Rage against the buttercups: How to wage war on the weeds in your garden

Charles Quest-Ritson loves plants — but in his garden, he only wants the ones he chooses.

Weeds are fashionable. Everyone, we are told, has a favourite weed and tolerates its presence in the garden. Buttercups — one of the most pernicious weeds — were a common component of several prize-winning gardens at Chelsea last year. Horticultural chatterers are united in their approval: how bold, how charming, how sophisticated.

Well, I loathe weeds. They compete with the plants that I want to grow. They’re all very well in verges, meadows and woodlands, but those are the places where they truly belong. A garden is an artificial creation, and weeds have no place in it.

I like to see my peonies and roses set off by the soft colours and the pleasing forms of violas, astrantias and herbaceous geraniums. Nothing annoys me more than a cocky yellow buttercup getting in the way. Yes, I could transplant it to my yellow garden, together with cheerful dandelions and poisonous ragwort. But weeds are weeds and it’s no use pretending that they are essential elements of any horticultural composition.

At least, not mine.

One reason for this new-fangled fashion is the ill-founded belief that weeding out couch-grass, ground elder and cow parsley is an endless, disagreeable chore. Endless perhaps, but by no means disagreeable.

Weeding is a most satisfying pastime. Relaxing, too. It gives you the opportunity to think, to ponder, to let your mind settle the problems of everyday life. Some people say the same about housework, and add that there’s no substantive difference between cleaning the house and cleaning the garden. I accept that both activities are statements of civilised behaviour, but I do not derive the same calming effect from dusting and polishing.

"It all comes back to what we hope to achieve by gardening. I see no point in tolerating native plants that will overrun the prettier ones that I wish to cultivate."

Weeds will always be with us. New ones emerge every day. Happy the gardener, they say, who cleans up all his beds and borders by the end of March, which is what the pundits encourage us to do. Yet even that offers no protection against the new weeds that will germinate once the soil warms up.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Early weeds are not so much of a problem. Under no circumstances, however, should a gardener take a holiday in May — it is the month in which weeds of every sort put on a spurt of exponential growth. Go away for a week and you will never catch up again.

One of the troubles is that goody-goody legislators have deprived us of all the best means of defence. Simazine, now no longer available to amateur gardeners, was essential to the success of my first garden. It is a pre-emergence weedkiller — in other words, it clobbers seeds as soon as they try to germinate. Inevitably, over the years, plant forms have evolved that are resistant to its toxic effect.

Viola was one of the first genera to conquer Simazine and delighted me when seedlings of violets and pansies — but nothing else — popped up all around my roses. I think of the stuff ruefully every year when millions of tiny willowherb seedlings invade my beds and borders because I have nothing with which to deter them.

We won’t have glyphosate for much longer either. The Luddites and killjoys will soon deprive us of one of the most useful of herbicides — one that has done inestimable good in increasing our food crops and clearing clogged waterways.

Actually, I prefer Basta, a contact weedkiller that you spray on herbaceous plants — they simply shrivel up and die. Potato-growers use it to dry out the haulm before sending in their tractors to harvest the crop. It’s safer with plants such as roses, because Roundup twists and distorts the growth of any rose it touches. Yet Basta, too, has disappeared from the shelves of amateur gardeners.

"Weed-lovers offer no credible solution to the problems their intransigence begets. They learn, instead, to make a virtue out of their own laziness."

It was with Basta and Simazine, when I was young, that I was able to garden on a large scale, turning over old soil with no fear of the rash of weed seedlings that my actions might otherwise bring to life.

Weed-lovers offer no credible solution to the problems their intransigence begets. They learn, instead, to make a virtue out of their own laziness. They re-brand weeds as ‘wildflowers’. Saying you use weedkillers is as bad as admitting that you enjoy hunting or shooting. It brings on the hate mail from the Plant Welfare Trust. What a beastly polarised society we live in.

It all comes back to what we hope to achieve by gardening. I see no point in tolerating native plants that will overrun the prettier ones that I wish to cultivate. If I put together a plant combination that creates agreeable harmonies or contrasts, I don’t want it messed up by inappropriate, Jack-the-lad volunteers. Yes, a field of buttercups is pretty, but let’s keep them out of the garden.

Charles Quest-Ritson is the author of the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses.

Alan Titchmarsh: The weeds I welcome with open arms

Our columnist Alan Titchmarsh used to spend hours ridding his garden of anything he hadn't planted himself. These days he

Credit: Alamy

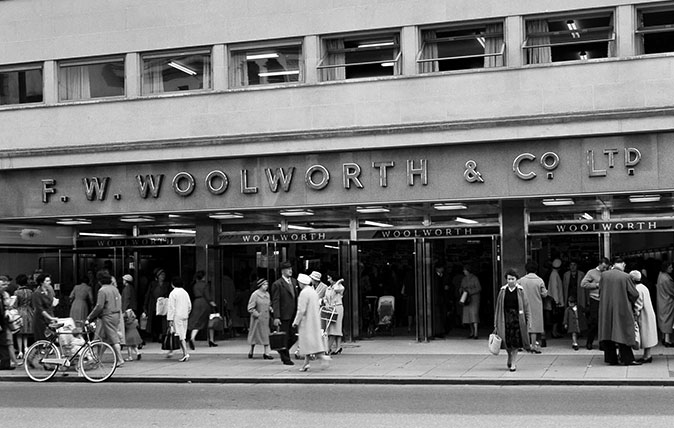

The day that Woolworths accidentally sold me an endangered species

Charles Quest-Ritson reminisces about the day his bargain purchase of a cyclamen in Woolworths proved to be something rather special.

Ultimate guide to growing roses: What to plant, where to plant it, and why you really don’t need to prune

Charles Quest-Ritson, author of the RHS Encylcopedia of Roses, tells you everything you need to know about growing roses.

Curious Questions: Why is there no such thing as a truly blue rose? And will we ever have one?

Breeding a blue rose has long been the Holy Grail for plant breeders everywhere. Charles Quest-Ritson, author of the RHS

David Austin, Britain's late, great king of roses: The man who brought about 'a revolution in taste, expectations and how we garden'

Charles Quest-Ritson pays tribute to David Austin, the rose breeder and entrepreneur who passed away at the end of last

The worst garden pests of all? The ones you invite in with open arms

A couple of weeks ago, Alan Titchmarsh wrote a lovely piece for Country Life about how to get children and

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-in-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.