Climate change fatigue

Although some ideas about what one does and does not spray on the garden may be out of date, a 70 year old book still contains many pearls of wisdom.

I Wonderif it is permissible to confess to a dose of climate change fatigue? Global warming may still be a new toy for media pundits and politicians to juggle with, but English gardeners have been gossiping among themselves about out of season burgeonings and blossomings for at least two decades (and, of course, being English, we never tire of the subject of the weather).

One result is that our tried and trusted gardening manuals of old have now been deemed out of date and no longer fit for our shelves, by the RHS among others. But are they? I have been thumbing through Arthur Hellyer's Your Garden Week by Week (first published in 1936 with subsequent editions, the fourth dating from 1977). A bible for the conscientiously productive gardener, with its endless sowings, lime washings, budding, disbudding, pricking out, potting on, bedding down, standing out, double digging and sterilising, it admonishes those of us who only manage to slot in a few hours here and there between the main business of earning a living. It is invaluable, all the same, as it describes in no-nonsense, prescriptive style everything that you could possibly imagine doing in garden and greenhouse, any day of the year (and it certainly has no time for wasteful things like holidays).

Of course, much of it is terribly out of date, particularly regarding spraying and chemicals. The substances it recommends have long been banned or replaced by more sophisticated, less dangerous versions. Mr Hellyer, a prolific and highly respected writer (and for many years a regular contributor to Country Life), was of the pre-Second World War generation excited by the dawn of a chemical age, and brought up to reach for pesticides as the first line of defence. Integrated management using natural predators for pest control and, indeed, organic gardening, were certainly not part of his repertoire. Garden styles and plant fashions have also changed enormously in the past 30 years, and plenty of the greenhouse and conservatory species nurtured in Mr Hellyer's handy volume are now proving to be hardy outdoors all year.

But there is still much in Your Garden Week by Week that is pertinent. Take lawns, for example. 'There is a widespread belief that the mowing machine should be put away during the winter, but this is entirely erroneous,' says Mr Hellyer. 'Occasional winter mowing keeps the lawn neat and prevents deterioration of the sward.' Quite so. And we shouldn't forget that many of the gardener's tasks connected with planting, sowing and pruning have more to do with seasonal light levels than actual temperatures, which climate change is unlikely to alter.

Ignore the awful substances Mr Hellyer recommended in sprays, dusts, powders and smokes; forget the arcane pruning methods for roses, now recognised (by the Royal National Rose Society) as less helpful to roses than shearing over them with a hedgetrimmer. Your Garden is still as good a place as any for practical instruction on taking cuttings, making your own potting composts, managing the vinery, the cold frames even the old-fashioned rock garden. And, not least, for dreaming of what you could be doing were you not far too busy getting on with life.

One plant that does not feature in Mr Hellyer's tome is the pomegranate, although I predict that we will be seeing much more of it in gardens soon. Pomegranates are all the rage as a 'superfood', having diverse properties including countering the effects of cholesterol and heart disease. Its health giving powers were well known to ancient civilisations, which revered it, and its composition a large berry filled with flesh encased seeds naturally made it a fertility symbol throughout the ancient world.

It had not occurred to me that pomegranates could set fruit outdoors in British gardens until I saw them last autumn in East Anglia, on a bushy tree spangled with rosy fruits, resembling Christmas baubles. Most were not much larger than golf balls, but who knows? Pomegranates sold in the UK are chiefly bred for their startling scarlet (or in some cases, yellow) flowers. My search is now on, not simply for any old pomegranate, but one that has the potential to make good-sized, palatable fruit, here, in our climate changed English garden.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

George Monbiot: 'Farmers need stability and security... Instead, they're contending with chaos'

George Monbiot: 'Farmers need stability and security... Instead, they're contending with chaos'The writer, journalist and campaigner George Monbiot joins the Country Life podcast.

By Toby Keel

-

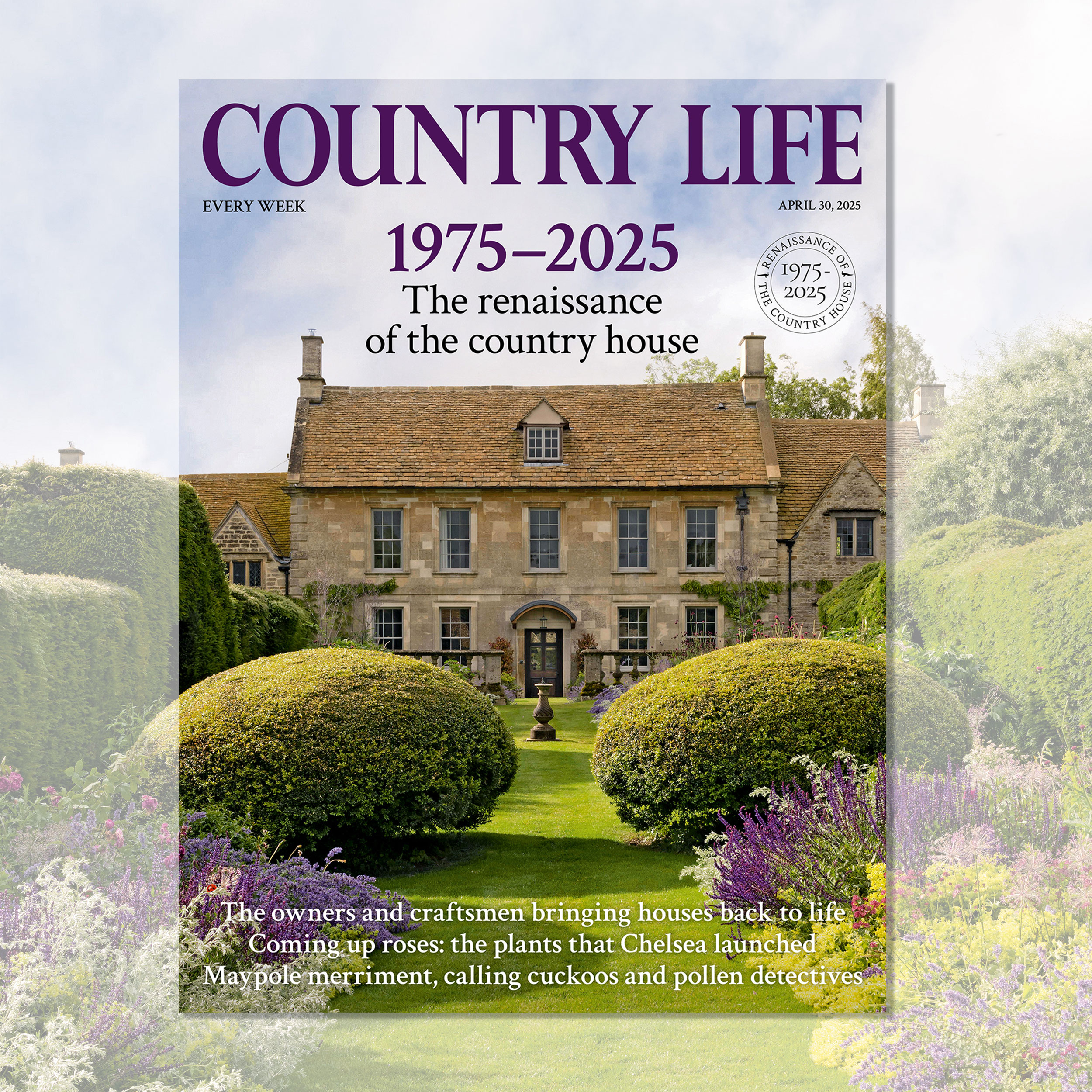

Country Life 30 April 2025

Country Life 30 April 2025Country Life 30 April 2025 is a glorious celebration of the country house in Britain, and the tale of its renaissance in the last fifty years.

By Country Life