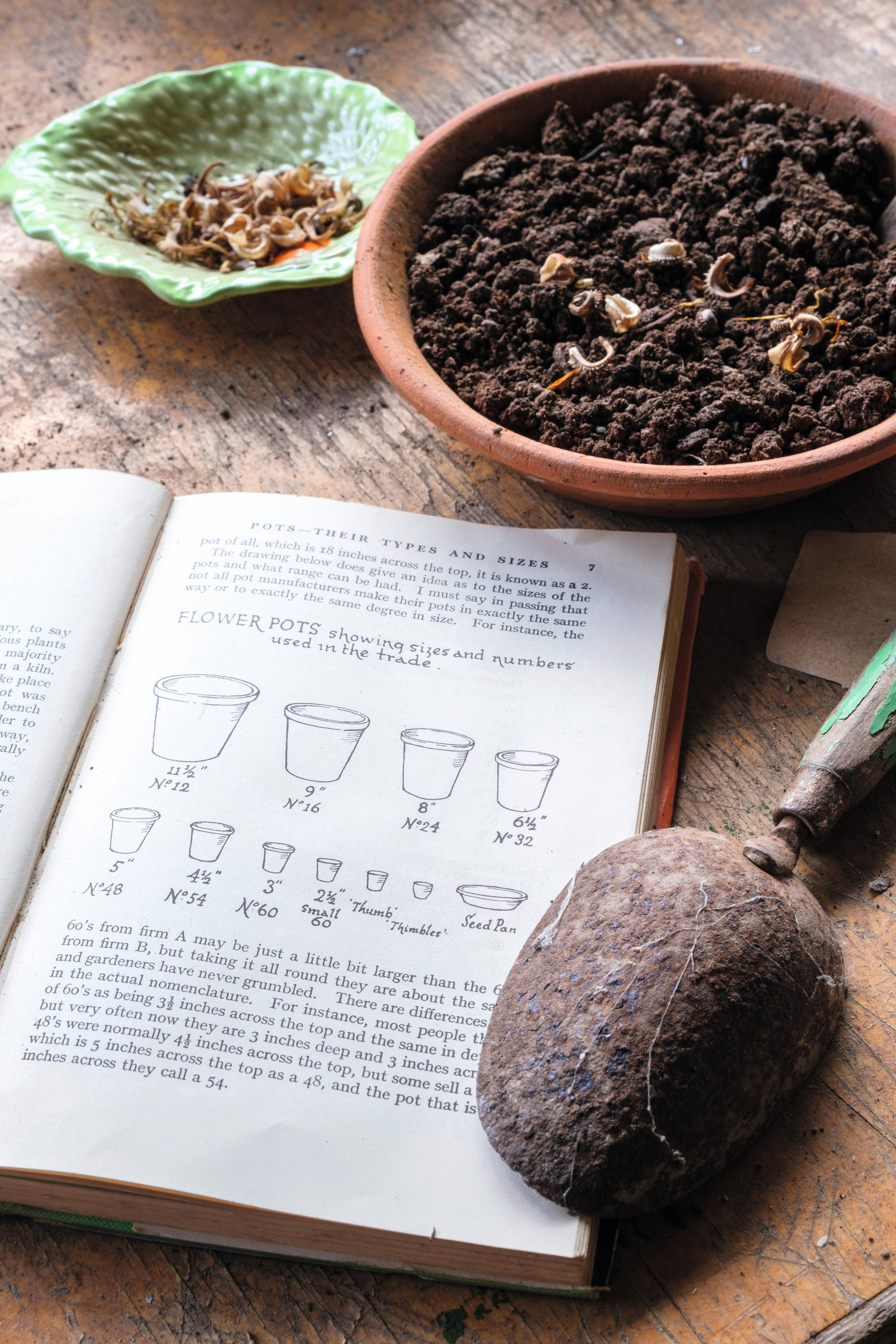

Thoday, who died in 2023, was a horticultural lecturer and was involved in the restoration of Cornwall’s Lost Gardens of Heligan. In the programme, he explained how flowerpots were originally numbered according to how many pots of that size were produced from the original lump of clay the potter was working with. A No 60 pot meant that 60 of that size were made from one unit of clay, whereas the biggest size, the No 1, was thrown using the entire lump or ‘cast’. The cast was the unit of pay based on the weight of the clay. Smallest of all were the thumb (for tomato seedlings) and thimble pots (for starting cauliflower), which weren’t numbered. Above 54, the pots had rims.

W. E. Shewell-Cooper’s A.B.C. of Gardening (1958) shows how pots were sized.

When pots began to be machine-pressed, the system of identifying them changed, reflecting, instead, the interior diameter at the top of each pot — the system we still use today for all flowerpots, whether clay or plastic. ‘A skilled thrower,’ says Jim Keeling of Whichford Pottery, Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire, ‘would make 20 cast a day.’

‘Although we have 500 gardening books here, none contained that information,’ reveals Mrs Tarling. She contacted Thoday, who confirmed that there was very little information about ordinary flowerpots. ‘They were such everyday objects that nobody thought to record anything about them,’ Mrs Tarling points out. It didn’t help that a devastating fire at the Bulwell factory in 1980 had destroyed everything, including all the Sankey records. Nor were matters simplified by the fact that, in the early days, there were many potteries sizing their pots slightly differently. To complicate matters even further, most pots had no mark or name on them. ‘For every pot we have with a mark, we have 50 unmarked ones,’ says Mrs Tarling.

Jim Keeling was astounded to discover, when researching his first book The Terracotta Gardener (1990) that the V&A Museum in London, which was partly set up to recognise the manufacturing and folk arts, did not contain a single flowerpot. ‘The country ware is there, but not the flowerpots, which is extraordinary when you think of all those millions that were made. The orders from growers would have been in the hundreds of thousands.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Flowerpots from a variety of English potteries, including G. A. Tuck of Waltham Abbey, Essex, who took over the factory founded in 1831 by H. F. Walker.

Undeterred, Mrs Tarling started putting all her old pots in order of size. The next step was to track down the missing ones, with Dan Tarling driving his wife to many auctions and garden sales. Her father even crossed Hampshire to collect a load of bulb pans.

There had been itinerant potters for years, but evidence of large-scale potteries situated near clay pits was recorded around the country in the early 18th century. Variation in the clay produced slightly different coloured pots. ‘Somerset pots are very pale, almost biscuity,’ says Mrs Tarling, ‘whereas those from Manchester are nearly chocolate in hue.’

According to a paper by C. K. Currie (The Archaeology of the Flowerpot in England and Wales c 1650–1950, published in the journal Garden History, 1993), the flowerpot ‘is by far the most common item found during archaeological work on late post-medieval gardens, but is almost entirely absent from discussion in archaeological literature’. Currie suggests that the explosion of interest in new plants and plant collecting that developed in the late 18th century meant that pots would have been essential for transport. ‘When HMS Bounty sailed to collect specimens of breadfruit from the South Seas in 1787, provision was made for 1,015 seedlings to be kept in racked pots.’

In 1810, Richard Sankey’s father opened a pottery in Nuneaton. By the middle of the same century, horticulture was becoming increasingly popular, with new plant nurseries supplying the growing middle classes who were beginning to spend on their gardens, houseplants and glasshouses (which became cheaper to install after the abolition of the window tax in 1851). Seeing how the wind was blowing, Sankey opened a second pottery in Bulwell. By 1912, Bulwell was reported to be producing 500,000 pots a week (as Maurice Baren noted in How It All Began in the Garden). Some 12½ tons of coal were required to fire a kiln for 72 hours and Sankey had its own railway siding to load up the finished pieces, some going as far as New Zealand, Jamaica and British Columbia. After the Second World War, Sankey introduced mechanisation and, in 1976, the factory ceased clay production.

A rare photograph of pot boys at Richard Sankey & Son in Bulwell, Nottingham, once the largest supplier of flowerpots in the world.

How can one tell the vintage of a weathered terracotta flowerpot? ‘The feel of the clay,’ says Mrs Tarling. ‘When you touch a machine-pressed one, it feels straight and smooth to the touch. The handthrown ones feel more granular.’ Often, the potter’s thumb marks are visible on the inside of a thrown pot.

Her favourite flowerpot? One made in Somerset. ‘It came off the back of a lorry that was heading to the dump. I could see it was badly broken, but it had a splendid old mend. I followed it for a good couple of miles and, when the driver finally stopped at a shop, I asked if I could buy it. I wouldn’t part with it for anything.’

The hardest to find was the huge No 1 Sankey. Her friends Piers Newth and Louise Allen of Garden & Wood in Biddestone, Wiltshire, are specialists in antique garden supplies and spent about five years searching. ‘I thought my legs were going to give way when they finally brought me the No 1.’

It took 10 years for Beth Tarling to collect the set of Sankey pots. No 1 weighs half a hundredweight.

The pot collections and rare finds at Garden Cottage are kept undercover in a shed specially built by Mr Tarling and are always popular with visitors. The rest of the vintage pots are in use. They are filled with strawberries and annuals. ‘I like them in groups of six or 12 because they were originally sold in dozens.’

Seed sowing and pricking out are always done in terracotta pans, never plastic. ‘I cannot understand the popularity of plastic when so much terracotta has survived. Planting in pots that have been treasured for generations gives so much pleasure. If you make tea, you wouldn’t drink it out of a plastic cup you throw away afterwards.’

Garden Cottage, Gunwalloe, Helston, Cornwall, opens by prior arrangement for the National Garden Scheme — find out more here. £5 per person, and cream teas are available.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher Published

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon Published