The daftest plant name in English, and how it belongs to a wonderful flower just starting to show its potential

There are a lot of silly names for flowers our there – and Charles Quest-Ritson has a chilling warning for those who use the daftest of the lot.

Of all the ludicrous names that people give to plants, surely the silliest is ‘toadflax’.

Some people will suggest that no description could be more appropriate: its flowers resemble a toad’s face and its leaves a plant of flax. And it’s an old English word, whereas Linaria was concocted by the botanist Philip Miller in 1768.

Our native yellow toadflax is Linaria vulgaris, but what common name would anyone give to Linaria kulabensis from Tajikistan or the endangered L. tonzigii from Italy? It’s best to use Linnaean Latin; over-fanciful names are fatuous and unhelpful.

I make an exception for ‘foxgloves’. I am not the most herbaceous of gardeners, but I have never been without foxgloves or linarias. They are the happiest and most promiscuous of seeders. They pass from person to person in the potfuls of other plants that we give and receive.

Two years later, they rampage all over the garden. Beautiful and unfussy, I love them both, and each combines perfectly with shrubs that flower in early summer.

Foxgloves have been developed by gardeners and seedsmen for many years, so that it is now impossible to know all the available hybrids, selections and seedstrains or to make an informed choice about which to add to the garden.

But linarias have only just begun to show what they can do for us and, since their wild progenitors are very variable, the possibilities for future development are enormous. Their flowers are shaped like snapdragons, the lips of which (upper and lower) are often of different colour. They have long spurs and a conspicuous yellow or orange blob on the lower petals that serves as a landing pad for pollinating insects.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

"In my senility, I shall turn to short-lived linarias, hunting down as many species as I can find and scattering their seeds on a bed of gravel. The bumblebees will do the rest."

Best known is Linaria purpurea, a Mediterranean plant whose slender upright stems wave in the wind and bend whenever greedy bumblebees alight on the flowers. The species has rich purple flowers, but there’s a pink form called Canon Went that is even more popular, as well as a white one that is less exciting than the coloured types.

Established plants start into flower in early May and continue well into July. Then, in August, this year’s seedlings put out their first flowers and extend the display into autumn. And they seed themselves everywhere, not just in the driveway gravel (where I welcome them), but all through my flower beds.

Some years ago I came across another linaria called L. repens when driving the Route des Crêtes in Alsace, though it is actually a British native too. I took some seed, which germinated cheerfully and soon established itself in my garden as heartily as its big brother L. purpurea.

Despite its name, L. repens is not really a creeper – the plant has a more delicate, rounded shape – but its flowers are a good contrast to L. purpurea, because they are pale sky-blue with darker stripes. The bumblebees liked it too and, within a couple of years, some very pretty hybrids between the two species began to turn up.

It was at this point that I realised that the genus was just longing for meaningful relationships to develop among all its constituent species. I knew our native L. vulgaris, of course – its large yellow flowers are often to be seen on southern downlands – and I also grew two forms of L. triornithophora (one pink, one purple) the flowers of which are even larger, though the plant is, alas, slightly tender.

I also admired a wonderful montane species called L. alpina – a pale purple rock-plant with prominent yellow splashes on its lower lip – and dainty endemic species from Spain and North Africa.

It’s time to get going with the bumblebees. When I was young, with years ahead of me, I bred new cherries and magnolias, happy to wait 20 years for my seedlings to flower (most delivered in fewer than 10).

In middle age, I changed to hybridising roses, which need about four years to demonstrate what their seedlings promise.

In my senility, I shall turn to short-lived linarias, hunting down as many species as I can find and scattering their seeds on a bed of gravel. The bumblebees will do the rest for me.

Perhaps, in the distant future, there will be as many strains of linaria as there are of foxgloves. Think of me if you see packets with names like Beauty of Hampshire or Itchen Glory.

But I warn you… I shall come back and haunt the fatuous gardeners who call them toadflaxes.

The worst garden pests of all? The ones you invite in with open arms

A couple of weeks ago, Alan Titchmarsh wrote a lovely piece for Country Life about how to get children and

Things to know about insects, pollinators and predators

How to encourage good insects, the top pollinators and worst predators – all you need to know about insects, good

HRH The Prince of Wales: Why we must save our trees

In his birthday message to the countryside, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales urges us all to work together

The autumnal fruit that makes a questionable home-made liqueur

Charles Quest-Ritson explores the sorb apple, an astringent fruit added to apples to make a particular variant of cider.

Credit: Alamy

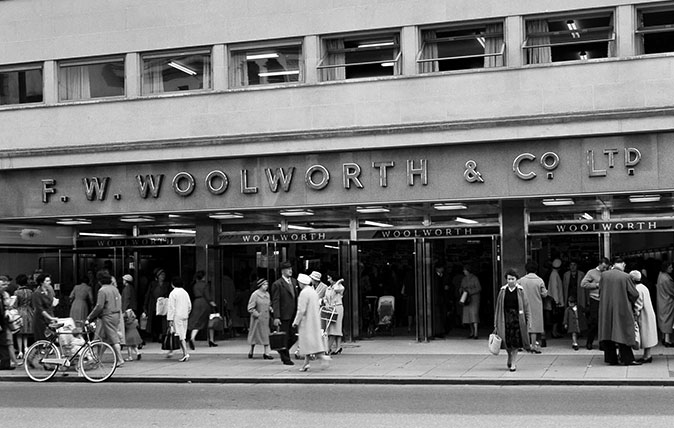

The day that Woolworths accidentally sold me an endangered species

Charles Quest-Ritson reminisces about the day his bargain purchase of a cyclamen in Woolworths proved to be something rather special.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published