Charles Quest-Ritson: Winter buddlejas, and the plant that might just cover the VAT on your children's school fees

Charles Quest-Ritson on the buddlejas that help see him through the winter — and the plant breeding idea that could help you grow a small fortune.

In October, a gardener’s fancy turns to… devising a survival strategy to get himself through the winter ahead. I have never shared my wife’s great love for all that mist and mellow fruitfulness. Autumn colour brings the promise of six months of cold, miserable weather. The days get shorter and darker and none of my favourite flowers is in action.

The best way to get through the gloom is to escape to a warmer climate, rather as our rich ancestors did 100 years ago. Most of them took le train bleu to the Riviera, but some more adventurous sparks overwintered in Malta or North Africa. My great-grandfather sailed off to Madeira, where his youngest son, deemed to be delicate, told me he spent the happiest days of his childhood. He remembered croaking bullfrogs, fruit-laden palm trees, scarlet hibiscus and sneeze-making mimosas, but the plant that most impressed me when I first went to Reid’s Hotel in 1980 was an orange buddleja.

Buddlejas are summer-flowering plants and most of them are purple. That, at least, was my conviction. I had grown a white form of Buddleja davidii and I quite liked B. globosa, the flowers of which come in little orange balls in summer. However, the plant I saw in Madeira had long, tapering spikes of richly orange, honey-scented flowers in January. I wondered whether it was hardy in England and concluded that it wasn’t — otherwise, I would have seen it. I had recently built a large conservatory, so a cutting from Reid’s duly found its way home with me. Its name, I discovered, was B. madagascariensis, which confirmed that it needed TLC to get through an English winter.

It quickly grew to cover the roof of my conservatory with flowers that started before Christmas and continued right to the end of April. I told myself that, one day, when I could find the time, I would cross it with Buddleja davidii to obtain hardy winter-flowering buddlejas. Whatever their colour, the flowers would cheer us up at the gloomiest time of the year. They would be a real advance on what was available for our gardens in winter.

"As with so many plants from a Mediterranean climate, English damp is the enemy, not the cold"

I then discovered there were other winter-flowering buddlejas. A fine specimen of B. asiatica grew in one of the conservatories at Wisley in Surrey (it’s embarrassing to remember how many plants have disappeared from the RHS’s care over the years). The Asian buddleja is an elegant small tree with pendulous branches and long, white flower spikes, as honey-scented as any other species. There is a hybrid between it and B. madagascariensis called ‘Margaret Pike’, which I also grew for a while, but it is not as good as either of its parents.

When winter moves towards spring, a range of little-known buddlejas bursts into flower. Some of them are hardy against a wall in much of England. Buddleja auriculata is a most useful species from the Western Cape, with small buff-coloured flowers in fair-sized panicles, usually in full flower by December. B. officinalis follows, coming into flower before Christmas and blooming well into March. Its soft mauve flowers are set off by large grey leaves with woolly white undersides.

Both species will grow to 6ft and have that heavy, sweet scent of honey that is so attractive. Both are available from English nurseries and will perform even better in the shelter of a cold greenhouse or conservatory. They are easy to propagate from cuttings and not fussy about the type of soil, provided it has good drainage — chalk and sand are, therefore, better than heavy clay. As with so many plants from a Mediterranean climate, English damp is the enemy, not the cold of our winters.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The best place to see buddlejas in Britain is Longstock in Hampshire, but these are summer-flowering forms and hybrids, laid out in long, grass-edged borders where you can walk up and down the lines picking out the names of cultivars that take your fancy. Gardeners will tell you that climate change has its upside, but I know of no English garden, as yet, where you will find all the winter-flowering species. For that, you must still travel down to the Riviera.

I never did get round to crossing Buddleja madagascariensis with B. davidii, the promiscuous thug that you see in railway sidings all over England. It would have been a fine endeavour — and might even have made me a fortune. I thus offer you the possibility. You would find a great range of colours turned up if you chose a dark form, such as ‘Black Knight’, to work with and, although making a fortune may be an exaggeration, your best seedlings might help to pay the VAT on your children’s or grandchildren’s school fees.

Charles Quest Ritson is the author of the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses

Credit: Clive Nichols

Charles Quest-Ritson: 'Gardens of supreme botanical importance are being degraded by new owners and changing priorities'

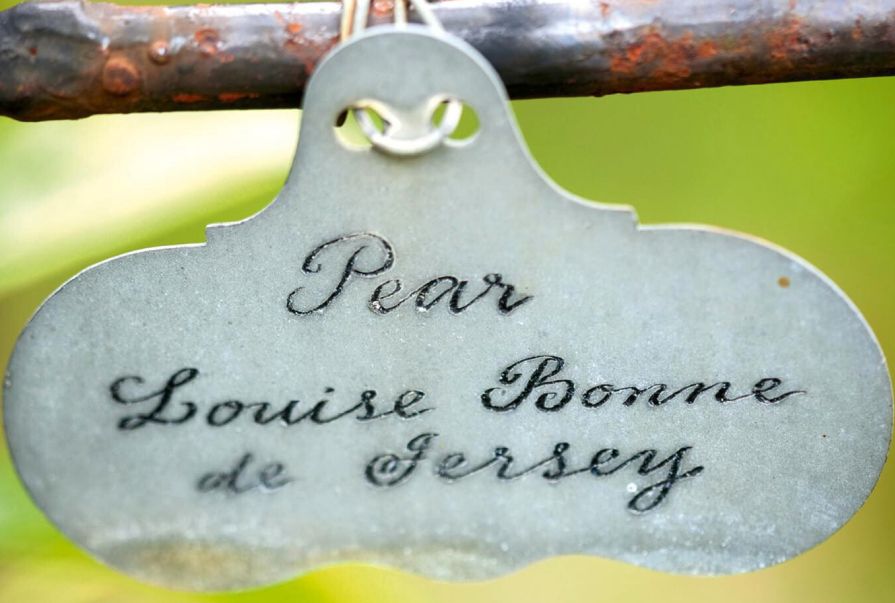

What's in a label? More than you might think, says Charles Quest-Ritson.

Credit: Getty Images

Charles Quest-Ritson: no chain, no gain — how using a chainsaw will improve your garden

Gardeners can be reluctant to take a blade to a healthy tree, but sometimes a severe pruning will leave both

Charles Quest-Ritson: The 'devastating consequences' when two of Britain's greatest-ever gardeners met for afternoon tea

A single meeting between Graham Stuart Thomas and Gertrude Jekyll shaped the career and thinking of the 'greatest gardener ever',

Credit: Getty Images

Charles Quest-Ritson: 'I'm always amazed by the codswallop that garden experts write'

Charles Quest-Ritson takes aim at some of the gardening advice that constantly does the rounds despite being complete nonsense.

Charles Quest-Ritson: I hate almost all alliums — their colour is hideous, their smell is disgusting — but there's one I've fallen hopelessly in love with

Charles Quest-Ritson loves almost all flowers. And the emphasis this week is very much on 'almost'.

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-in-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.