Curious Questions: What is the biggest potato ever grown?

As harvests come in across Britain, we always enjoy pictures of giant vegetables appearing at various shows. But the tale of the biggest of the lot is absolutely fascinating. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions', investigates.

The short answer is simple: it was 8lb 7oz, and grown by Peter Glazebrook from Northamptonshire in 2010.

The long answer, however, is absolutely fascinating – and involved an international hoax that still resonates today, and which involves an early (albeit far from the first) tale of 'Photoshopping' a picture.

There are three main protagonists in our story; a potato grower named Joseph Swan, the editor of the Loveland Reporter, one W L Thorndyke, and Adam Talbot, a photographer.

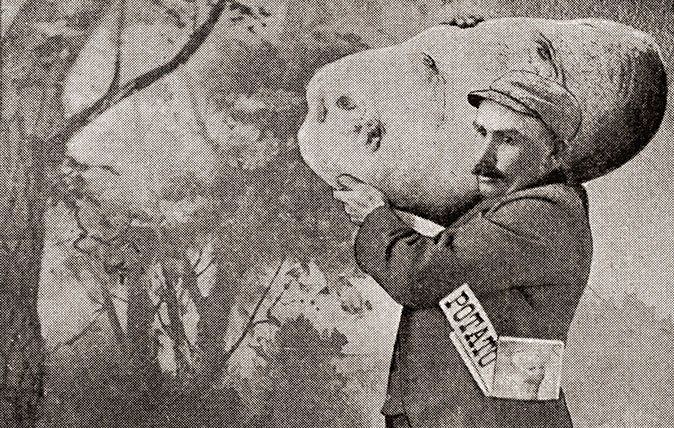

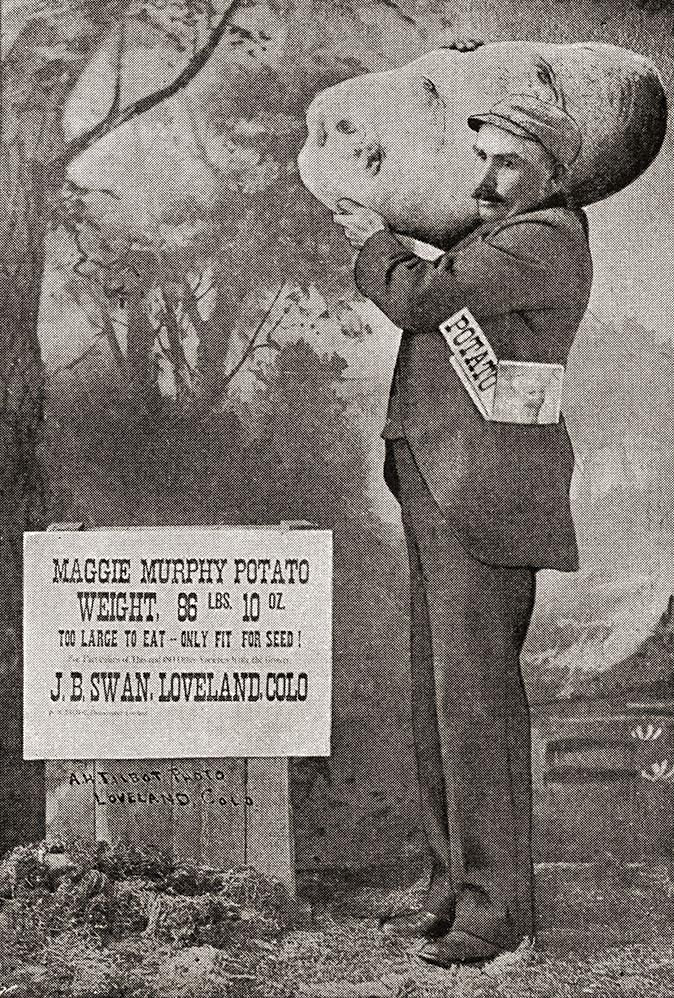

Swan was very proud of his spuds, claiming to have grown 26,000 pounds of the tuberous crop in one year on a single acre of land on his farm just outside the Colorado town of Loveland. The Loveland street fair was on the horizon and Thorndyke suggested that the farmer should indulge in a spot of advertising to boost the sale of his crops. His idea was to create a photograph featuring Swan proudly bearing a massive potato. The resulting image could be used as a flyer to promote Swan’s wares.

Thorndyke enlisted the services of Talbot who, considering he had neither a computer nor any clever software, showed considerable ingenuity in creating the required photo. He took a picture of a spud, blew it up as large as the limits of the then technology allowed him, stuck the image on to a board which he had cut out and then got the smiling Swan to pose with the giant potato on his shoulder.

"The original story spread like wildfire nationally and internationally and Swan was inundated with requests to see the spud"

The image seemed to do the trick, causing mirth and merriment amongst the locals, many of whom requested copies. All was well until in 1895 a picture got into the hands of a New Yorker called Dumont Clarke, who impressed by the inscription on the back stating that the potato was 28 inches in length by 14 inches wide and had been exhibited in the offices of the Loveland Reporter, passed it on to the Scientific American magazine.

Editorial standards must not have been very robust at the time as the Scientific American published it as a news item with an impressive engraving of said spud on 18th September 1895. They soon realised that the photo was a fake and printed an angry retraction; ‘the photo…proves to be a gross fraud, being a contrivance of the photographer who imposed upon us as well as others. An artist who lends himself to such methods of deception may be ranked as a thoroughbred knave, to be shunned by everybody.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

But the genie was out of the bottle. The original story spread like wildfire nationally and internationally and Swan was inundated with requests to see the spud or to have some seeds from the plant so that they could grow their own mammoth potato. Swan grew tired of explaining that it was a hoax which had got out of hand, resorting in the end to saying that it had been stolen.

The story did the rounds again, when it was featured, with the original photograph, in the London magazine, the Strand Magazine. They too printed a retraction but it still reappears every now and again to this day.

Whether Talbot’s photograph isn't the first example of a doctored image – artists and photography pioneers had been making cameras lie for decades – but it was certainly the first to gain international traction and helped inspire all sorts of imitators. With the cost of photography tumbling there was a fashion amongst photographers to create images, reproduced as postcards of impossibly large farm and dairy products. They proved immensely popular. Whether Talbot was tapping into this trend or was the forerunner is unclear. It was a remarkable feat, however you look at it.

As for the real record holder, Mr Glazebrook? His potato is all well and good, but wait until you see his onion... and his marrow, and his cauliflower, and his carrot...

Martin Fone is author of ‘Fifty Curious Questions’ – find out more about his book or you can order a copy via Amazon.

Curious Questions: Do love potions actually work?

The idea of a potion that can make someone fall in love is as old as the idea of love

Curious Questions: How do you make the perfect cream scone?

Credit: apples and oranges Photo by Best Shot Factory/REX/Shutterstock

Curious Questions: Can you actually compare apples and oranges?

It's repeated so often these days that we've come to regard it as a truism, but are apples and oranges

Curious Questions: Why do the British drive on the left?

The rest of Europe drives on the right, so why do the British drive on the left? Martin Fone, author

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham Dockyards

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham DockyardsAn antique dealer with an eye for colour has rescued an 18th-century house from years of neglect with the help of the team at Mylands.

By Arabella Youens

-

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in Kent

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in KentNorth Lodge near Tonbridge may seem relatively simple, but there is a lot more than what meets the eye.

By James Fisher

-

Curious Questions: How did the Leyland Cypress go from botanical accident to taking over the world?

Curious Questions: How did the Leyland Cypress go from botanical accident to taking over the world?The near-ubiquitous Leyland Cypress — or leylandii — is an evergreen with an extraordinary back story. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why do leaves change colour in Autumn? And why do some go yellow while others are red, purple or brown?

Curious Questions: Why do leaves change colour in Autumn? And why do some go yellow while others are red, purple or brown?The riotous colours on the trees around us are one of the highlights of the year — but why do leaves change colour in Autuumn? Mark Griffiths explains.

By Mark Griffiths

-

Curious Questions: What is a garden hermit?

Curious Questions: What is a garden hermit?Martin Fone takes a look at the curious history of the hermits who spent years living happily in the grounds of country houses, perhaps the ultimate garden folly.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Will the aspidistra ever fly again?

Curious Questions: Will the aspidistra ever fly again?The aspidistra was once the most popular of all houseplants in Britain, but these days they're barely seen. Why did that happen, asks Martin Fone, and can it make a comeback?

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: How did garden gnomes take over the world — and even The Queen's private garden?

Curious Questions: How did garden gnomes take over the world — and even The Queen's private garden?Vertically challenged, bearded and rosy-cheeked, cheerful gnomes might make for unlikely cover stars, but — says Ben Lerwill — they’ve long graced books, album covers and even The Queen’s private garden.

By Ben Lerwill

-

Curious Questions: How do you tell the difference between a British bluebell and a Spanish bluebell?

Curious Questions: How do you tell the difference between a British bluebell and a Spanish bluebell?Martin Fone delves into the beautiful bluebell, one of the great sights of Spring.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What's the difference between a labyrinth and a maze?

Curious Questions: What's the difference between a labyrinth and a maze?You may never have thought to ponder what distinguishes a labyrinth from a maze. But as Martin Fone explains, it's something of a minefield.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Which came first — the plastic flower pot or the garden centre?

Curious Questions: Which came first — the plastic flower pot or the garden centre?Martin Fone takes a look at the curiously intriguing tale of the evolution of nurseries in Britain.

By Martin Fone